The purpose of the monumental druidical structure known as Stonehenge has been lost to us, but many theories abound, “from the rational to the irrational to the magical.” On the magical end of the scale, we have the giant stones associated with King Arthur and the wizard Merlin. On the more rational side, speculation that the structure functioned as a calendar for religious ceremonies or agricultural seasons.

While the search for answers may be irresistible, we may never know exactly what the builders of Stonehenge intended. But we learn much by studying how others have approached the ancient monument in the past. Existent studies of Stonehenge with illustrations date back to the 14th century. These Medieval representations tried to situate the stones in a “Christian view of world history,” as Art History professor Sam Smiles writes at the British Library.

A century later, drawings of the stones show more of an interest in its architectural features. One manuscript includes “a tiny illustration of four trilithons (two vertical stones supporting a lintel).” Remarkably, writes Smiles, “the artist has understood how the lintels were fixed to the uprights by a mortise and tenon joint.” The drawing may represent “the earliest surviving representation of Stonehenge based on direct observation.”

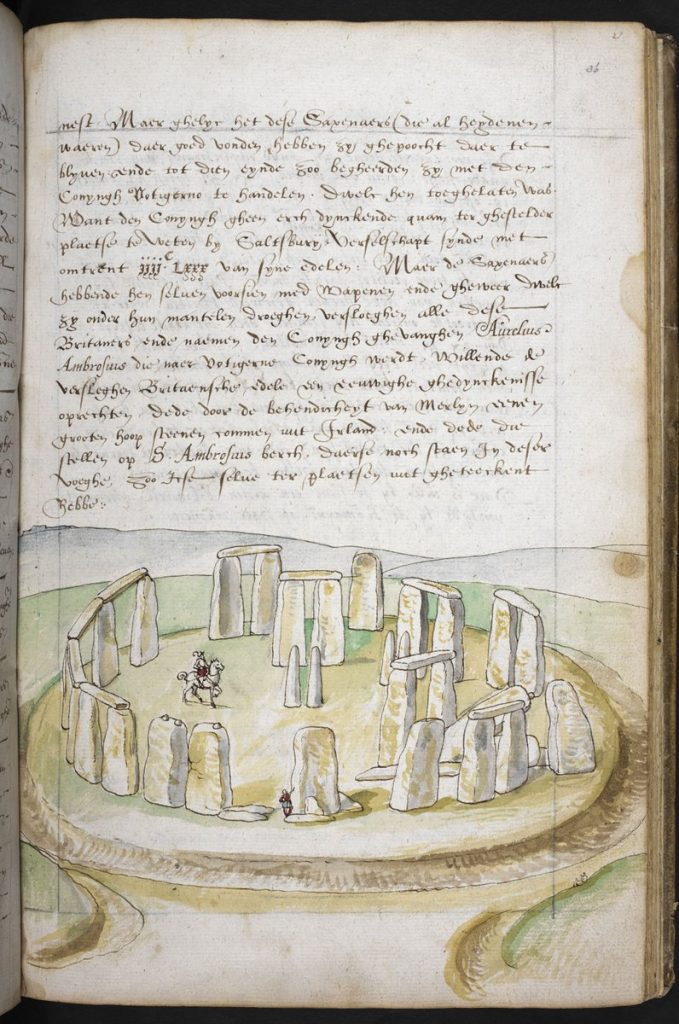

The practice of drawing Stonehenge from life continued, and in the watercolor above by Flemish painter Lucas de Heere, dating from circa 1573, we see “a more topographical approach.” Related to other similar images created around the same time, the painting shows us an early example of what came to be called “chorography,” which archaeologist Michael Shanks describes as referring to “antiquarian works that dealt in topography, place, community, history, memory.”

Rather than considering it only as a mystical or sacred site or an architectural marvel, de Heere’s depiction of Stonehenge folds both of these interests into a larger concern with English landscape and history, of the kind exemplified by William Camden’s 1586 Britannia, a chorographical survey of Britain and Ireland. Works like de Heere’s and Camden’s are part of the “Re-Discovery of England,” as historian R.C. Richardson argues, that took place under the reign of Elizabeth I, and which produced a new national history, “designed to extend the boundaries of knowledge and understanding.”

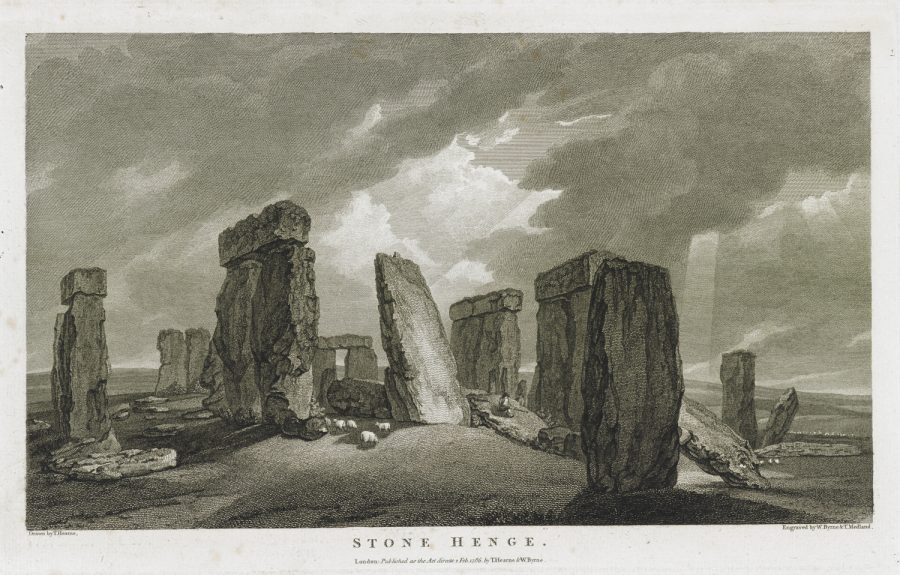

As chorography developed as a discipline, Stonehenge and other ancient monuments continued to exert a fascination for their historical, topographical, and archeological features. By the “last quarter of the 18th century,” Smiles tells us, “prehistoric monuments began to be regularly included in topographical surveys,” such as Thomas Hearne’s 1779 Antiquities of Great Britain, which included the engraving just above as its final plate. Learn more about the development of topography and its interest in ancient British monuments, and see many more of these historic images, at the British Library’s site.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Manuscript of Beowulf Digitized and Now Online

A Free Yale Course on Medieval History: 700 Years in 22 Lectures

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness