“Kipling is in the peculiar position of having been a byword for fifty years,” writes George Orwell in a 1942 essay on the author of The Jungle Book and “Mandalay.” “During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there.” A similar truth holds for Fight Club, David Fincher’s film adaptation of the Chuck Palahniuk novel, which over the past twenty years to the day since its wide release has outlasted all the serious, intelligent, and indeed enlightened critiques mounted against it. Fight Club has long been a byword, if not since its financially disappointing run in the theaters, then at least since its deluxe DVD release. But what does that byword signify?

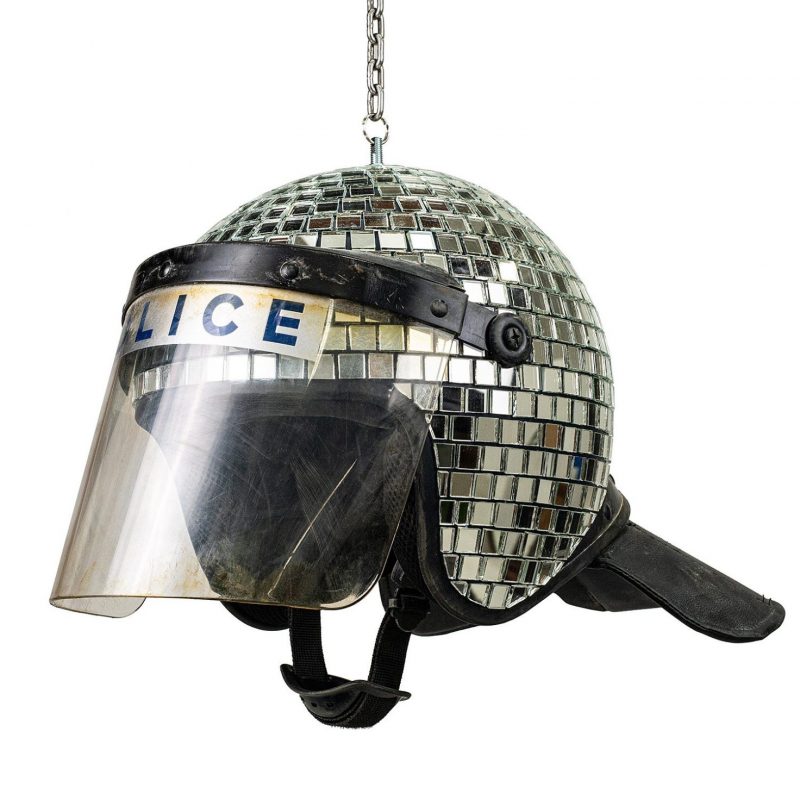

For many, it signifies the tastes and attitudes of a certain kind of twentysomething male — and given the unabated prevalence of Fight Club posters in freshman dorm rooms and fraternity houses, hardly without cause. At first glance, its subject matter also looks geared straight toward angry young men, telling as it does of a white-collar corporate drone who breaks out of his office dystopia by getting together with similarly alienated late-20th-century men and beating one another senseless. Before long, these “fight clubs” cohere into a nationwide terrorist organization bent on destroying consumer society. For some viewers, the movie would seem to have it all: violence, of course, but also sex, special effects, and satire aplenty, particularly at the icons of so-called “late capitalism.” (Legend has it that Fincher worked a Starbucks cup into nearly every scene.)

Other viewers argue — making what Orwell, writing on Kipling, calls a “shallow and familiar charge” — that Fight Club is “fascist.” They see it as glorifying the act of raising a shaven-headed, black-clad, repetitively chanting army under a charismatic leader, in this case a Nietzschean Übermensch by the name of Tyler Durden. Portrayed by Brad Pitt in perhaps the most memorable role of his career, Durden emerges from the mind of Fight Club’s nameless narrator (an increasingly pale and wasted Edward Norton) in order to set him on his journey. “He’s tried to do everything he was taught to do, tried to fit into the world by becoming the thing he isn’t,” Fincher has said of that narrator’s journey. “He cannot find happiness, so he travels on a path to enlightenment in which he must ‘kill’ his parents, god, and teacher.”

The narrator creates Tyler, his teacher, and “kills his god by doing things they are not supposed to do. To complete the process of maturing, the narrator has to kill his teacher.” Writing at philosophical subreddit The Motte, Redditor Dormn111 sums up Tyler’s worldview as follows: “Men are suffering today because they are inherently unsuited for the social demands of modernity.” Evolved to be “violent, aggressive, and driven by their very real biological urges,” men are now “told that these aspects of themselves are barbaric, evil, and worthy of condemnation.” There is no place in Francis Fukuyama’s post-struggle “end of history” for “the gut-level desires that men feel in their bones. There is no victory, no power, no dominance. Everything the man is supposed to do builds towards some sort of higher status, but the gains are illusory.”

Participation in a fight club is “an act of self-destruction to counter the societal obsession with self-improvement,” since it “makes men ugly, injured, tired, late for work, and shifts their priorities from the feminine social hierarchy treadmill to a narcotic-like rush of masculine gratification.” It gives them “a real sense of stakes in their lives, like the sort that mortal combat would have given them in the past.” In the words of the Wisecrack video on the philosophy of Fight Club at the top of the post, which draws on thinkers like Jacques Derrida, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer, these men rebel against a system that “favors efficiency over tradition, custom, or individual desires” and produces stultifying lives in which is everything is “designed for a specific purpose, mass-produced and unrelentingly predictable.”

The same creators break down the act of interpretation, using the tools of semiotics and pragmatism, in their video on the meaning of Fight Club and why we still can’t agree on it. Fans and detractors alike come to especially different conclusions about the film’s ending in which the narrator kills his teacher, a scene The Take attempts to explain in its own video essay. And despite being idea-driven, Fight Club also offers one of the more visceral viewing experiences (and for some, an entirely too-visceral viewing experience) in all of cinema, thanks not only to visuals that struggle against containment by the very medium of film, but also to the work of foley artists revealed in Film Radar’s video on the movie’s sound design — the craftsmen tasked with making the impact of a punch sound, unlike in most Hollywood pictures, as if it actually hurts.

Fight Club continues to make an impact of its own, as examined in the Fandor video just above. It names among the film’s lovers Quentin Tarantino and among its haters Paul Thomas Anderson, so whichever side you take on it, you’ll share an opinion with one of the most respected filmmakers alive today. But then, Fincher’s own auteur status should give pause to anyone who dismisses Fight Club out of hand. As the relevant chapter of Cameron Beyl’s Directors Series video essay tells it, making the movie was itself an act of rebellion against “the system,” specifically the studio system, and even more specifically 20th Century Fox, the studio that ruined his feature debut Alien 3 with its interference. After Fincher bounced back with hits Seven and The Game, Fox wanted him back to direct an adaptation of Palahniuk’s novel. Despite describing himself as a“non-reader,” Fincher devoured the book, which shared some of his own pet themes, including nihilism and anti-commercialism.

Fox, seeing the benefit in smoothing out their relationship with a filmmaker who showed signs of becoming a box office-friendly Alfred Hitchcock crossed with Stanley Kubrick, allowed Fincher a near-carte blanche, creatively speaking. “Once Fincher knew how to play his meddlesome executives to his benefit,” Beyl says, “he became truly unstoppable.” Fincher and his collaborators, most notably screenwriter Jim Uhls, didn’t make the kind of radical changes to Palahniuk’s novel that film adaptations usually do to their source material. The CineFix video below goes point-by-point through all the differences between book and film, many of which have to to with the character of Tyler Durden: the book presents him as more of a psychotic killer, while the film presents him as a kind of an idealist: down-and-dirty yet high-minded.

But does it also make him too handsome, too cool, too quotable? No examination of Fight Club, no matter how close, conclusively determines the film’s own position on Tyler or any other character, let alone its judgment of broad economic, political, and ideological concepts like capitalism and fascism (put on screen, in one of the film’s many ironies, by a former commercial director and a Hollywood heartthrob). “I love this idea that you can have fascism without offering any direction or solution,” Fincher once said. Fascism insists on going in one particular direction, “but this movie couldn’t be further from offering any kind of solution.” Fight Club endures because it resists straightforward interpretation, ensuring that disagreements about it will never be settled. And indeed, now that its themes happen to dovetail with so many of today’s vogue terms — “patriarchy,” “bro culture,” “toxic masculinity” — the arguments have grown more heated than ever.

Related Content:

How Did David Fincher Become the Kubrick of Our Time? A New, 3.5 Hour Series of Video Essays Explains

Why 1999 Was the Year of Dystopian Office Movies: What The Matrix, Fight Club, American Beauty, Office Space & Being John Malkovich Shared in Common

Watch Author Chuck Palahniuk Read Fight Club 4 Kids

The Truth Behind Jane Austen’s Fight Club: Female Prize Fights Were a Thing During the 18th Century

How Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner Illuminates the Central Problem of Modernity

Wes Anderson’s Breakthrough Film, Rushmore, Revisited in Five Video Essays: It Came Out 20 Years Ago Today

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.