When my son first started playing the piano, I lost several evenings chasing the holy grail of free online sheet music. Sadly, most of what we were interested in downloading wasn’t really free… just the first page.

It’s hard to rationalize dropping five bucks on one song, when the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts is a short subway ride away. The problem is, I’m not much of a musician, and while there are scores and scores of scores upon their shelves, I rarely understood what it was I was checking out. Often I’d come home with the sought after piece, only to realize that I’d inadvertently checked out a vocal selection, or the chord-rich equivalent of a cocktail pianist’s fake book.

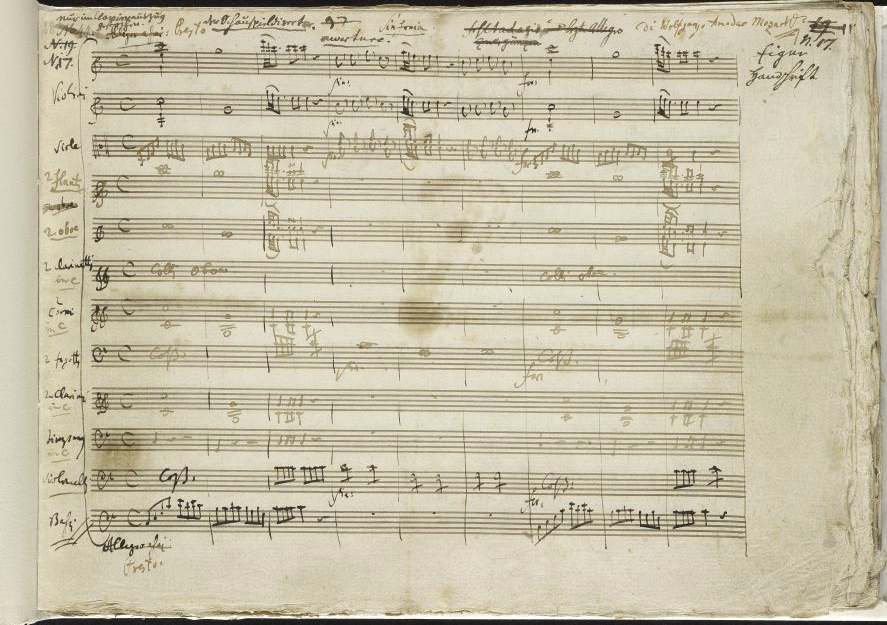

With the Morgan Library’s Music Manuscripts Online project, there’s no guarantee my son or I will be able to play it, but I do know exactly what I’m getting.

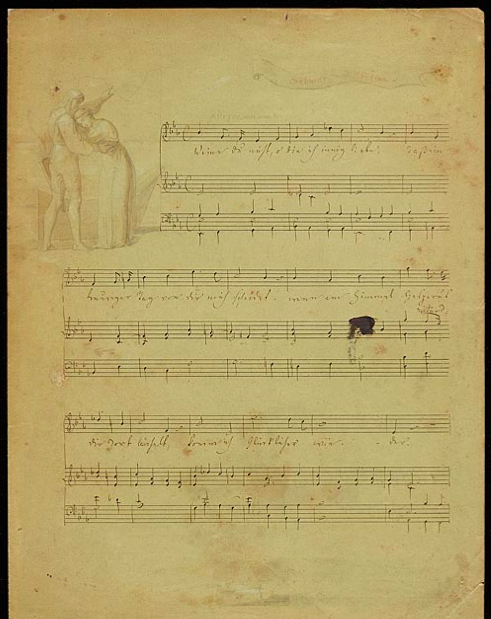

The handwritten manuscript of Mozart’s comic singspiel, Der Schauspieldirektor, above, for instance, autographed by the composer himself. 84 pages worth, not counting covers and endpapers, all free for the downloading!

Put that on your iPad, Mr. Salieri!

The collection currently offers digitized versions of upwards of 500 musical manuscripts, with more to come as the reviewing process continues.

It’s searchable by composer, and big names abound.

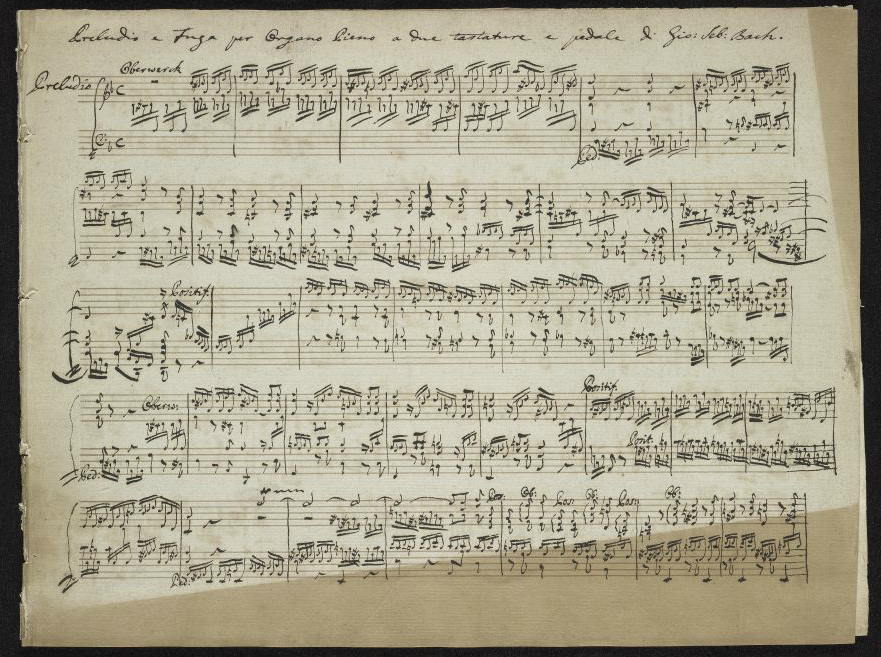

Perhaps you’d like to warm up the Wurltizer with Bach’s Toccata and Fugue for Organ, BWV 538, in D minor…

Or let all your opera singing, ballet dancing friends know you’re available to accompany them with Puccini’s autographed manuscript for Le Villi…

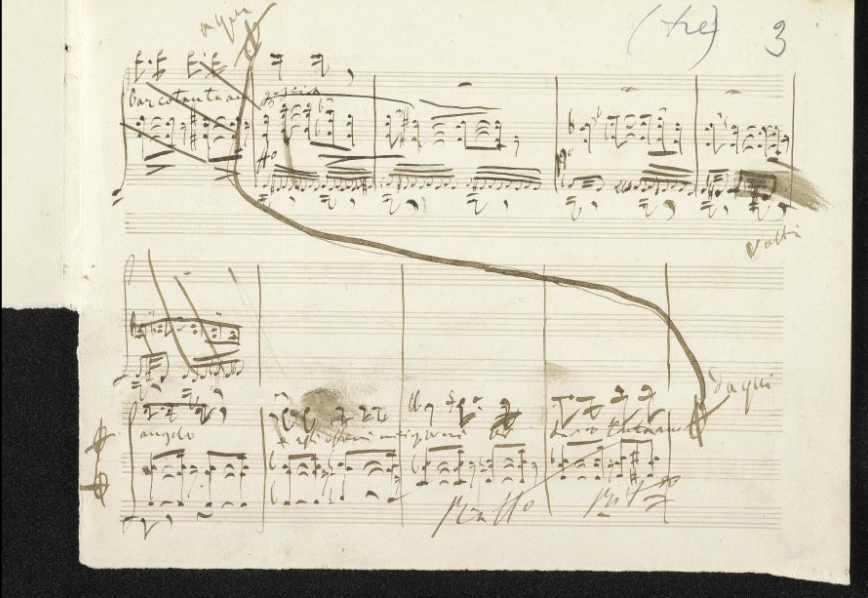

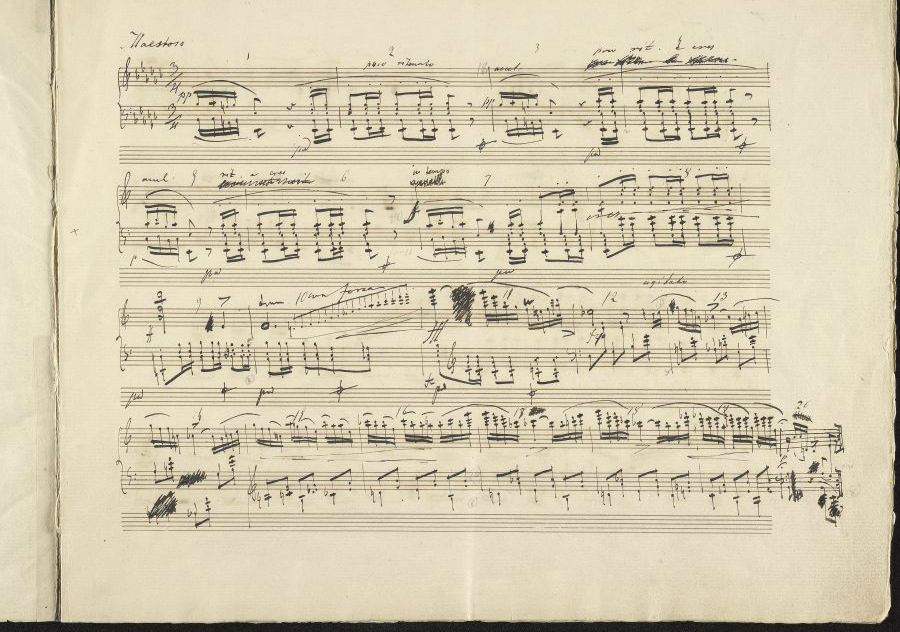

Or circumnavigate the scribbled out boo boos, while attempting Chopin’s Polonaises, Piano, Op. 26. Chopin’s John Hancock is the reward.

The hits just keep coming: Beethoven, Brahms, Debussy, Fauré, Haydn, Liszt, Mahler, Massenet, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Schumann…

Not surprisingly, female composers are grossly underrepresented, but there are a few gems, such as Mendelssohn’s sister Fanny Hensel’s autographed manuscript of the song Selmar und Selma, decorated with a pretty pencil and wash drawing by her husband

The Morgan has plans to add essays about the manuscripts by leading scholars. In the meantime, pick a piece and start practicing.

Related Content:

The World Concert Hall: Listen To The Best Live Classical Music Concerts for Free

85,000 Classical Music Scores (and Free MP3s) on the Web

All of Bach for Free! New Site Will Put Performances of 1080 Bach Compositions Online

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday