Image by Daniele Prati, via Flickr Commons

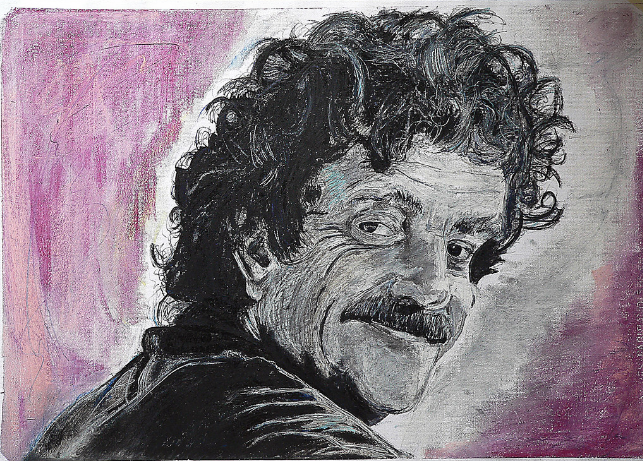

Kurt Vonnegut’s 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle resembles its title, a web of overlapping and entangled stories, all of which have huge holes in the middle. And the book—as have many of his slim, surrealist pop masterpieces—was read by many critics as lightweight—whimsical and sentimental. One reviewer in The New York Review of Books, for example, called Vonnegut a “compiler of easy to read truisms about society who allows everyone’s heart to be in the right place.”

Not so, argues University of Puerto Rico scholar Mark Wekander Voigt. For all its silliness—such as its Calypso-heavy “parody of a modern invented religion that will make everyone happy”—Cat’s Cradle, writes Voigt, “is essentially about the moral issues involved in a democratic government using the atom bomb.” Vonnegut’s novel suggests that “to be really ethical, to think about right and wrong, means that we must dispense with the authorities who tell us what is right and wrong.”

John, the hero of Cat’s Cradle, begins his absurdist hero’s quest by intending to write a “factual” accounting of what “important Americans had done on the day when the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan.” The references would not have been lost on Vonnegut’s contemporary readers, who would all have been familiar with John Hersey’s harrowing 1946 Hiroshima, the most popular book ever written about the dropping of the bomb, with six survivor’s stories told in a thrilling, engaging style and “all the entertainment of a well-written novel.”

Vonnegut, however, writes an alienating anti-novel, in part to demonstrate his point that “to discuss the ethical implications of dropping the bomb on Hiroshima, one should not look at the victims, but at those who were involved in developing such a bomb and their government.” Increasingly, however, it becomes harder and harder to look at anything directly. In the novel’s parody religion, Bokononism, all lies are potentially truths, all truths potentially lies. Language in the military-industrial-complex world of the bomb, Vonnegut suggests, had become as changeable and potentially deadly as the substance called “Ice‑9,” a polymorph of water that can instantly turn rivers, lakes, and even whole oceans into ice.

Evoking the novel’s high-wire balancing act of goofy songs and rituals and metaphors for the global annihilation of the earth by nuclear weapons, the 2001 album above, Ice‑9 Ballads, pairs Vonnegut with composer Dave Soldier and the Manhattan Chamber orchestra for an adaptation, of sorts, of Cat’s Cradle. Vonnegut narrates evocative snatches of the book, and the songs illustrate key themes, such as the strained patois the inhabitants of the fictional island of San Lorenzo speak. One example, the phrase “Dyot meet mat” (“God made mud”), gives us the title and refrain of the second track on the album.

“The music switches tones throughout to match the tone of the novel at some level,” writes Allmusic, and there are also two additional, vaguely-related pieces at the end. “A Soldier’s Story” is a “faux-radio opera,” notes Time Out New York’s Molly Sheridan, with a libretto, written by Vonnegut, about Eddie Slovik, the only soldier executed for desertion during World War II. A later 2005 release of “A Soldier’s Story” bore a Parental Advisory warning, though it is “not the obscenities that cause alarm, but the way in which moral contradictions inherent in the tale resonate against present-day military involvements.”

The final piece, “East St. Louis, 1968,” is a surprisingly experimental, orchestral-backed pastiche of soul, hip-hop and gospel. Truly, like many a Vonnegut novel, Ice‑9 Ballads, writes Allmusic, is “getting the avant-garde label from the eclecticism in it, but providing decidedly non-avant garde bits and pieces throughout that make the whole.… Don’t go in expecting something bland or predictable.” See more credits for the album at its label’s website here.

You can stream Ice‑9 Ballads on Spotify for free (get Spotify’s free software here) or purchase a copy online.

Related Content:

In 1988, Kurt Vonnegut Writes a Letter to People Living in 2088, Giving 7 Pieces of Advice

Benedict Cumberbatch Reads Kurt Vonnegut’s Incensed Letter to the High School That Burned Slaughterhouse-Five

Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.