The technology used to produce, record, and process music has become ever more sophisticated and awe-inspiring, especially in the capability of software to emulate real instruments and acoustic environments. Digital emulation, or “modeling,” as it’s called, doesn’t simply mimic the sounds of guitar amplifiers, pianos, or synthesizers. At its best, it reproduces the feel of an aural experience, its textures and sonic dimensions, while also adding a seemingly infinite degree of flexibility.

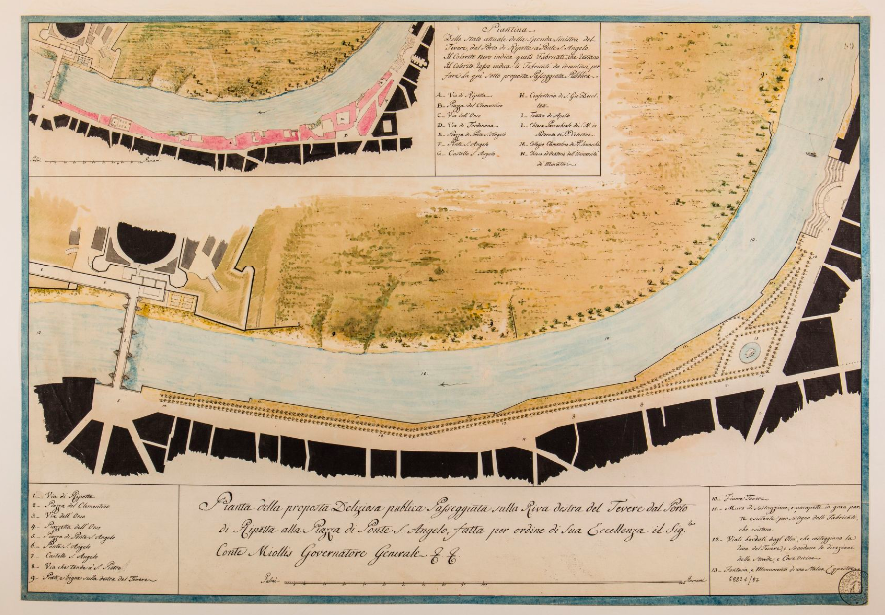

When it comes to a technology called “convolution reverb,” we can virtually feel the air pressure of sound in a physical space, such that “listening in may be viewed as much as a spatial experience as it is a temporal one.” So notes Stanford’s Icons of Sound, a collaboration between the University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) and the Department of Art & Art History. The researchers in this joint project have combined resources to create a performance of Byzantine chant from the 6th century CE, simulated to sound like it takes place inside a prime acoustic environment designed for this very music, the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Built by the emperor Justinian between 532 and 537, when the city was Constantinople, the massive church (later mosque and now state-run museum) “has an extraordinarily large nave spreading over 70 meters in length; it is surrounded by colonnaded aisles and galleries. Marble covers the floor and walls.” Its center is “crowned by a dome glittering in gold mosaics and rising 56 meters above the ground.” The effect of the building’s heavy, reflective surfaces and its architectural enormity “challenges our contemporary expectation of the intelligibility of language.”

We are accustomed to hear the spoken or sung word clearly in dry, non-reverberant spaces in order to decode the encoded message. By contrast, the wet acoustics of Hagia Sophia blur the intelligibility of the message, making words sound like emanation, emerging from the depth of the sea.

The Icons of Sound team has reconstructed the underwater acoustics of the Hagia Sophia using convolution reverb techniques and what are called “impulse responses”—recordings of the reverberations in particular spaces, which are then loaded into software to digitally simulate the same psychoacoustics, a process known as “auralization.” CCRMA describes an impulse response as an “imprint of the space,” which is then applied to sounds recorded in other environments. Typically, the process is used in studio music production, but Icons of Sound brought it to live performance at Stanford’s Bing Concert Hall last year, and made the group Cappella Romana sound like their voices had transported from the Holy Roman Empire.

“To recreate the unique sound,” writes Kat Eschner at Smithsonian, “performers sang while listening to the simulated acoustics of Hagia Sophia through earphones. Their singing was then put through the same acoustic simulator and played during the live performance through speakers in the concert hall.” As you can hear in these clips, the result is immersive and profound. One can only imagine what it must have been like live. To complete the effect, the production used “atmospheric reinforcement,” notes Stanford Live, “via projected images and lighting.” The audience was “immersed in an environment where the unique interplay of music, light, art, and sacred text has the potential to induce a quasi-mystical state of revelation and wonder.”

The only sounds the researchers were able to record in the actual space of the ancient church were four popping balloons. By layering the reverberations captured in these recordings, and compensating for the different decay times inside the Bing, they were able to approximate the acoustic properties of the building. You can hear several more audio samples recorded in different places at this site. In the video above, associate professor of medieval art Bissera Pentcheva explains how and why the Hagia Sophia shapes sound and light the way it does. While purists might prefer to see a performance in the actual space, one must admit, the ability to virtually deliver a version of it to potentially any concert hall in the world is pretty cool.

Related Content:

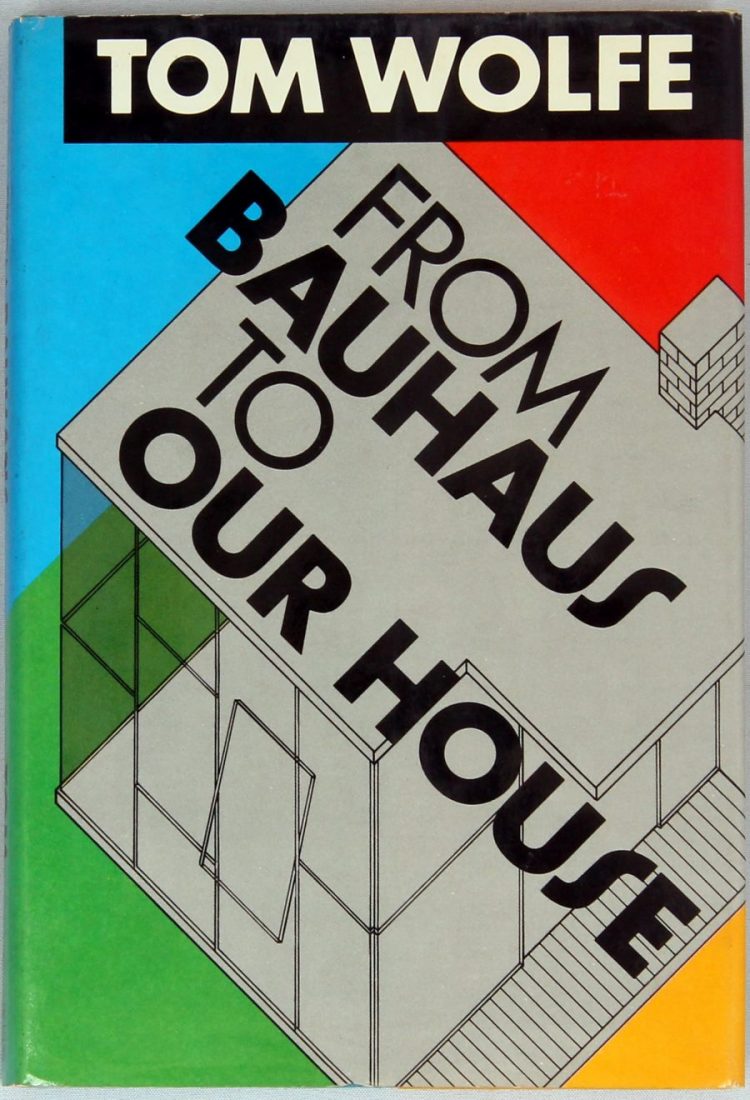

David Byrne: How Architecture Helped Music Evolve

What Did Ancient Greek Music Sound Like?: Listen to a Reconstruction That’s ‘100% Accurate’

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.