Quick, what do you know about Leonardo da Vinci? He painted the Mona Lisa! He wrote his notes backwards! He designed supercool bridges and flying machines! He was a genius about, um… a lot of other… things… and, um, stuff…

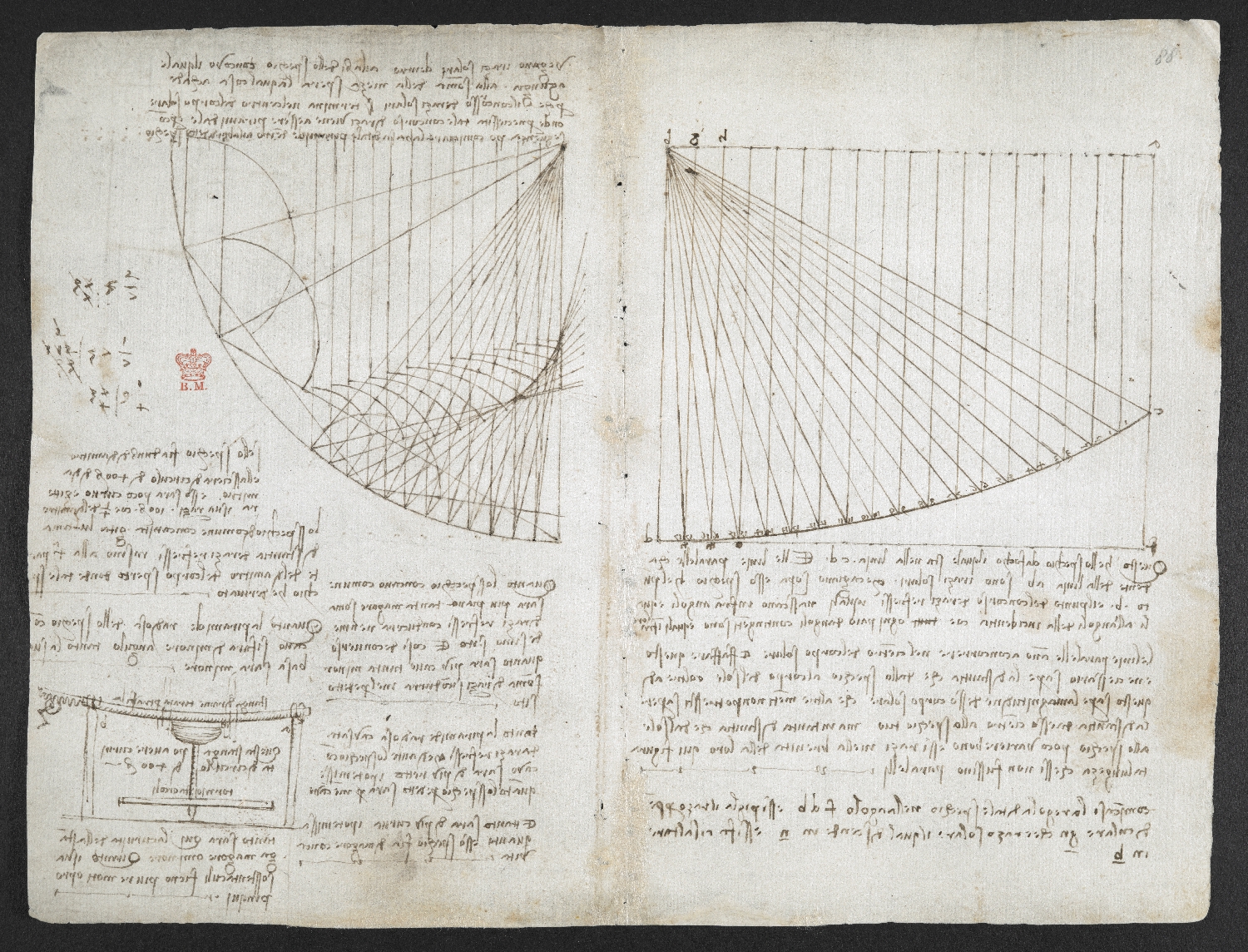

Okay, I’m sure you know a bit more than that, but unless you’re a Renaissance scholar, you’re certain to find yourself amazed and surprised at how much you didn’t know about the quintessential Renaissance man when you encounter a compilation of his notebooks—Codex Arundel—which has been digitized by the British Library and made available to the public.

The notebook, writes Jonathan Jones at The Guardian, represents “the living record of a universal mind.” And yet, though a “technophile” himself, “when it came to publication, Leonardo was a luddite…. He made no effort to get his notes published.”

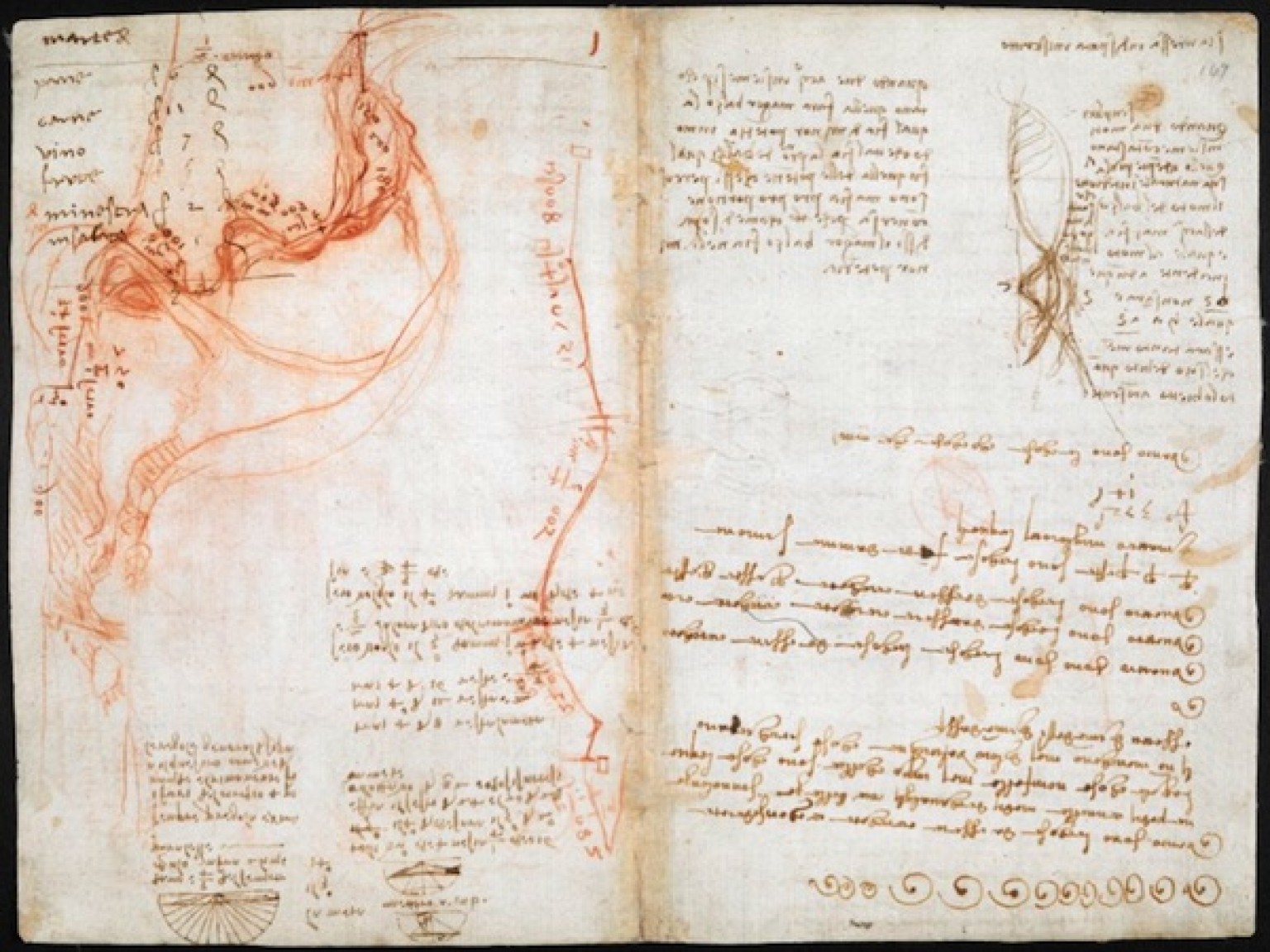

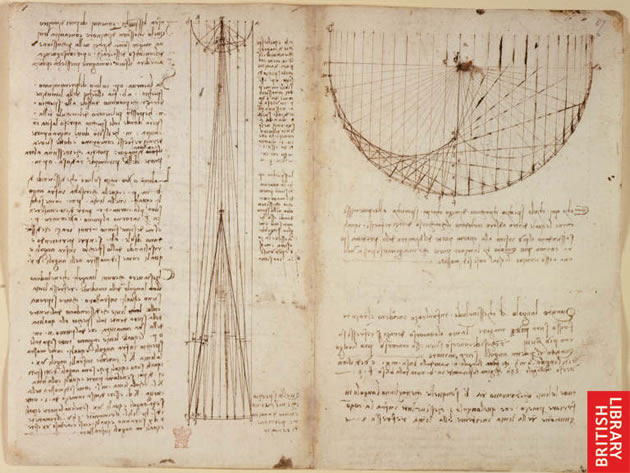

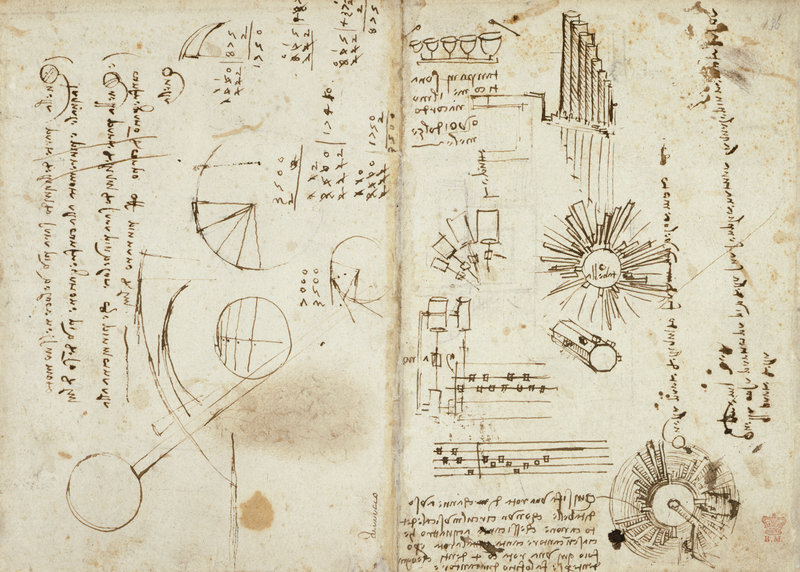

For hundreds of years, the huge, secretive collection of manuscripts remained mostly unseen by all but the most rarified of collectors. After Leonardo’s death in France, writes the British Library, his student Francesco Melzi “brought many of his manuscripts and drawings back to Italy. Melzi’s heirs, who had no idea of the importance of the manuscripts, gradually disposed of them.” Nonetheless, over 5,000 pages of notes “still exist in Leonardo’s ‘mirror writing’, from right to left.” In the notebooks, da Vinci drew “visions of the aeroplane, the helicopter, the parachute, the submarine and the car. It was more than 300 years before many of his ideas were improved upon.”

The digitized notebooks debuted in 2007 as a joint project of the British Library and Microsoft called “Turning the Pages 2.0,” an interactive feature that allows viewers to “turn” the pages of the notebooks with animations. Onscreen glosses explain the content of the cryptic notes surrounding the many technical drawings, diagrams, and schematics (see a selection of the notebooks in this animated format here). For an overwhelming amount of Leonardo, you can look through 570 digitized pages of Codex Arundel here. For a slightly more digestible, and readable, amount of Leonardo, see the British Library’s brief series on his life and work, including explanations of his diving apparatus, parachute, and glider.

And for much more on the man—including evidence of his sartorial “preference for pink tights” and his shopping lists—see Jonathan Jones’ Guardian piece, which links to other notebook collections and resources. The artist and self-taught polymath made an impressive effort to keep his ideas from prying eyes. Now, thanks to digitized collections like those at the British Library, “anyone can study the mind of Leonardo.”

Related Content:

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness