Whether your New Year’s resolution involves taking up painting, managing stress, cultivating a more positive outlook, or building a business empire, the late television artist Bob Ross can help you stick it out.

Like Fred Rogers’ Mr Rogers’ Neighborhood, Ross’ long-running PBS show, The Joy of Painting, did not disappear from view following its creator’s demise. For over twenty years, new fans have continued to seek out the half-hour long instructional videos, along with its mesmerizingly mellow, easily spoofed host.

Now all 403 episodes have been made available for free on Ross’ official Youtube channel. That covers all 31 seasons.

It’s said that 90% of the regular viewers tuning in to watch Ross crank out his signature “wet-on-wet” landscapes never took up a brush, despite his belief that, with a bit of encouragement, anyone can paint.

Perhaps they preferred sad clowns or big-eyed children to scenic landscapes of the sort that would not have looked out of place in a 1970’s motel.… Or perhaps Ross, himself, was the big draw.

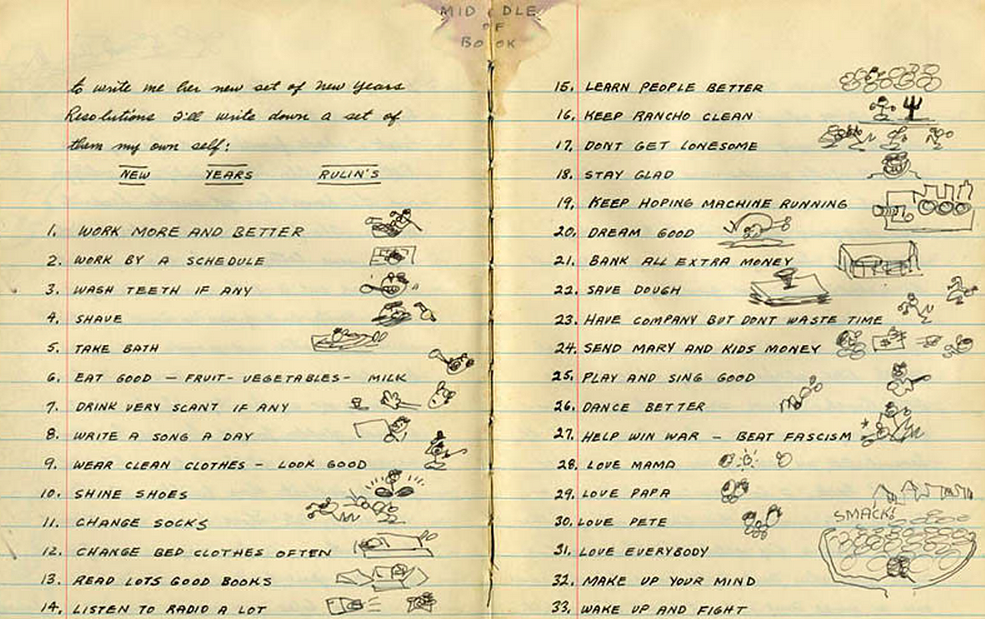

Like Mister Rogers, Ross spoke softly, using direct address to create an impression of intimacy between himself and the viewer. Twenty years in the military had soured him on barked-out, rigid instructions. Instead, Ross reassured less experienced painters that the 16th-century ”Alla Prima” technique he brought to the masses could never result in mistakes, only “happy accidents.” He was patient and kind and he didn’t take his own abilities too seriously, though he seemed like he would certainly have taken pleasure in yours.

Ross’ Land of Make Believe was a character-free natural world, in which many of the same elements appear over and over. According to Five Thirty Eight culture editor Walt Hickey’s statistical analysis, trees reigned supreme. The real life landscapes he observed as first sergeant of the U.S. Air Force Clinic at Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska became his lifelong subject, and by extension, that of untold numbers of home viewers.

His devotees may be content just seeing “happy little trees” and “pretty little mountains” bloom on canvas, but in an interview with NPR, Ross’ business partner, Annette Kowalski, suggests that he would not have been.

The gentle, forest-and-cloud-loving host was also an ambitious and highly focused businessman, who used TV as the medium for his success. Every folksy comment was rehearsed before filming and he stuck with the permed hairdo he loathed, rather than scrapping what had become a highly visual brand identifier.

Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Watch all 31 seasons of Bob Ross’ The Joy of Painting here, or right here on this page. Official Bob Ross painting kits are widely available online, or source your own using a cobbled together supply list.

Season Three

Season Four

Season Five

Season Six

We will continuing adding seasons to this list as they become available.

Season Seven

Season Eight

Season Nine

Season Ten

Season 11

Season 12

Season 13

Season 14

Season 15

Season 16

Season 17

Season 18

Season 19

Season 20

Season 21

Season 22

Season 23

Season 24

Season 25

Season 26

Season 27

Season 28

Season 29

Season 30

Season 31

Related Content:

Watch Bob Ross’ The Joy of Painting, Seasons 1–3, Free Online

Mr. Rogers Goes to Congress and Saves PBS: Heartwarming Video from 1969

Stream 23 Free Documentaries from PBS’ Award-Winning American Experience Series

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her resolution is to spend less time online, but you can still follow her @AyunHalliday.