While there have of course been numerous attempts at movie magic that have resulted in something less than audience pleasing, only a few demonstrate such bold ineptitude as to become “so bad that they’re good.” Such a film requires a strong sense of vision coupled with a complete inability to realize that vision in a coherent way, and it must display real charm, as we see through the presentation to behold real human beings captured in the poignancy of their doomed filmic endeavor.

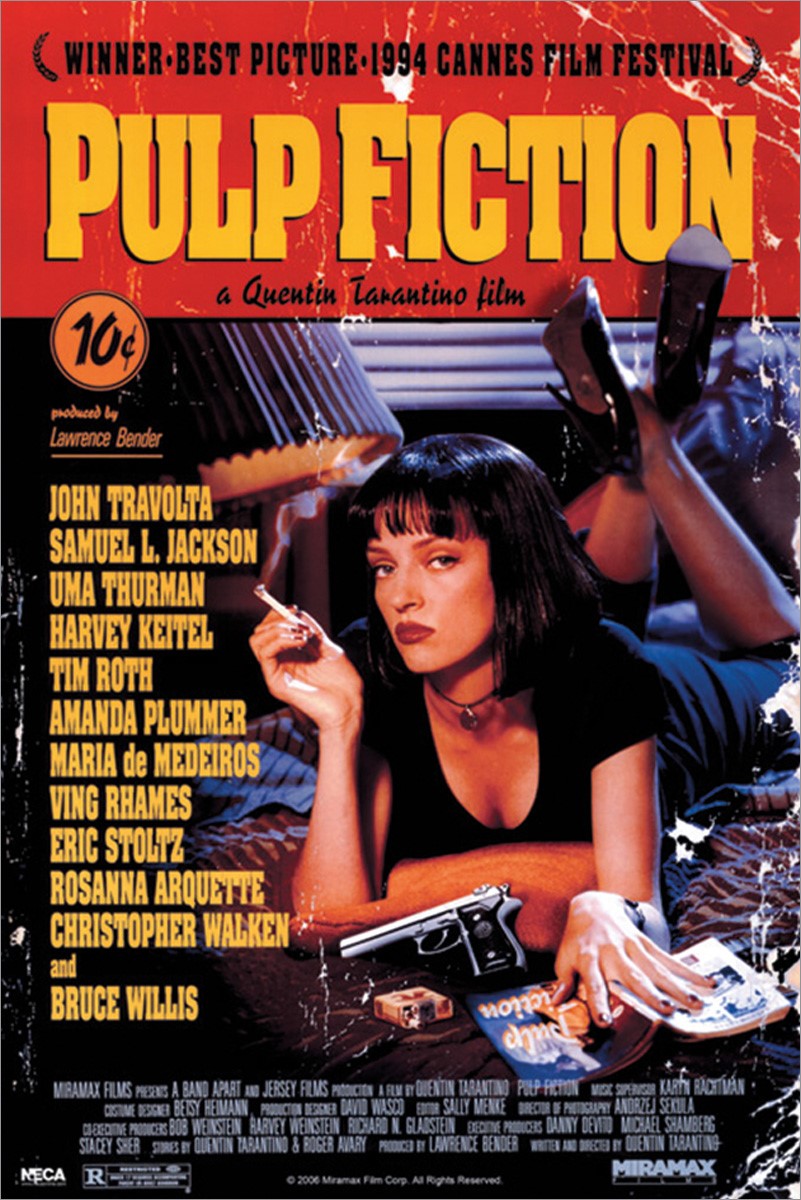

Some often cited candidates for this new kind of film canon include the classic Plan 9 from Outer Space, whose creation was dramatized in Tim Burton’s film Ed Wood; Tommy Wiseau’s The Room, chronicled by the book and film The Disaster Artist; Troll 2, a film that has no business or creative relation to the already dubious film Troll that was documented in Best Worst Movie; and the an up-and-comer Birdemic: Shock and Terror, self-financed by James Nguyen, whose popularity greatly increased through the treatment of his films by Rifftrax, one of the TV show Mystery Science Theater 3000’s Internet successors.

And then there’s Manos: The Hands of Fate, lauded as one of the most trippy finds of the original 1993 MST3K. It’s a film written, directed by, and starring (literal) fertilizer salesman Harold P. Warren about a family (on their “first vacation”) getting lost in Western Texas and ending up staying the night at a house with a religious cult. Jackey Neyman Jones played the six-year-old girl in the film who eventually (spoiler!) ends up tied to a stake as the cult leader’s seventh wife. Her father played the cult leader and created much of the art for the show, her mother sewed the costumes, and her voice was dubbed over by a fully grown woman who was not at all warned that she’d be having to imitate a child’s voice.

Jackey wrote a memoir about the experience, and here joins your Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica, Spyres, and Brian Hirt to talk about the ongoing interest in the film despite its initial, complete dismissal as well as the dynamics and perils of working with a supremely confident “auteur.”

The discussion also touches on other bad films like Catwoman, The Happening, and Battleship. Are these contemporary, big-budget flops worthy of such canonization? What about films made intentionally to be cheesy, whether by auteurs like Velocipastor or pumped out by a company like Syfy’s Sharknado series?

You can watch Jackey read her entire book online. See her art. Read her interviewed in Cracked, Entertainment Weekly, and the AV Club. Check out her IMDB page and her short-lived Hand of Horror podcast. Manos: The Hands of Fate is in the public domain, so watch it unriffed if you dare, or check out the classic MST3K episode or the more recent Rifftrax treatment. See also the warped stage version with puppets: Manos: The Hands of Felt.

To think more generally about this topic, we consulted some lists of bad (or “so-bad-they’re-good”) films by The Ringer, Thrillist, Screenrant, Yardbarker, and Wikipedia.

Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.