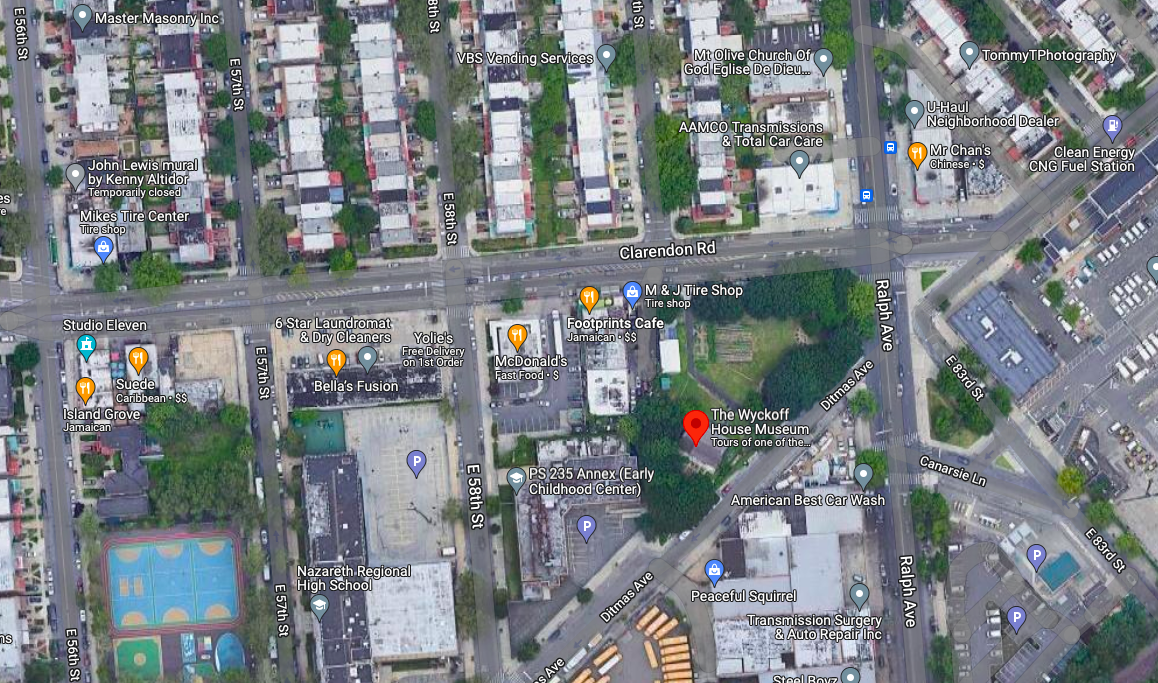

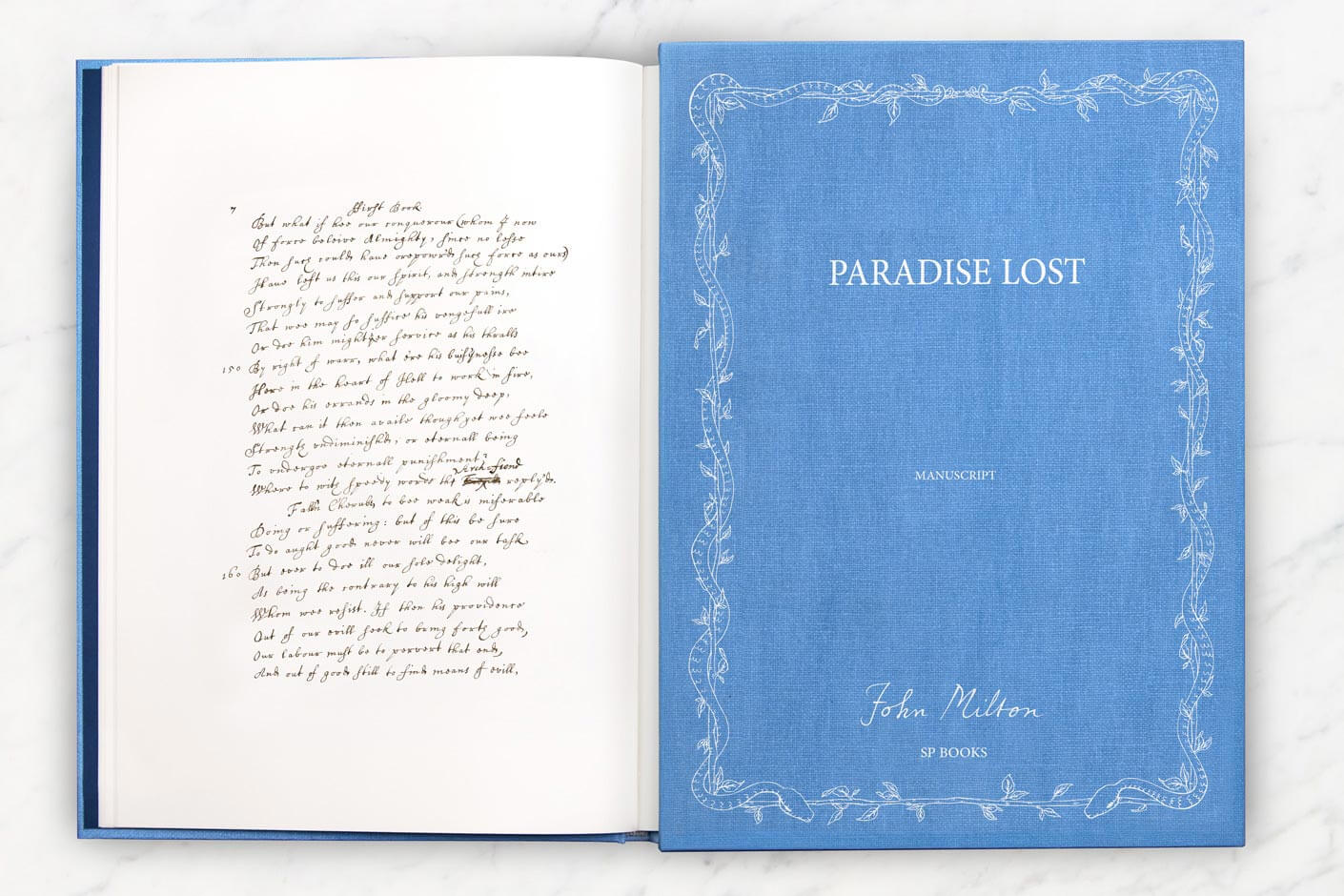

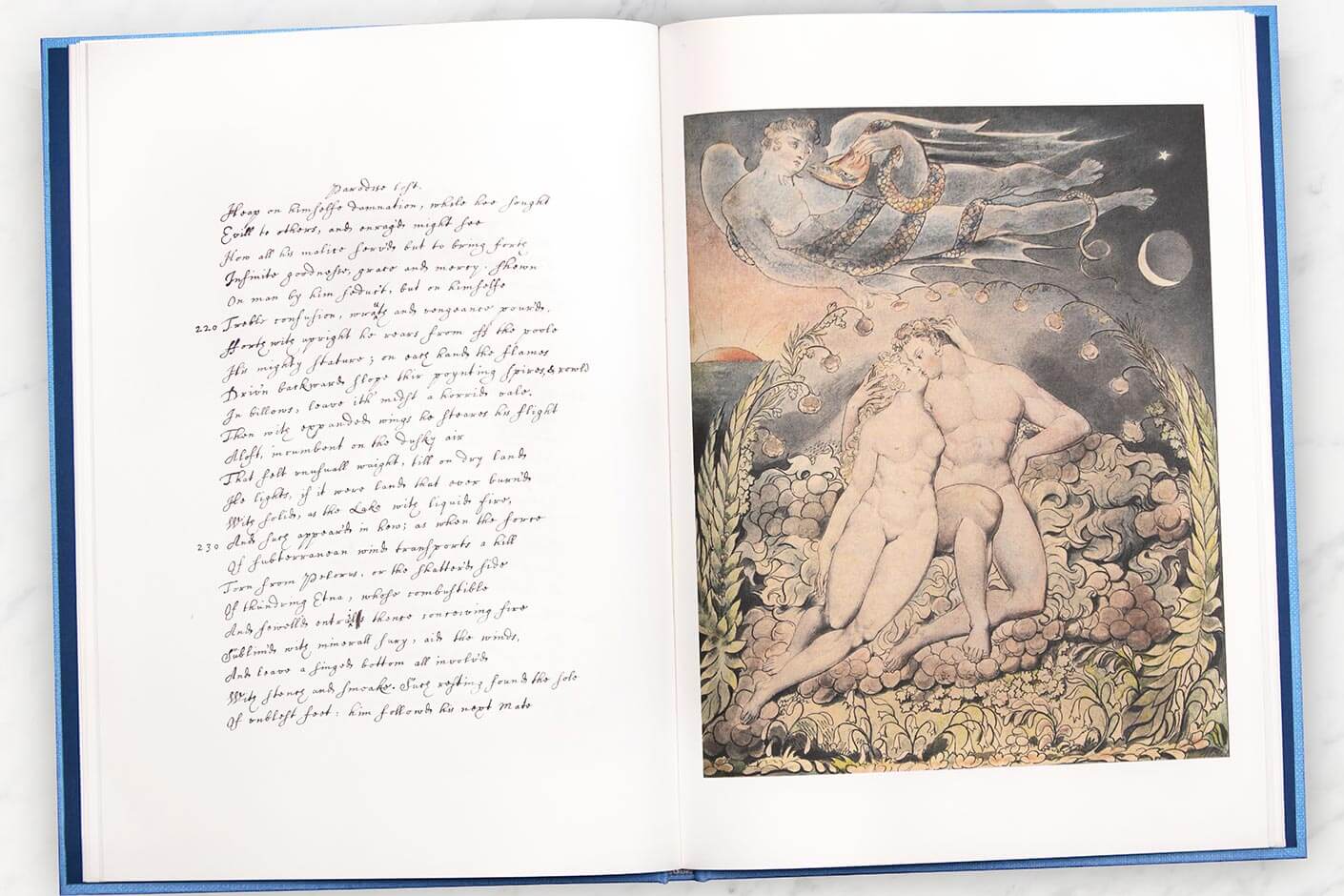

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake adds a note to the text that became a famous adage about John Milton’s Paradise Lost: the 10,000-line, 17th century blank verse epic about the war between heaven and hell and the failed testing of God’s premium product, human beings. Milton “wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when he wrote Devils & Hell,” Blake declared, “because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” The statement inspired “other Romantic and Gothic writers to view Satan as a hero,” the British Library writes.

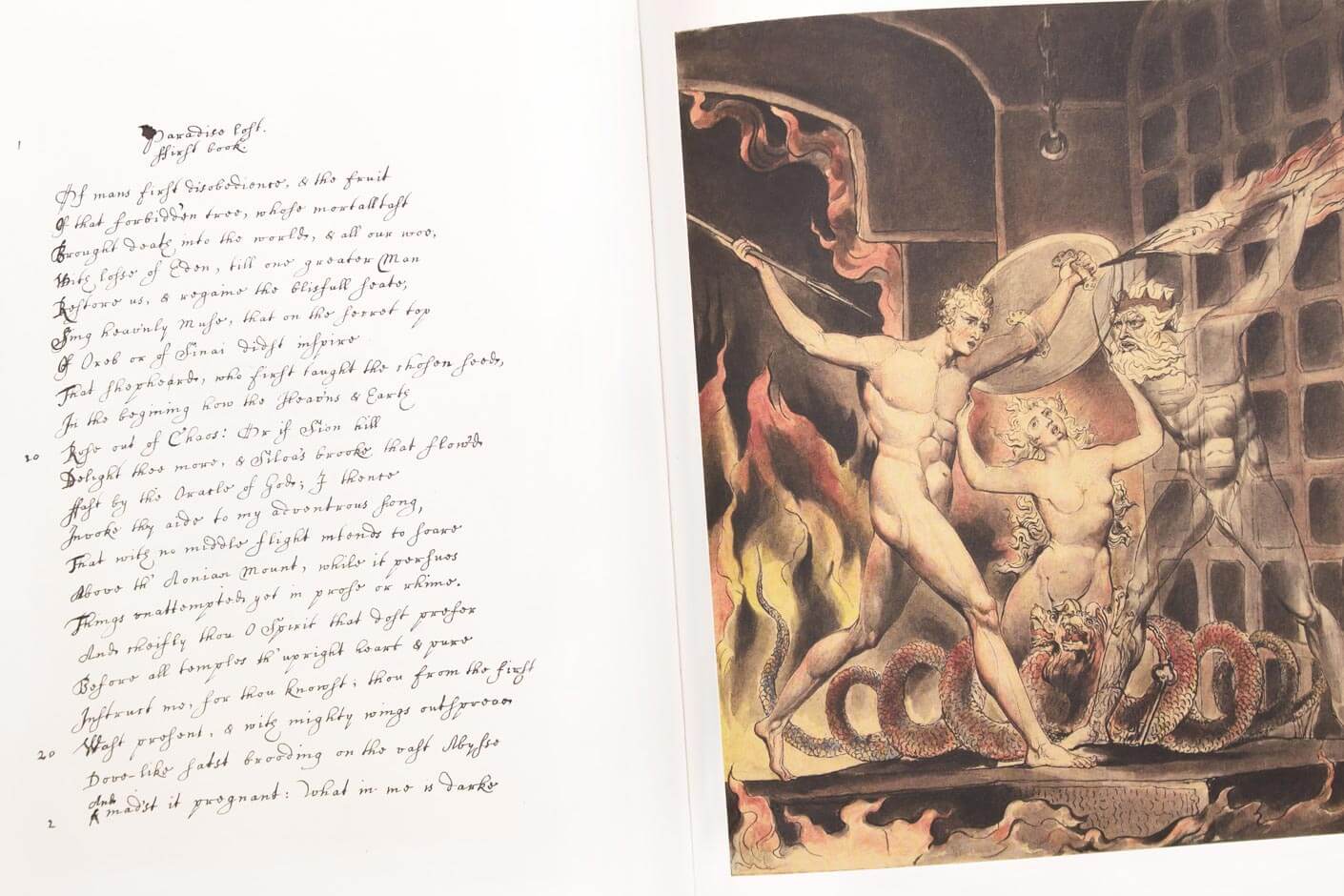

Blake himself illustrated Paradise Lost in three separate commissions over the course of his career as an engraver and printer. His deep admiration for the poem helped it become a “Bible of the Romantic movement,” writes the manuscript publisher SP Books in their introduction to a rare new book publication of the only surviving manuscript of the work.

Only 1,000 numbered, large format copies of this printing are available. (We do hope a subsequent edition will appear, maybe with a transcription and annotations. But it will not be as beautiful as this sky-blue cloth-covered book with Blake’s full-color illustrations.)

The book preserves the only part of the poem that survives in manuscript: 798 lines from Book One of Paradise Lost. These are not in Milton’s hand — he had been blind since 1652, and the poem was first published in 1667. He conceived the epic in his 50s, his career in government over after the English Civil Wars and the brief period of the Cromwells’ Protectorate ended in the Restoration of Charles II. “Milton composed ‘Paradise Lost’ aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) ‘leaning backwards obliquely in an easy chair,’ ” Lauren Christensen writes at The New York Times, “memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand.”

These first few hundred lines show why Satan seems so noble to Milton’s readers; speeches by and about him portray his doomed campaign as a righteous assault on heavenly tyranny. The Romantics’ use of Paradise Lost reflects their own preoccupations, while also echoing contemporary suspicions of the poem. “The authorities were concerned,” for example, Tom Paulin notes at The London Review of Books, by an image in Book One describing Satan:

as when the sun new ris’n

Looks through the horizontal misty air

Shorn of his beams, or from behind the moon

In dim eclipse disastrous twilight sheds

On half the nations, and with fear of changePerplexes monarchs.

“According to Milton’s early biographer, the Irish republican John Toland, Charles II’s Licenser for the Press regarded these lines as subversive,” Paulin points out, “and wanted to suppress the whole poem.” It’s surprising he was able to publish at all. Milton had vociferously supported the Puritan revolutionaries who overthrew the king’s father, Charles I, and removed his head. Milton later published several pamphlets in defense of regicide. In 1660, when Richard Cromwell’s Protectorate fell apart and Charles II returned, Milton’s works were banned by royal decree and the poet went into hiding until a general pardon.

Later critics have pointed to Milton’s political writings as evidence that he knew exactly whose party he was of. California State University’s Michael Bryson has gone so far as to argue that Milton was a secret atheist. In any case, he was a passionate believer in the overthrow of kings and the establishment of republics (for which he has become a libertarian hero). Paulin sums up the critical case for Paradise Lost as an allegory for the “lost cause” of the revolution:

Milton knew that the poem he was dictating to his amaneuensis would be scrutinized by the recently restored monarch’s Licenser of the Press, so he coded the English people’s formation of a republic as the creation of the “heavens and earth.” The idea passed the censor by, just as it has passed by many readers, but it was nonetheless Milton’s founding intention in composing his epic.

The charge that Milton made Satan a hero is hard to ignore when, reading Book One, we find the poet giving the Chief of Fallen Angels the best lines, as anyone who’s read Paradise Lost will remember. If you haven’t, just see the classic example below.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less than he

Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; th’Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence:

Here we may reign secure, and in my choice

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heav’n.

Learn more about this rare manuscript edition at The New York Times’ review and purchase one (if one remains) at SP Books.

Related Content:

The Otherworldly Art of William Blake: An Introduction to the Visionary Poet and Painter

Spenser and Milton (Free Course)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness