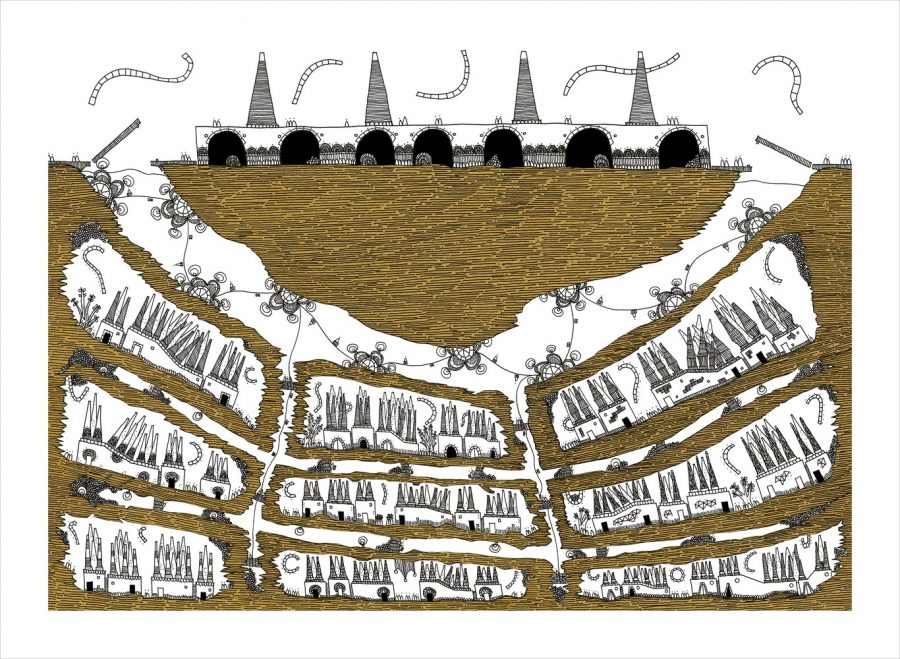

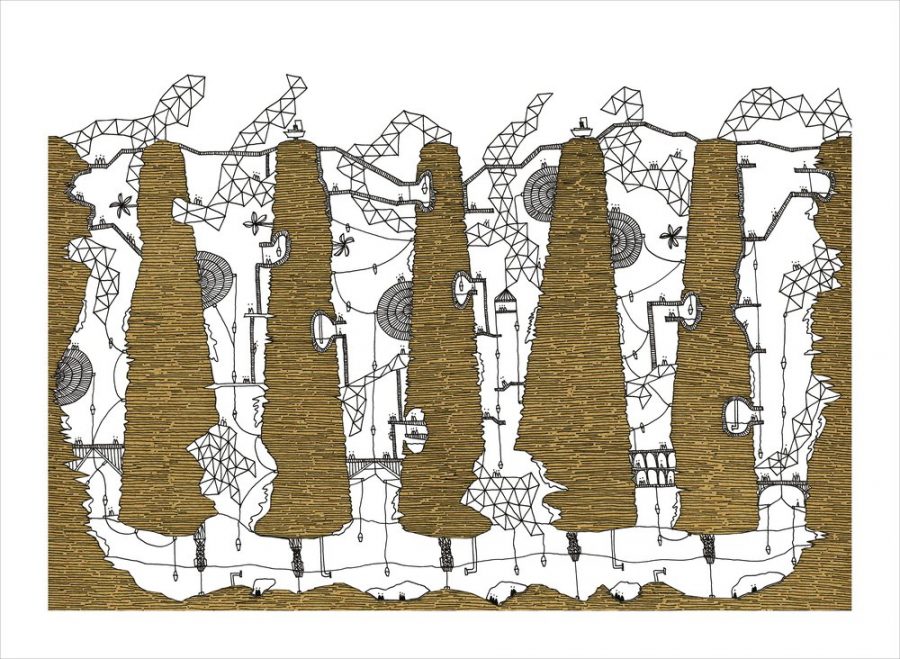

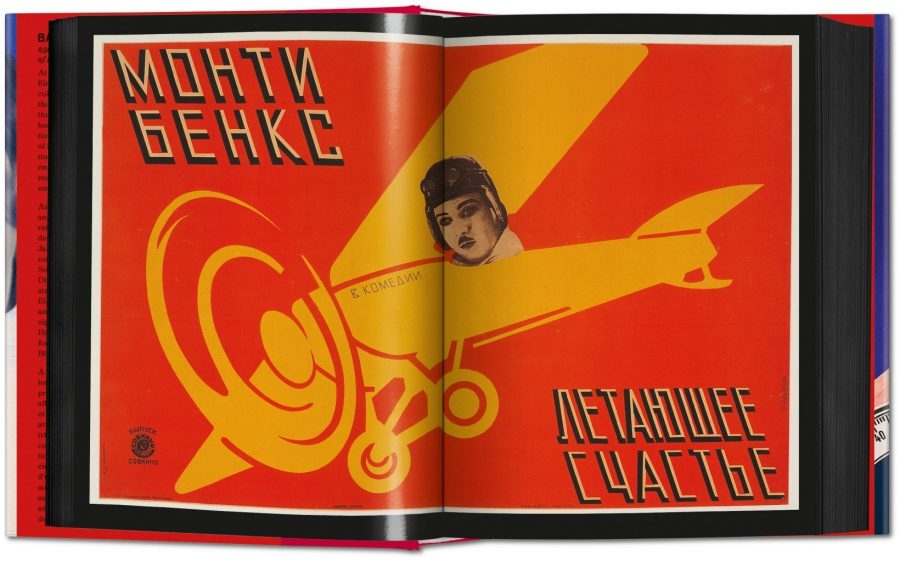

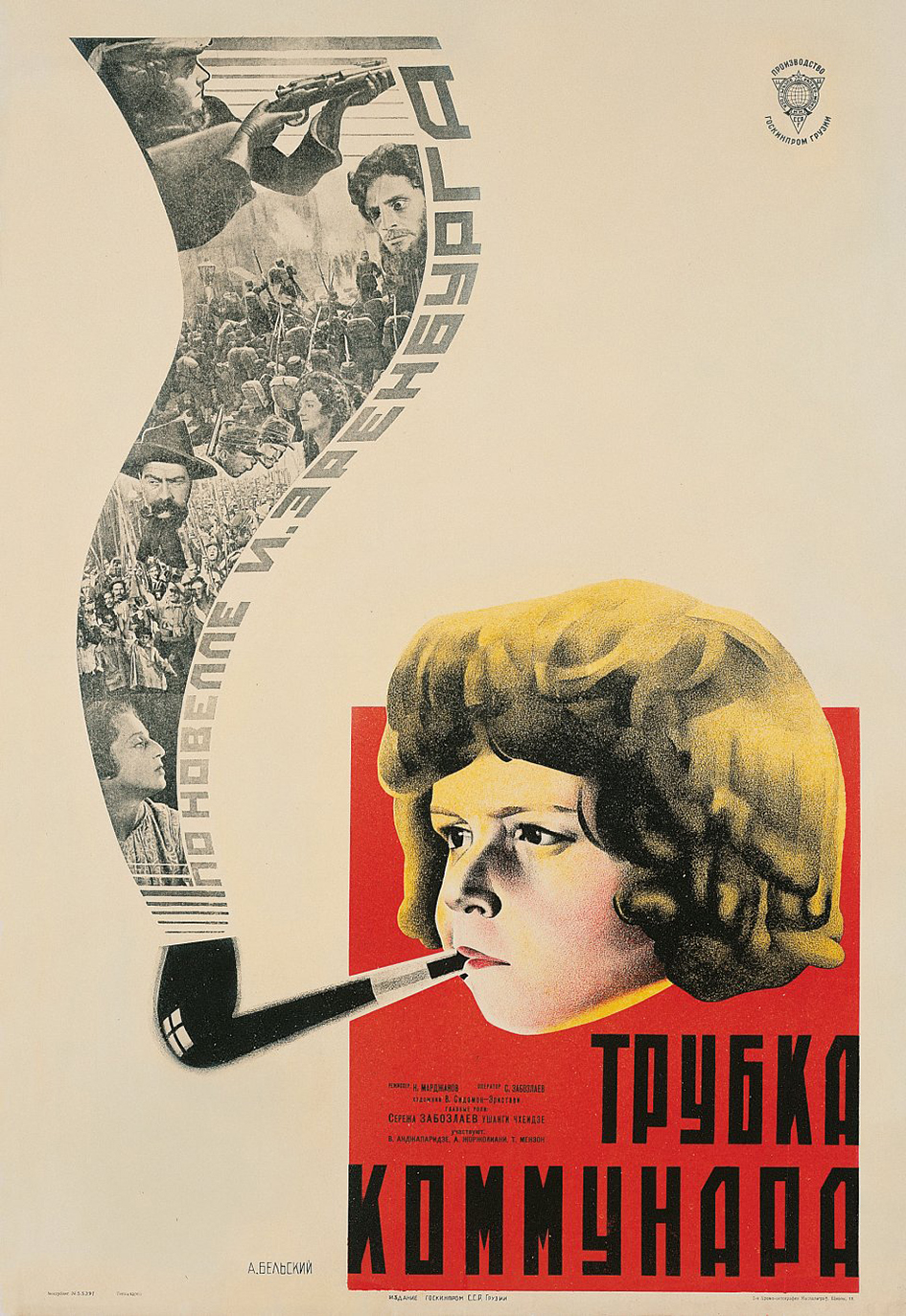

To commemorate the centennial of Russia’s October Revolution (it seems like only yesterday, comrade!) Taschen has yet again delivered an impressive tome of a book, entitled Film Posters of the Russian Avant-Garde. Collector Susan Pack has put together this selection of 250 posters by 27 artists for films both well known and lost to history.

The book first came out in 1995, but this new edition is smaller and multilingual, like many of their new releases.

The style still impresses and influences today, with its combination of photo-realist faces and the jagged energy of constructivism.

Many of the artists never saw the films they were advertising, but plainly not a bad thing here. Artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko (who was also a designer and photographer) and the Stenberg Brothers (sculptors and set designers) mixed photos with lithographs, incorporated the film’s credits into the actual art, and worried not about selling the story beyond a basic excitement level. This was art designed to get people in the door, regardless of the film. And, if you think about it, it’s art that could not exist in this current era. Who would commission a film poster blindly? Nobody, my friend.

Still, it was in no way ideal for the artists. They often had less than a day to finish something, and the printing presses were pre-revolution vintage and in various stages of repair. And very few, we can assume, thought their posters would be saved and collected. Pack’s collection often contains the only surviving copies of a certain work.

Stalin stopped all this once he took power and insisted that only socialist realism be depicted in art. This style has its own collectors, for sure, but there’s always a tinge of kitsch to it all, because it reveals the lie that was the Stalin era. Whereas the dynamism of these early posters still maintain their aesthetic hold, springing from a time where hope, excitement, and revolution were pulsing through the country and its populace.

via Vice/Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Striking French, Russian & Polish Posters for the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.