Would you believe that David Bowie, era-transcending pop star, actor, and avid reader, found not just the time to build a formidable art collection (auctioned off for $41 million last year at Sotheby’s), but to do quite a few paintings of his own? Even Bowie fans who know only his music will have seen one of those paintings, a self-portrait which made the cover of his 1995 album Outside. That same year he had his first show as a painter, “New Afro/Pagan and Work: 1975–1995,” at The Gallery, Cork Street.

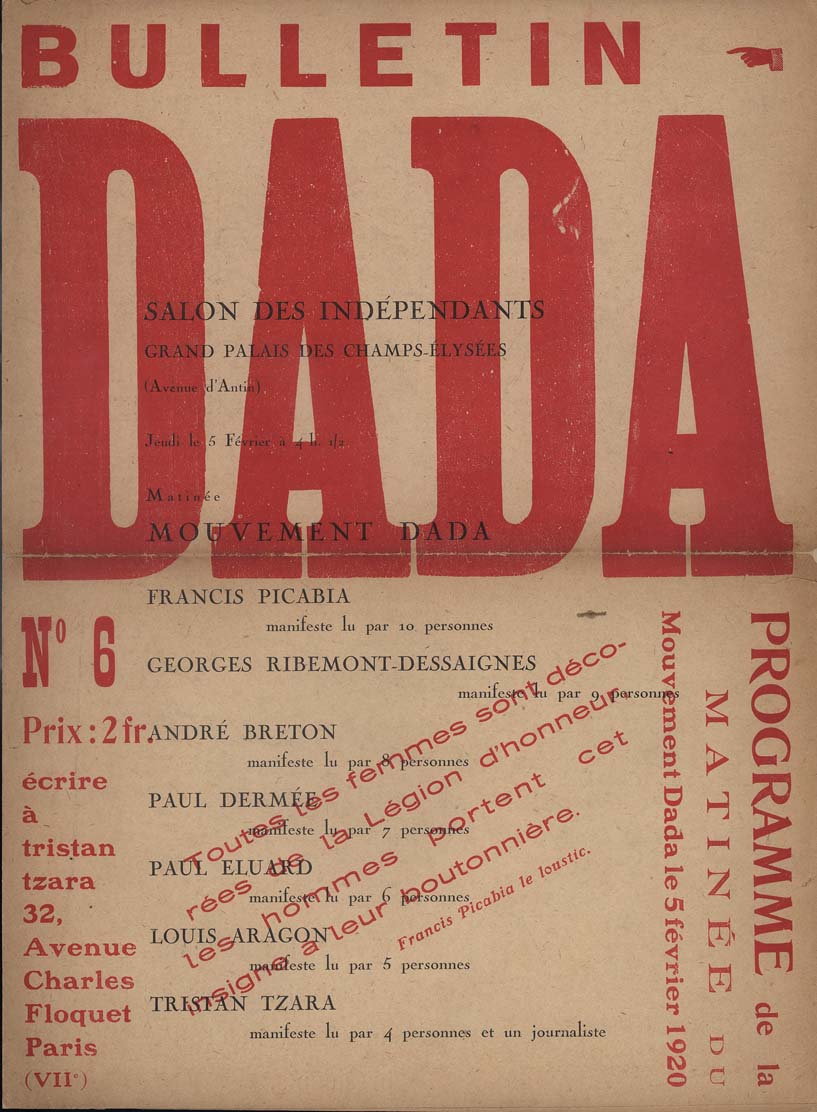

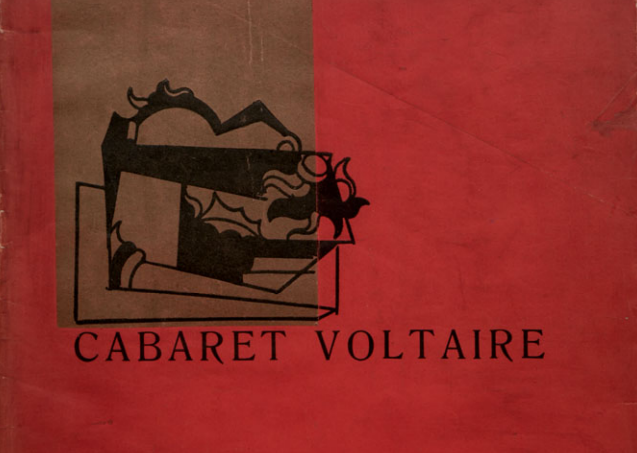

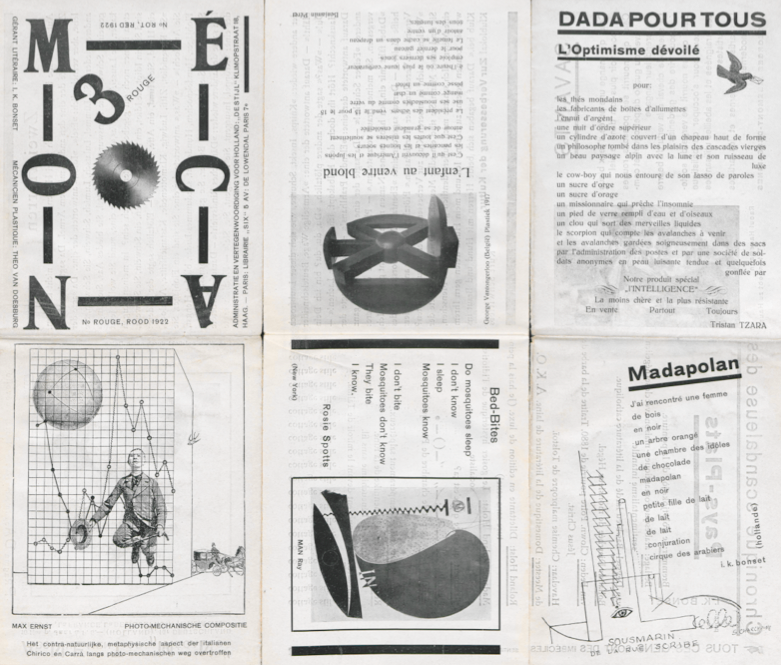

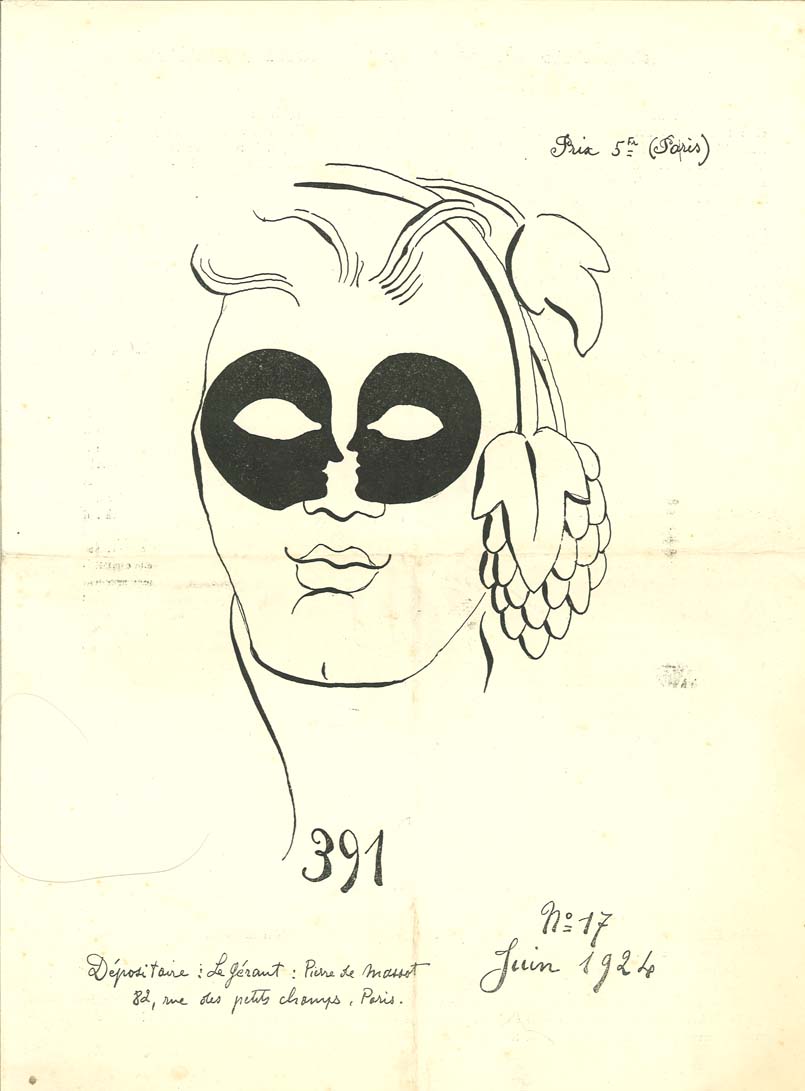

“David Bowie paintings show a knowledgeable approach to art, influenced by Frank Auerbach, David Bomberg, Francis Bacon, Francis Picabia…” says Very Private Gallery in a post on 25 of those works of art, adding that his style “also shows a touch of post-modernism, more precisely neo-expressionism movement.”

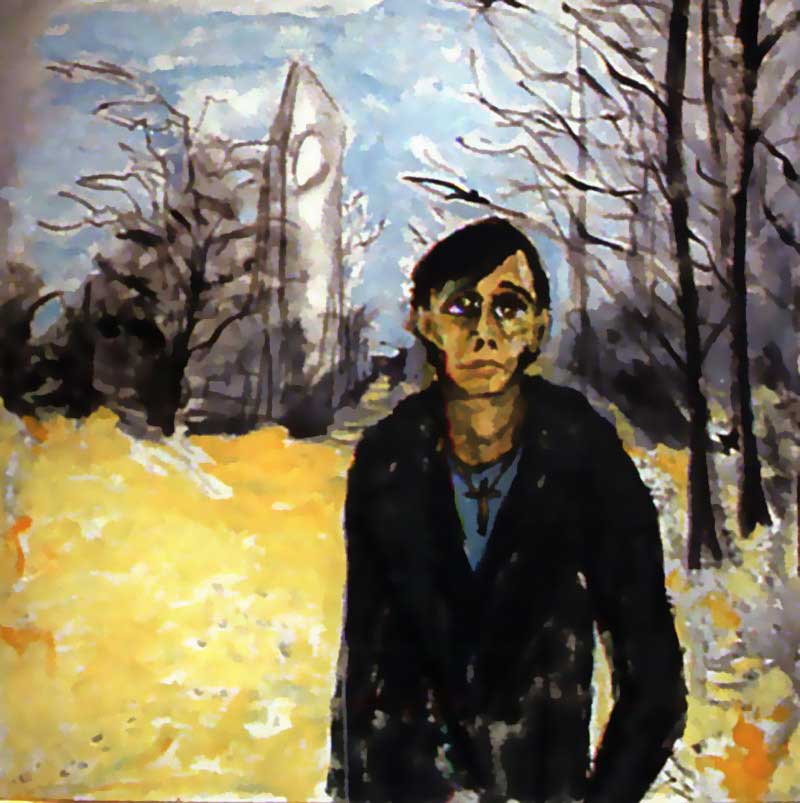

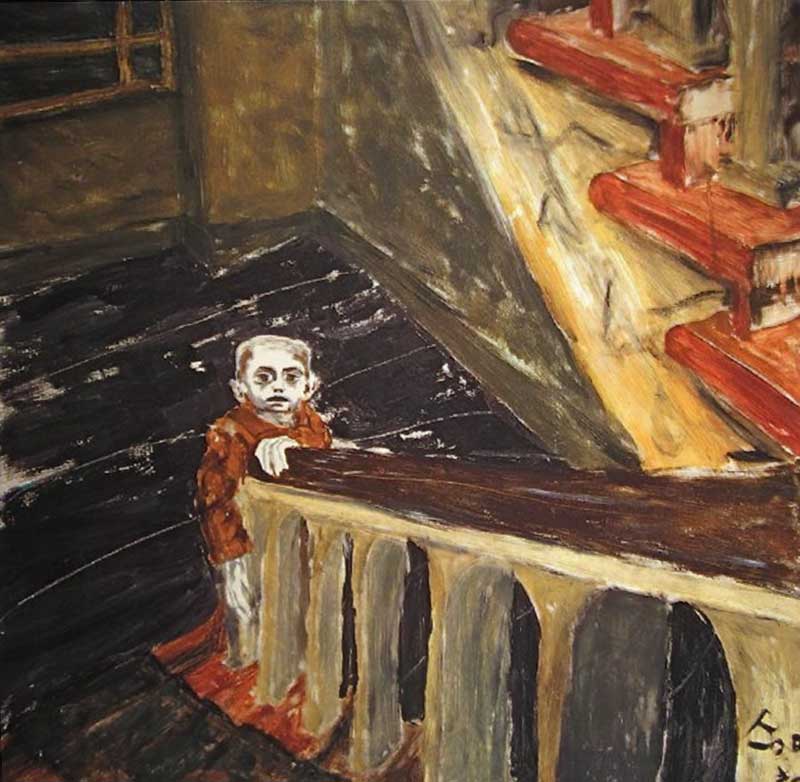

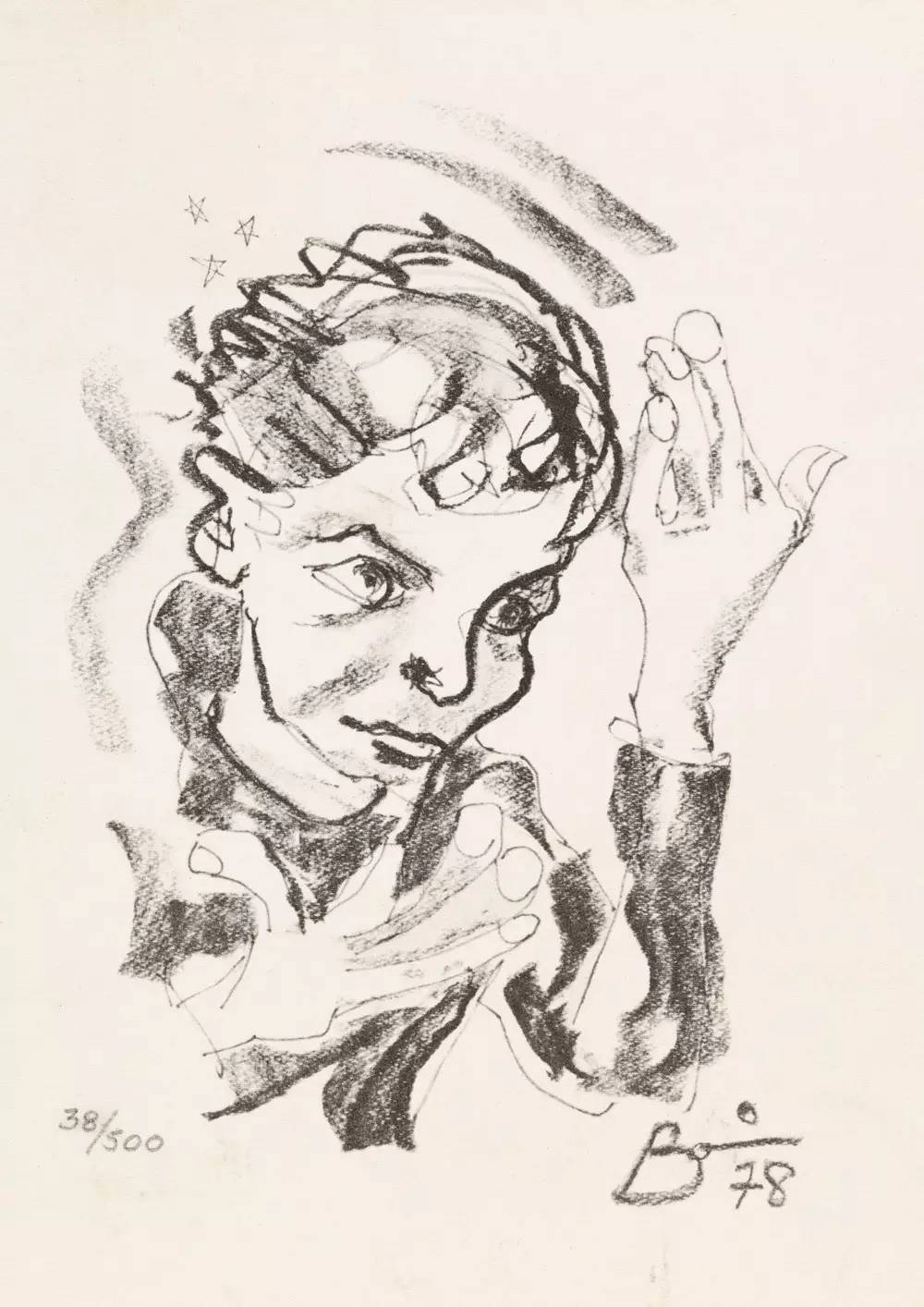

Comprising canvases painted between 1976 and 1996, the selections include not just Bowie’s self-portraits but depictions of such friends and associates as Iggy Pop, painted in Berlin in 1978 just above, and pianist Mike Garson.

Bowieologists recognize his “Berlin era” in the late 1970s, which produced the albums Low, Lodger, and “Heroes” (all to varying degrees involving the collaboration of Brian Eno) as an especially fruitful period of his musical career. But the galleries and museums of the German capital also witnessed Bowie’s first immersion into the world of visual art, both as an enthusiast and as a creator. The city even found its way into some of his paintings, such as 1977’s Child in Berlin above. “Heroes”, the final album of Bowie’s “Berlin trilogy,” even inspired a bit of Bowie artwork, the self-portrait sketch below modeled on the record’s famous cover photo by Masayoshi Sukita, itself inspired by Erich Heckel’s 1917 painting Roquairol.

But just as Bowie the musician and performer couldn’t stop seeking out and incorporating new influences, so did Bowie the painter’s attention continually turn to new subject matter, including the mythology of the tribes inhabiting present-day South Africa. At Very Private Gallery you can see not just more of his finished work but more of his sketches, including studies of Hunger City, the thematic setting of his elaborate Diamond Dogs tour as well as for a film planned, but never actually shot, in the mid-1970s. Despite the considerable difference in medium between music and images, Bowie’s visual work still comes across clearly as Bowie’s work — especially a face drawn, true to elegantly nostalgic form, on a pack of Gitanes.

Related Content:

96 Drawings of David Bowie by the “World’s Best Comic Artists”: Michel Gondry, Kate Beaton & More

The Art from David Bowie’s Final Album, Blackstar, is Now Free for Fans to Download and Reuse

David Bowie Lists His 25 Favorite LPs in His Record Collection: Stream Most of Them Free Online

The Story of Ziggy Stardust: How David Bowie Created the Character that Made Him Famous

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.