The lines of the descent from the plutocratic wealth and autocratic power of the late 19th century to the worst atrocities of the early 20th might seem apparent to some people. So too can we trace from the Gilded Age an institutional system of monuments to art, culture, and higher learning unique to modern times. Whether by virtue of greed, guilt, or noblesse oblige, or some of all of the above, wealthy industrialists sought to show—as Andrew Carnegie wrote in his “Gospel of Wealth”—that “the houses of some should be homes for all that is highest and best in literature and the arts, and for all the refinements of civilization.”

The treasures of world culture were donated back to the world, but the proud beneficence of their givers lived on in the institutions. In the case of Cleveland telegraph magnate Jeptha Wade, who was himself a daguerreotypist and portrait painter, the memory of the generous gift continues in Wade Park, home of the Fine Arts Garden and the Cleveland Museum of Art, created from his bequest.

Now, over 125 years later, Wade’s patronage lives on online. “Brace yourself for some meme-worthy Egyptian cats and gif-able Renaissance babies,” as Zachary Small jokes at Hyperallergic.

The museum has just announced its digital collection with a poignant quote from its founder declaring it an eternal donation to humankind: “The statement ‘for the benefit of all the people forever’ was written into Jeptha Wade’s 1892 deed of gift for the land on which the museum stands… reflecting its founders’ belief that museums should be places for inspiration and for creating wonder and meaning in people’s lives.”

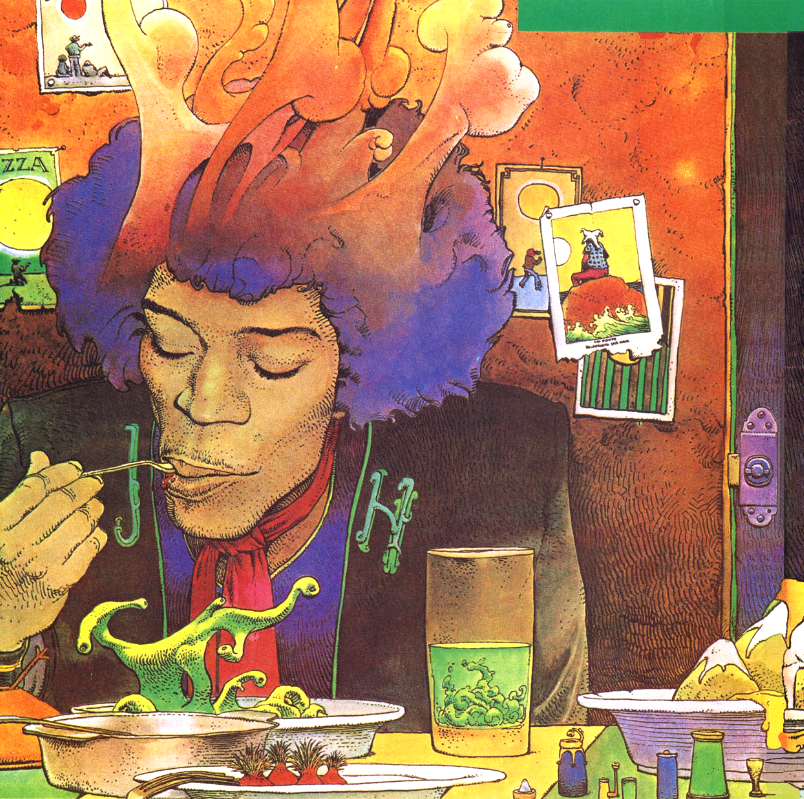

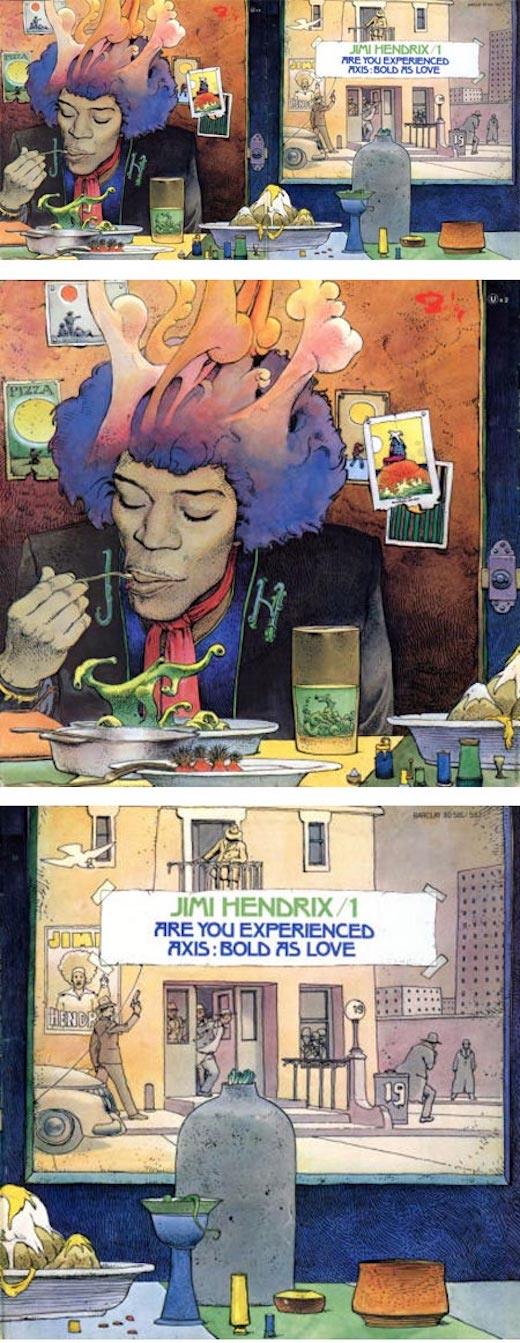

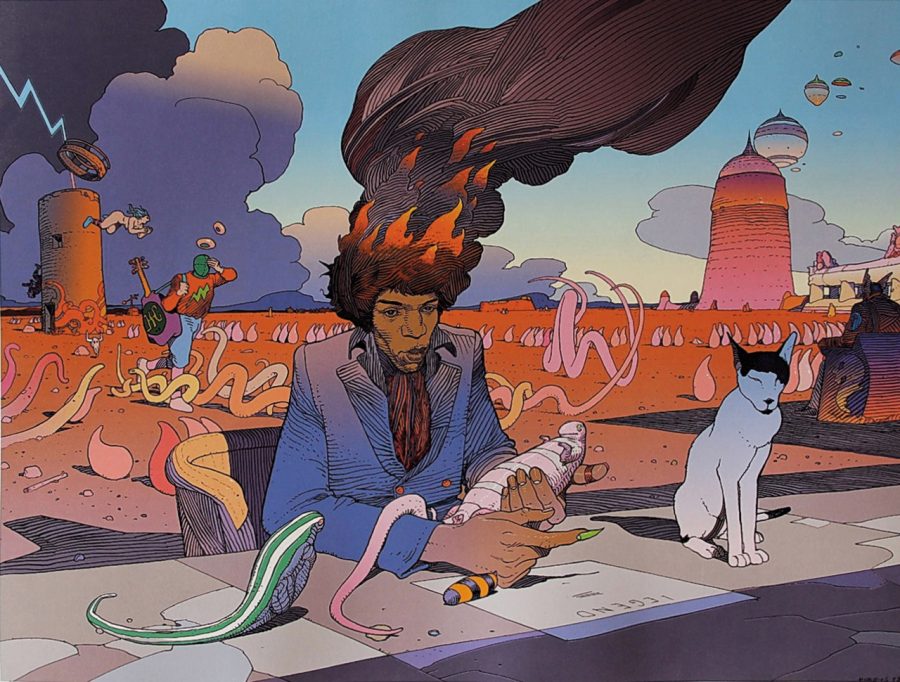

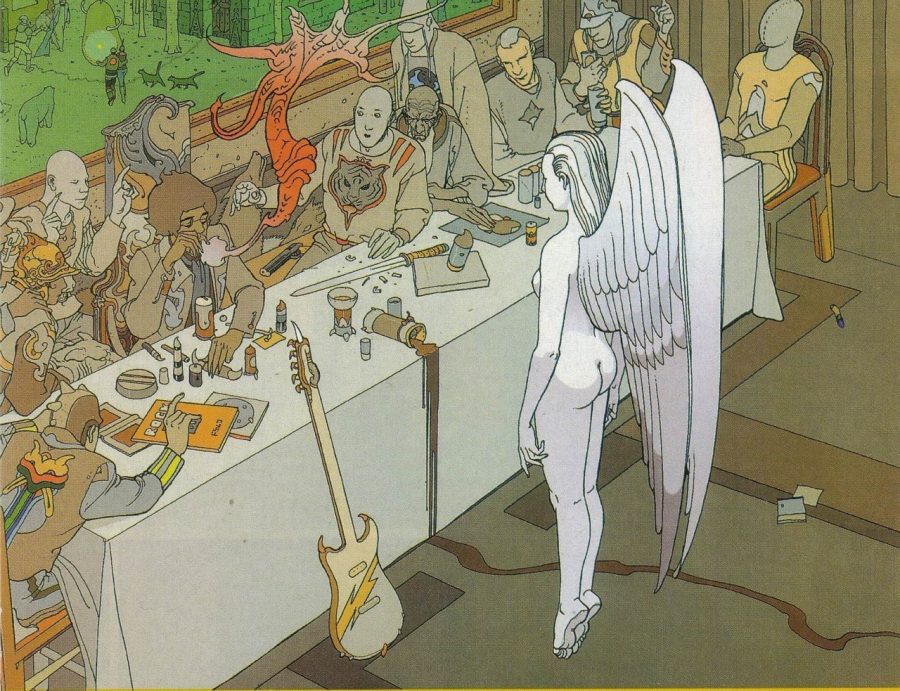

This may sound like ostentatious rhetoric, but the announcement also tells us that its free digital collection is “using Open Access,” which means “the public now has the ability to share, remix, and reuse images of as many as 30,000 CMA artworks—“nearly half of the museum’s entire collection,” notes Small—are now “in the public domain for commercial as well as scholarly and noncommercial purposes.” Take even a small sampling of their open collections and you may find more than enough inspiration, wonder, and meaning.

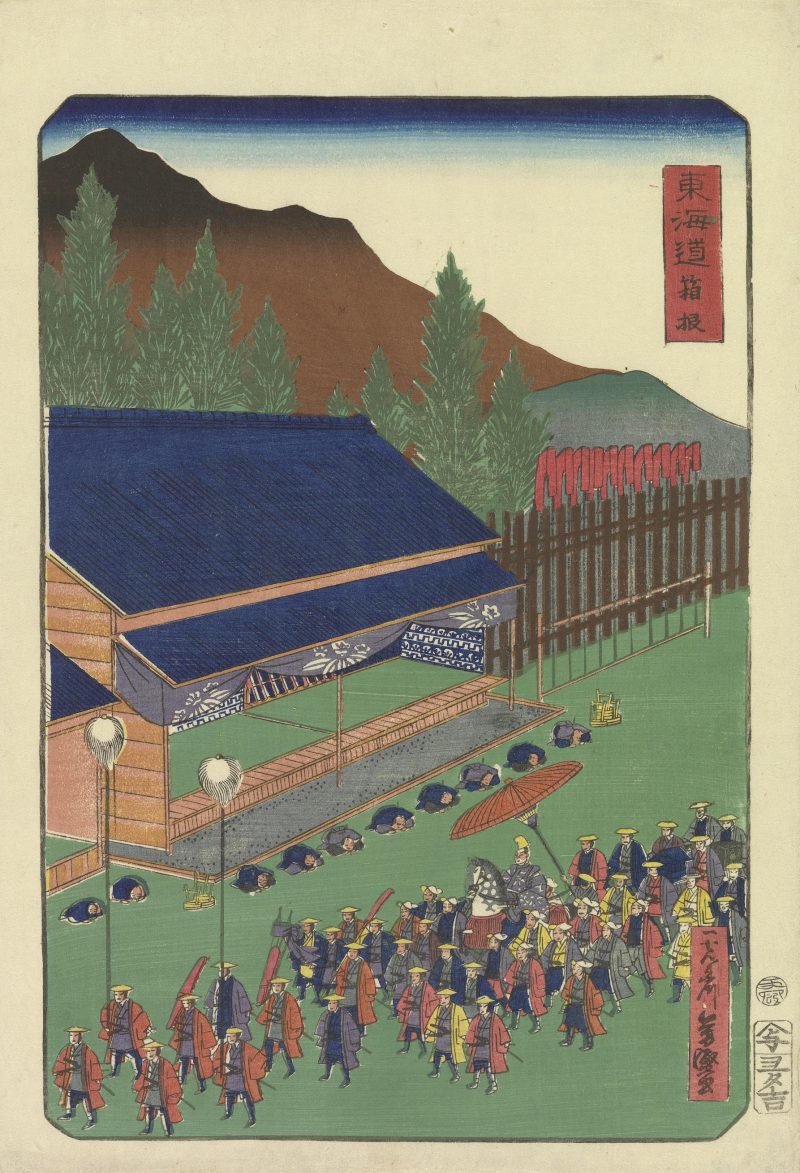

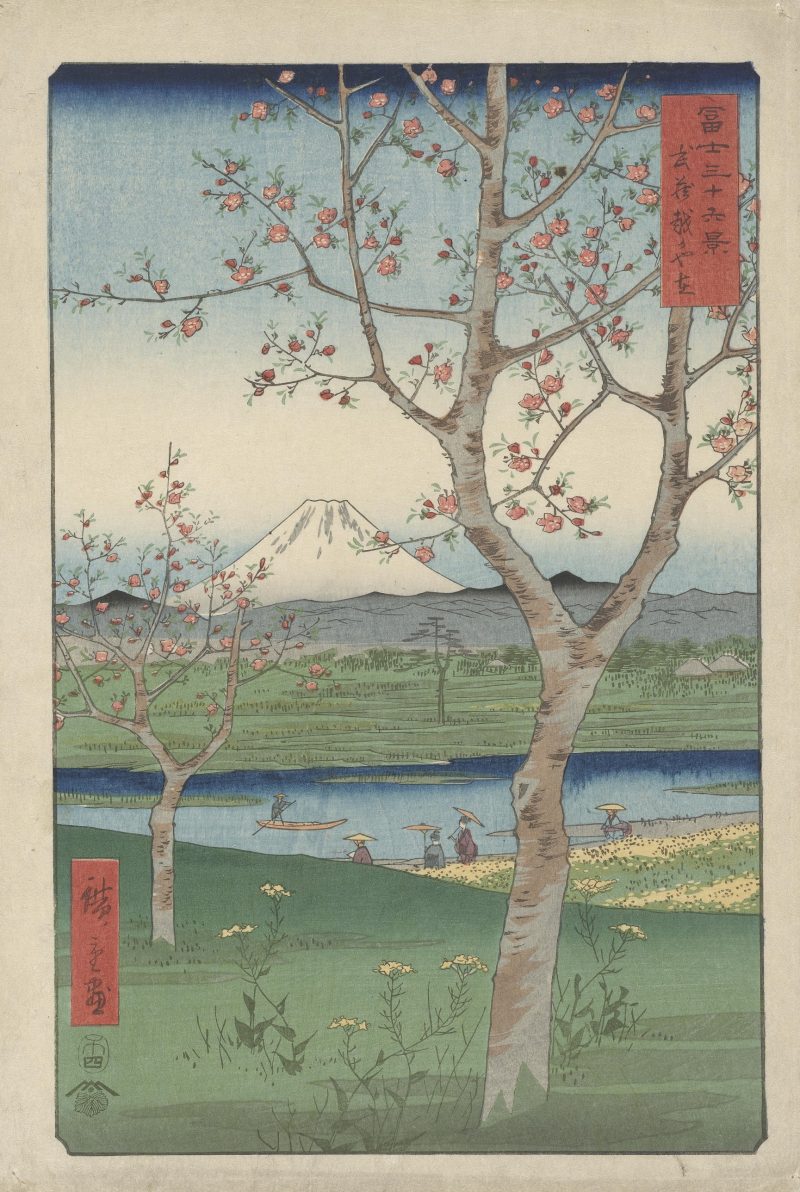

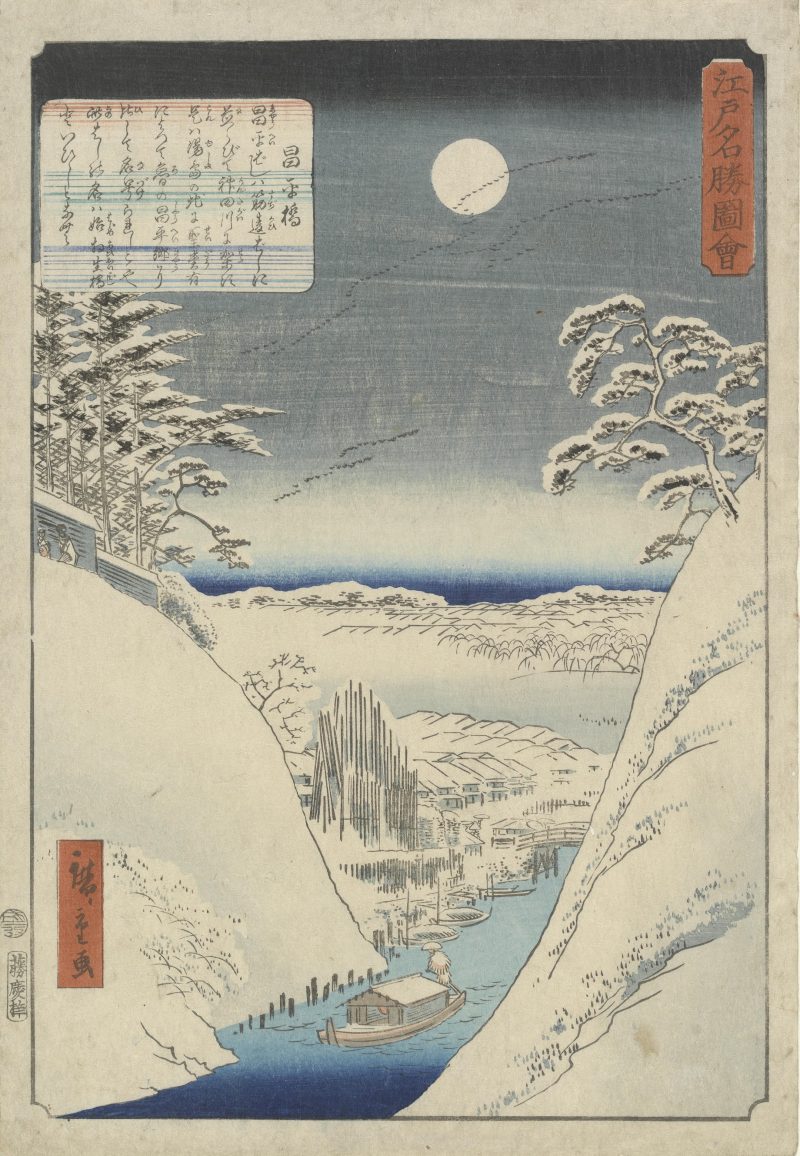

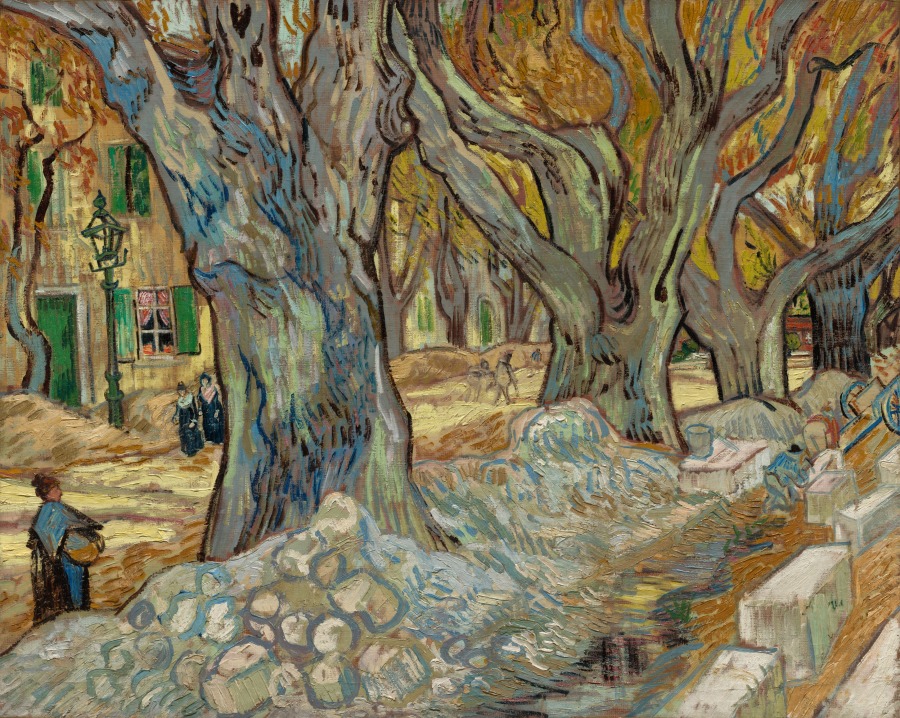

Take, for example, Van Gogh’s The Large Plane Trees, J.M.W. Turner’s The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, El Greco’s The Holy Family with Mary Magdalen, and Edouard Manet’s Berthe Morisot. Take work from Rembrandt, Velázquez, Monet, Cezanne, Caravaggio, Pissarro, Degas, Rubens, Poussin, Rodin. Take masterful works like ancient Egyptian New Kingdom Head of Amenhotep II Wearing the Blue Crown and Timurid period Iranian Royal Reception in a Landscape—as well as many from central Africa, China, India, Japan and Korea.

The Open Access collection has swelled to over 34,000 images that can be downloaded as jpgs or high-resolution tiffs. These and over 60,000 more online works come with descriptions, citations, exhibition histories, and more. Whatever confluence of historical and contemporary events brought Cleveland’s digital collection into being, it does indeed seem to be for the great benefit of a great number of internet-connected people around the world. Take full advantage of its newly public resources here.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The Art Institute of Chicago Puts 44,000+ Works of Art Online: View Them in High Resolution

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

Google Puts Over 57,000 Works of Art on the Web

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness