If your Facebook news feed looks anything like mine, you wake up each morning to a stream of not just food snapshots and selfies but pictures of books, whether stacked up, dumped into a pile, or arranged neatly on shelves. Why do we post digital photos of our printed matter? Almost certainly for the same reason we do anything on social media: to send a message about ourselves. We want to tell our friends who we are, or who we think we are, but not in so many words, or rather not in so few; a few of the books we’ve read (or intend to read), carefully selected and arranged, does the job. But what if, instead of assembling a self-portrait through books, someone else entered your personal library and did it for you?

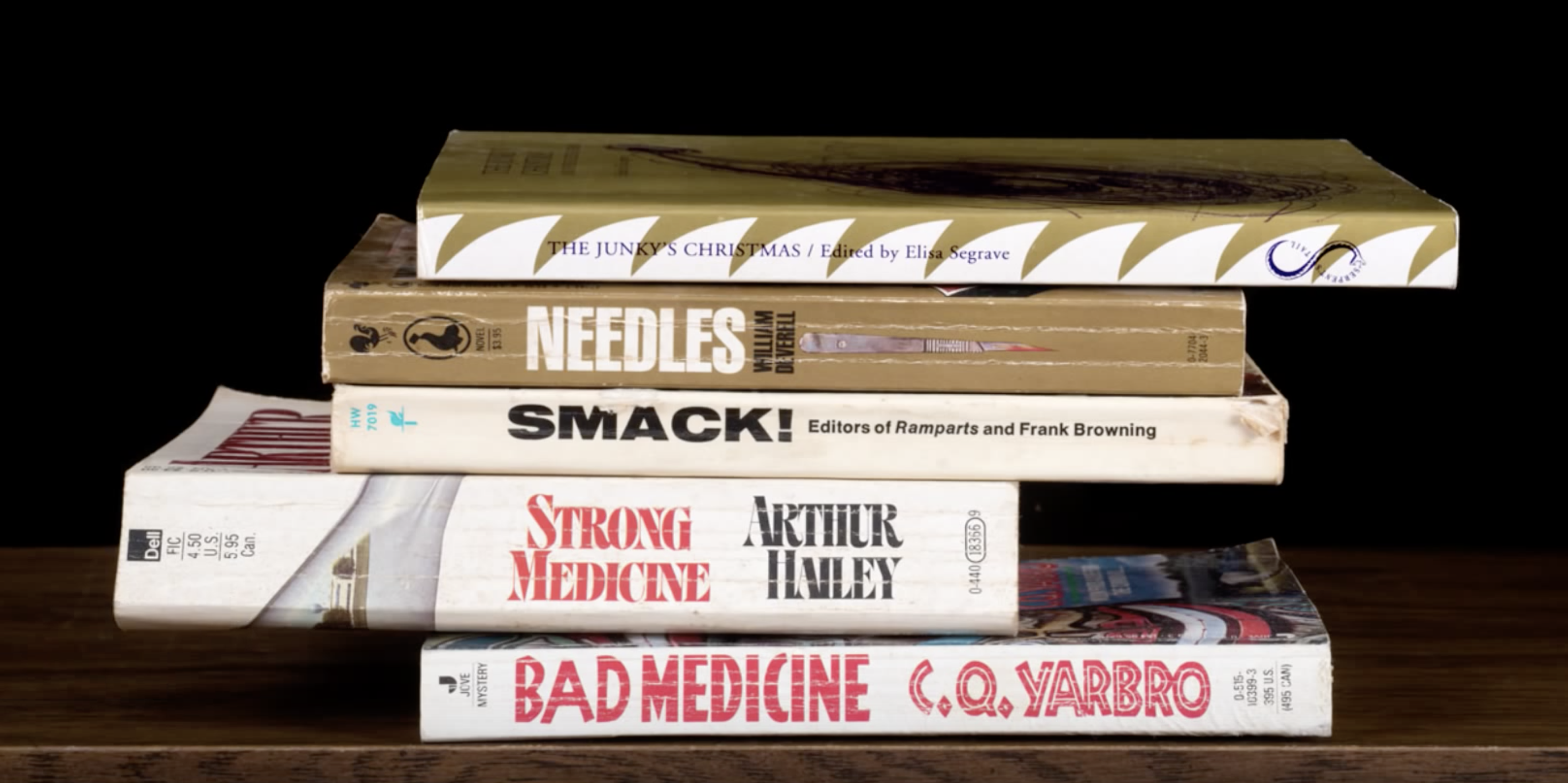

Artist Nina Katchadourian (she of, among many other endeavors, the airplane-bathroom 17th-century Flemish portraiture) recently took on that task in the Lawrence, Kansas home of famously hard-living and furiously creative beat writer William S. Burroughs. She did it as part of her long-running Sorted Books project, in which, in her words, “I sort through a collection of books, pull particular titles, and eventually group the books into clusters so that the titles can be read in sequence.

The final results are shown either as photographs of the book clusters or as the actual stacks themselves, often shown on the shelves of the library they came from. Taken as a whole, the clusters are a cross-section of that library’s holdings that reflect that particular library’s focus, idiosyncrasies, and inconsistencies.”

Kansas Cut-Up, the Burroughs chapter of Sorted Books, features such arrangements as How Did Sex Begin? / Uninvited Guests / Human Error, Memoirs of a Bastard Angel / A Night of Serious Drinking / A Little Original Sin, and American Diplomacy / Physical Interrogation Techniques / In the Secret State. Thom Robinson of the European Beat Studies Network describes Burroughs’ book collection as “a selection of largely European works whose contents include paranoia, theories of language, pseudoscience, mordant humour and drugs: in retrospect, it’s easy to imagine the owner of such an idiosyncratic library producing the melange of Naked Lunch. Perhaps for this reason, it seems hard to resist reordering the books which Burroughs owned in 1944 in order to emphasise the most recognisable elements of the later Burroughs persona.”

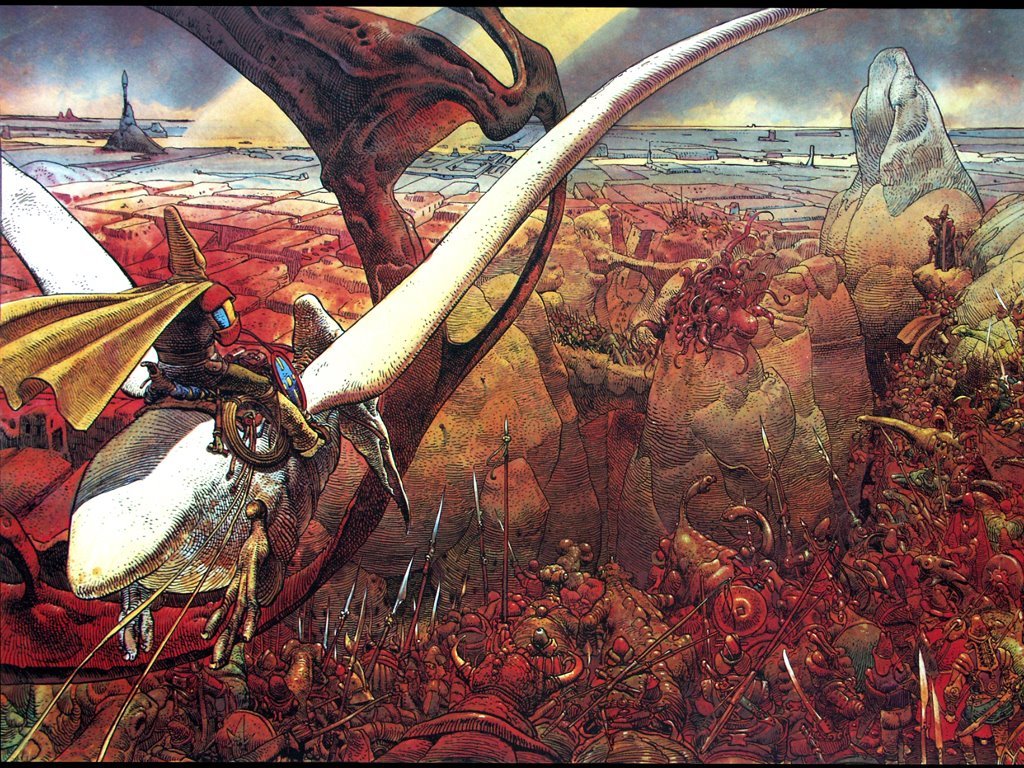

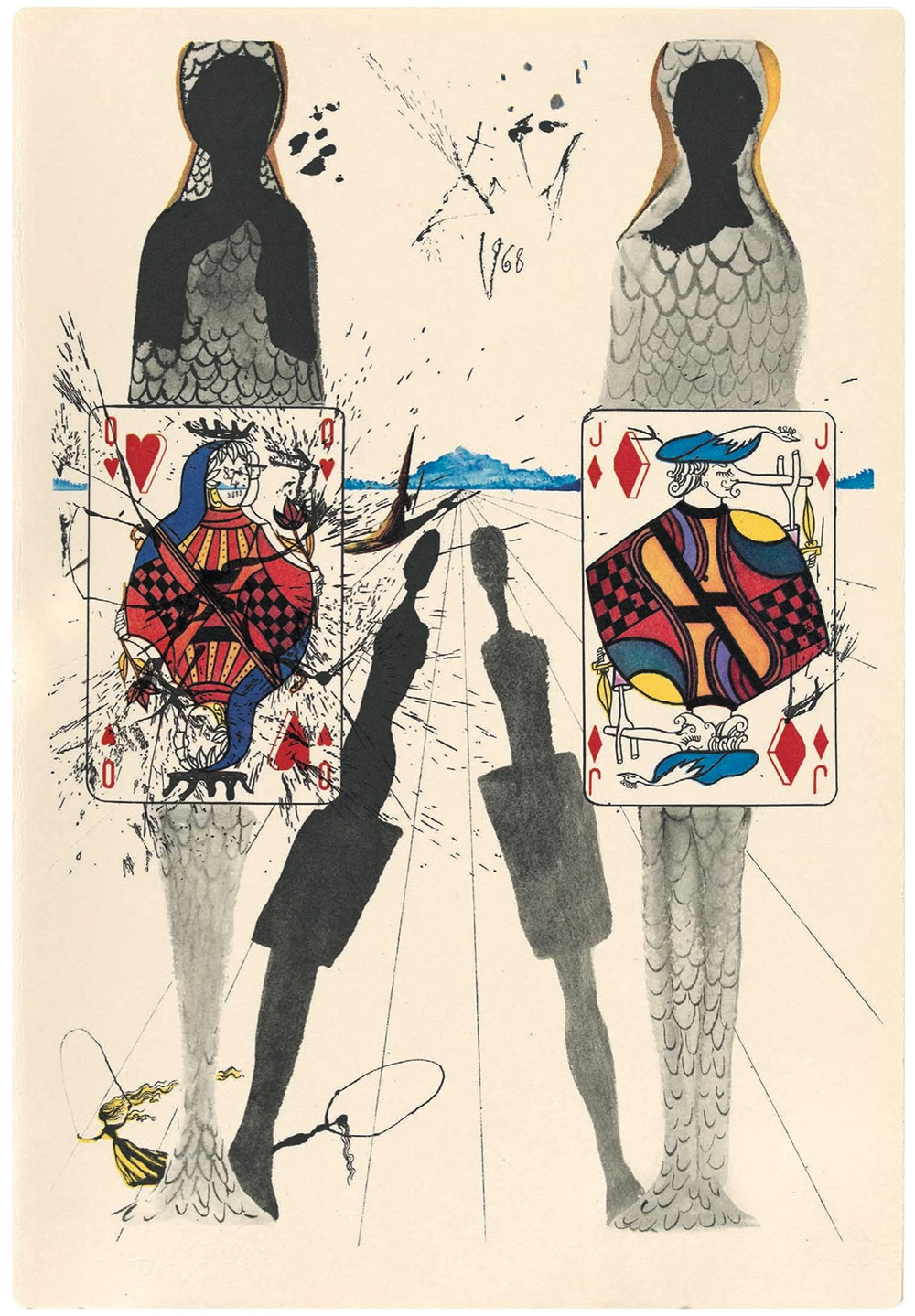

Sometimes Katchadourian seems to do just that and sometimes she doesn’t, but her method of book-sorting, which she explains in the episode of John and Sarah Green’s series The Art Assignment at the top of the post, bears more than a little resemblance to Burroughs’ own “cut-up” method of literary composition. “Take a page,” as Burroughs himself explained it. “Now cut down the middle and cross the middle. You have four sections: 1 2 3 4 … one two three four. Now rearrange the sections placing section four with section one and section two with section three. And you have a new page. Sometimes it says much the same thing. Sometimes something quite different.” And just as a rearranged book can speak in a new and strange voice, so can a rearranged library.

via Austin Kleon’s newsletter (which you should subscribe to here)

Related Content:

How to Jumpstart Your Creative Process with William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique

115 Books on Lena Dunham & Miranda July’s Bookshelves at Home (Plus a Bonus Short Play)

The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe’s Library: How Many Have You Read?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.