Image by Thierry Erhmann via Wikimedia Commons

“This enormous novel we’re living inside thrives on sensation,” J.G. Ballard once said. “It needs sensation to sustain itself.” The author of novels like High-Rise, Crash, and Empire of the Sun knew how to deliver a certain kind of textual sensation, and he often underscored (as first evidenced by his experimental text collages) that he possessed a command of visual sensation as well. Ballard’s use of sonic sensation has taken longer to gain a wide appreciation, but the BBC has furthered that cause with two new radio dramas adapting his stories “Track 12” and “Venus Smiles.”

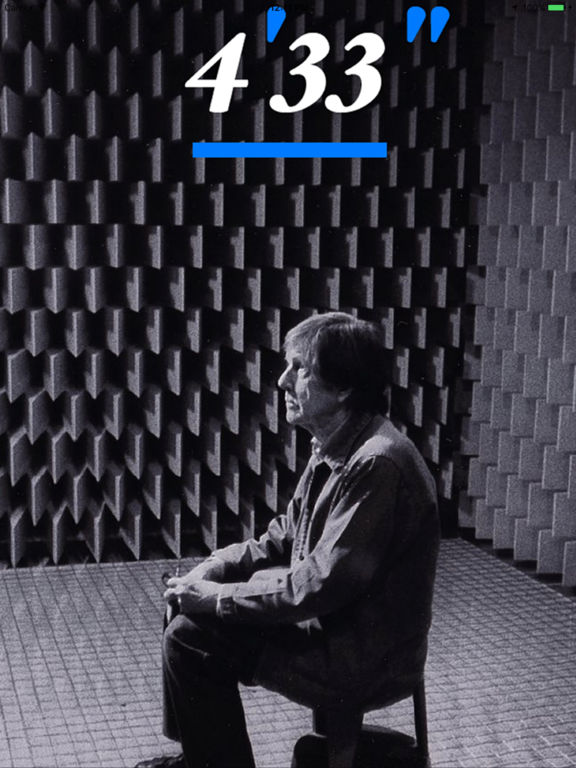

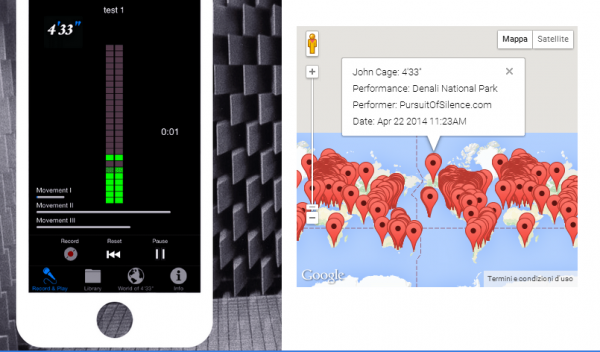

These productions debuted together this past weekend on “Between Ballard’s Ears,” an episode of the program Between the Ears, which for twenty years has showcased “innovative and thought-provoking features that make adventurous use of sound and explore a wide variety of subjects.” They both make use of a technology called binaural audio, sound recorded just as humans hear it. The process involves an artificial head with microphones embedded in each ear, the industry-standard model of which comes from a company called Neumann. (You can see a gallery of the cast and crew of “Between Ballard’s Ears” using, and hanging out with, their own Neumann head here.)

All this has the effect of putting you, the headphone-wearing radio-drama listener, right into not just the setting of the story but into the very head of the character — in the case of J.G. Ballard, as any of his fans know, a troubling place indeed. We hear 1958’s “Track 12” from within the head of Maxted, a former athlete turned company man invited over to the home of Sheringham, the biochemistry professor he’s been cuckolding. Sheringham sits Maxted, and us, down to listen to his greatly slowed and amplified “microsonic” recordings of cells dividing and pins dropping. We wonder, as Maxted wonders, when the inevitable confrontation will come, though none of us can foresee what form Sheringham’s revenge will take.

“Venus Smiles,” which Ballard first wrote in 1957 and rewrote in 1971, takes place in his fictional desert resort town of Vermillion Sands. This story opens with the installation of a new piece of public art, a “musical sculpture” that makes me think of the Triforium in Los Angeles. But unlike the lonely Triforium, neglected and ignored for most of its history, this sculpture causes pandemonium from day one, piping out quarter-tone compositions pleasing to the ears of the Middle East, but apparently not to those of Vermillion Sands. When one commissioner transplants the hated sculpture to his backyard, it reveals its true nature: much more complicated than that of a big music box, and much more interesting to hear besides. As much as the binaural production will make you feel like you’re standing right there beside it, Ballard makes you feel relieved, as the story goes on, that you’re actually not.

Related Content:

The Very First Film of J.G. Ballard’s Crash, Starring Ballard Himself (1971)

Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977)

J.G. Ballard’s Experimental Text Collages: His 1958 Foray into Avant-Garde Literature

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.