Whether you’ve volunteered to self-quarantine, or have done so from necessity, health experts worldwide say home is the best place to be right now to reduce the spread of COVID-19. For some this means layoffs, or remote assignments, or an anxious and indefinite staycation. For others it means a loss of safety or resources. No matter how much choice we had in the matter, there are those among us who harbor ambitious fantasies of using the time to finally finish labors of love, whether they be crochet, composing symphonies, or writing a contemporary novel about a plague.

Many lifesaving discoveries have been made in the wake of epidemics, and many a novel written, such as Albert Camus’ The Plague, composed three years after an outbreak of bubonic plague in Algeria. Offering even more of a challenge to housebound writers is the example of Shakespeare, who wrote some of his best works during outbreaks of plague in London, when “theaters were likely closed more often than they were open,” as Daniel Pollack-Pelzner writes at The Atlantic, and when it was alleged that “the cause of plagues are plays.”

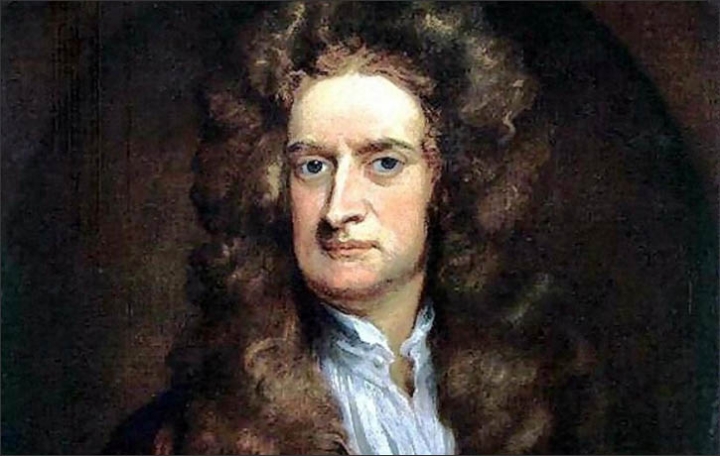

You can forgive yourself for taking a few days to organize your closets, or—let’s be real—binge on snacks and Netflix series. But if you’re still looking for a role model of productivity in a time of quarantine, you couldn’t aim higher than Isaac Newton. During the years 1665–67, the time of the Great Plague of London, Newton’s “genius was unleashed,” writes biographer Philip Steele. “The precious material that resulted was a new understanding of the world.”

In Shakespeare’s case, only decades earlier, the “plagues may have caused plays”—spurring poetry, fantasy, and the epic tragedies of King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. Newton too was apparently inspired by catastrophe.

These years of Newton’s life are sometimes known in Latin as anni mirabilies, meaning “marvelous years.” However, they occurred at the same time as two national disasters. In June 1665, the bubonic plague broke out in London…. As the plague spread out into the countryside, there was panic. Cambridge University was closed. By October, 70,000 people had died in the capital alone.

Newton left Cambridge for his home in Woolsthorpe. The following year, the Great Fire of London devastated the city. As horrifying as these events were for the thousands who lived through them, “some of those displaced by the epidemic,” writes Stephen Porter, “were able to put their enforced break from their normal routines to good effect.” But none more so than Newton, who “conducted experiments refracting light through a triangular prism and evolved the theory of colours, invented the differential and integral calculus, and conceived of the idea of universal gravitation, which he tested by calculating the motion of the moon around the earth.”

Right outside the window of Newton’s Woolsthorpe home? “There was an apple tree,” The Washington Post writes. “That apple tree.” The apple-to-the-head version of the story is “largely apocryphal,” but in his account, Newton’s assistant John Conduitt describes the idea occurring while Newton was “musing in a garden” and conceived of the falling apple as a memorable illustration. Newton did not have Netflix to distract him, nor continuous scrolling through Twitter or Facebook to freak him out. It’s also true he practiced “social distancing” most of his life, writing strange apocalyptic prophesies when he wasn’t laying the foundations for classical physics.

Maybe what Newton shows us is that it takes more than extended time off in a crisis to do great work—perhaps it also requires that we have discipline in our solitude, and an imagination that will not let us rest. Maybe we also need the leisure and the access to take pensive strolls around the garden, not something essential employees or parents of small children home from school may get to do. But those with more free time in this new age of isolation might find the changes forced on us by a pandemic actually do inspire the work that matters to them most.

Related Content:

In 1704, Isaac Newton Predicts the World Will End in 2060

Sir Isaac Newton’s Papers & Annotated Principia Go Digital

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness