FYI: If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

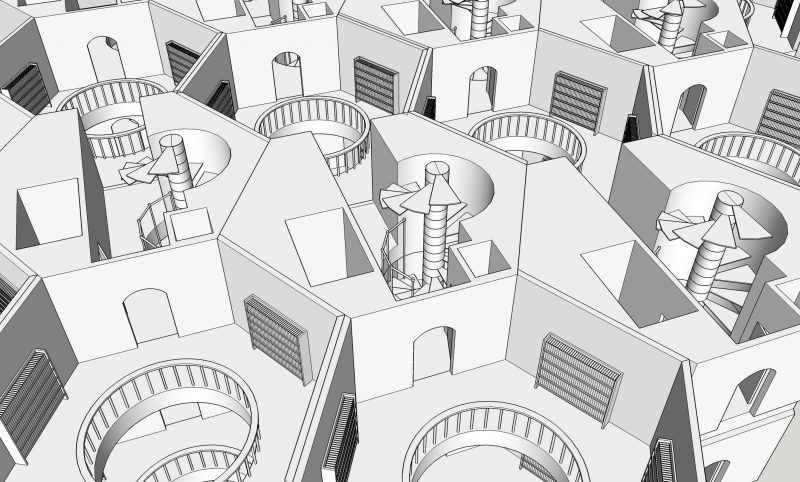

“Most of our cities are built with just faceless glass, only for economies and not for humanities.” We’ve all heard many variations on that complaint from many different people, but seldom with the authority carried by the man making it this time: Frank Gehry, author of some of the most talked-about buildings of the past thirty years. You may love or hate his work, the body of which includes such striking, formally and materially unconventional buildings as Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Concert Hall, and Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture, but you can’t remain indifferent to it, and that alone tells us how deeply Gehry understands the power of his craft.

And so when Gehry talks architecture, we should listen. Masterclass, the online education startup that has produced courses in various disciplines with such high-profile practitioner-teachers as David Mamet, Herbie Hancock, Jane Goodall, Steve Martin, and Werner Herzog, has readied a rich opportunity to do so in the fall: “Frank Gehry Teaches Design and Architecture,” whose trailer you can view above. The $90 course promises a look into the creative process, as well as into the “never-before-seen model archive,” of this biggest of all “starchitects” whose “vision for what architecture could accomplish” has reshaped not just our skylines but “the imaginations of artists and designers around the world.”

As with any educational experience, the more thoroughly you prepare in advance, the more you’ll get out of it, and so, to that end, we suggest watching Sydney Pollack’s documentary Sketches of Frank Gehry, recently made available online by the Louis Vuitton Foundation. “Pollack is not usually a documentarian, and Gehry has never been documented; they were friends, and Gehry suggested Pollack might want to ‘do something,’ ” wrote Roger Ebert in his review. “Because Pollack has his own clout and is not merely a supplicant at Gehry’s altar, he asks professional questions as his equal, sympathizes about big projects that seem to go wrong and offers insights.”

Pollack also “has access to the architect’s famous clients, like Michael Eisner,” commissioner of the Disney Concert hall, “and Dennis Hopper, who lives in a Gehry home in Santa Monica” — just as Gehry himself does, in the house whose radical, quasi-industrial modification did much to make his name. Though he also brings in a few of the architect’s many critics to provide balance, “Pollack’s opinion is clear: Gehry is a genius.” You may think so too, which would be a good a reason as any to take his Masterclass. Even if you think the opposite, the physical and cultural impact of Gehry’s work, as well as his enduring relevance and industriousness — he continues to design today, in his late eighties, especially for his long-ago adopted hometown of Los Angeles — has something to teach us all.

Related Content:

Gehry’s Vision for Architecture

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.