Oh sure, they look festive, but seriously, think twice before arming a blindfolded child (or a beer guzzling adult guest) with a sturdy stick and encouraging him to swing wildly.

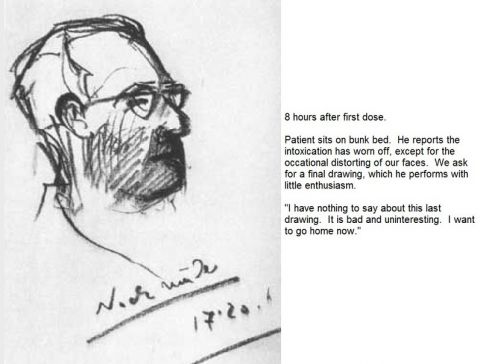

There’s no need to worry, however, about anyone taking a bat to the intricate Hieronymus Bosch-inspired piñatas of Roberto Benavidez, a self-described half-breed, South Texan, queer figurative sculptor.

Even if you filled them with candy, the exteriors would be far more valuable than any treasures contained within.

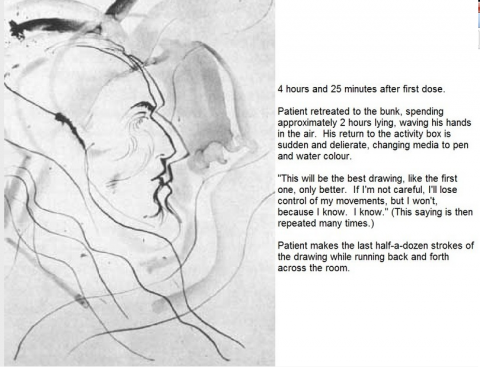

Bosch, of course, excelled at scenarios far more nightmarish than anything one might encounter in a backyard party. Benavidez seems less drawn to that aspect than the beauty of the fantastical creatures populating The Garden of Earthly Delights.

In fact, the majority of his papier-mâché homages are drawn from the paradisiacal left panel of the famous triptych.

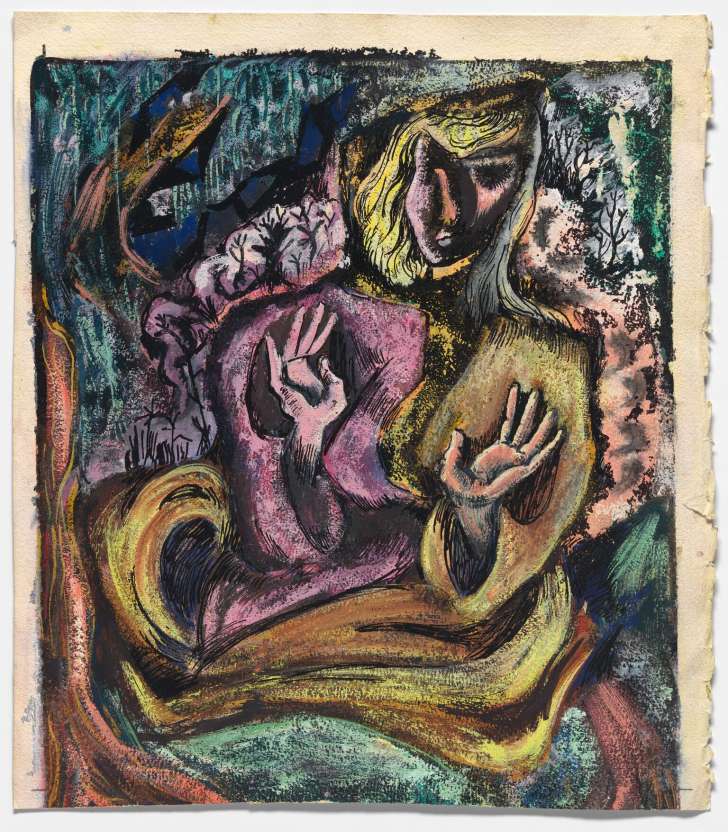

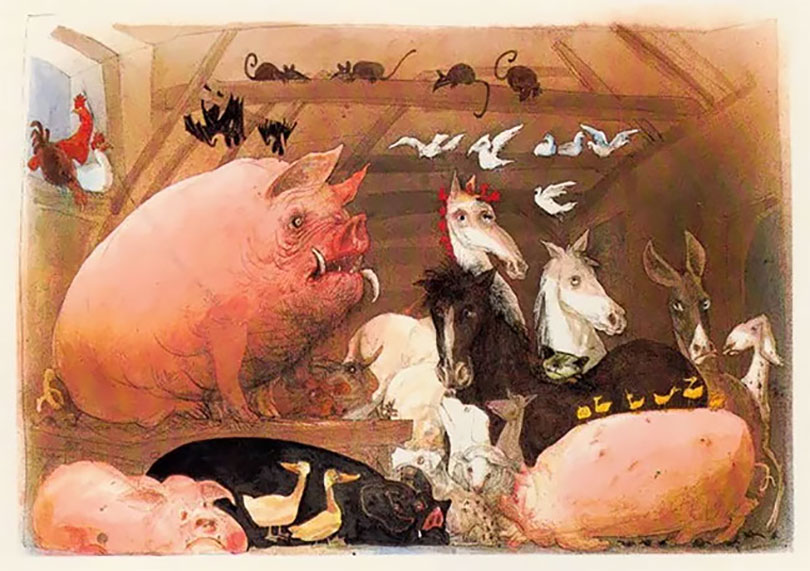

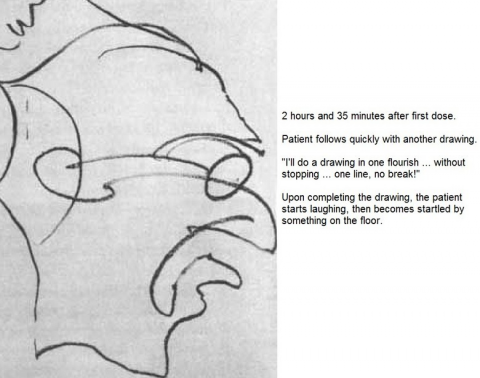

Not so the first in the series, 2013’s superbly titled Piñata of Earthly Delights #1, above

In the original, a misshapen waterbird uses its long beak to spear a cherry with which it tempts a passel of weak-willed mortals, crowded together inside a spiky pink blossom.

In Benavidez’s version the lack of naked humans allows us to focus on the creature, whose beak now pierces a simple star-shaped piñata of its own.

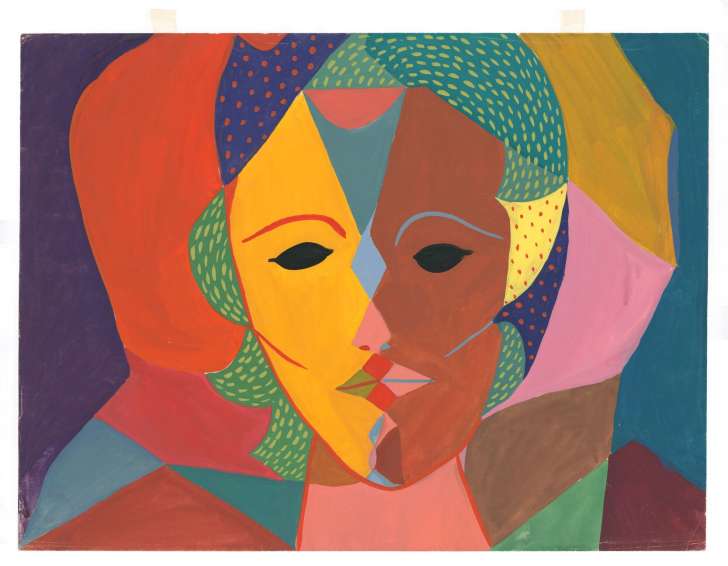

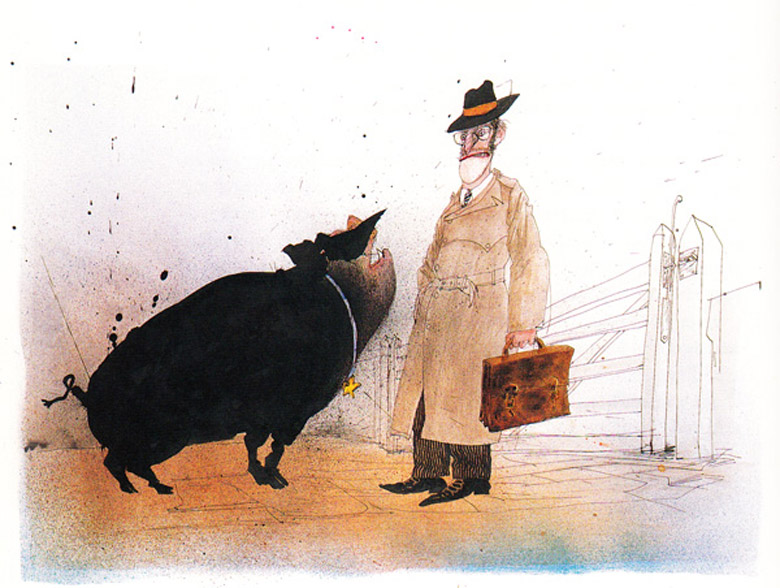

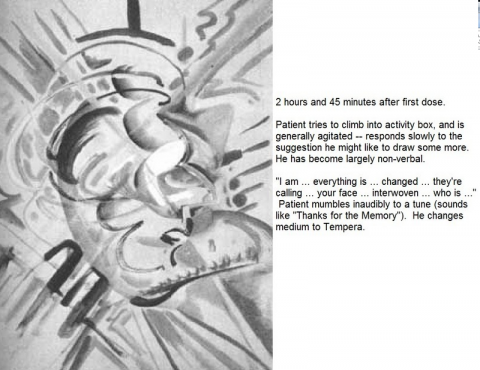

Those with a fascination for the antics of Bosch’s party people are invited to play a variation of Where’s Waldo, scouring the painting for the inspiration behind Candy Ass Bottom, above.

(Hint: if you’re gravitating toward those posteriors serving as vessels for flutes, flocks of blackbirds, or red hot pokers, you’re getting colder…)

While little is known about Bosch’s artistic training, Benavidez majored in acting, before returning to his childhood fascination for sculpting, taking classes in drawing, painting, and bronze casting at Pasadena City College. Thrift and portability led him to begin exploring paper as his primary medium.

As he remarked on the blog of the crepe paper manufacturer Cartotecnica Rossi:

I was intrigued by the idea of taking the piñata form, something seen as cheap and disposable, and moving it into the arena of fine art. I feel that my sculptural forms and fringing techniques set my work apart from what most people think of as a typical piñata and the themes are more complex than is typical.

Definitely.

View more of Roberto Benavidez’ fine art piñatas, including those inspired by Hieronymus Bosch on his website or Instagram feed.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.