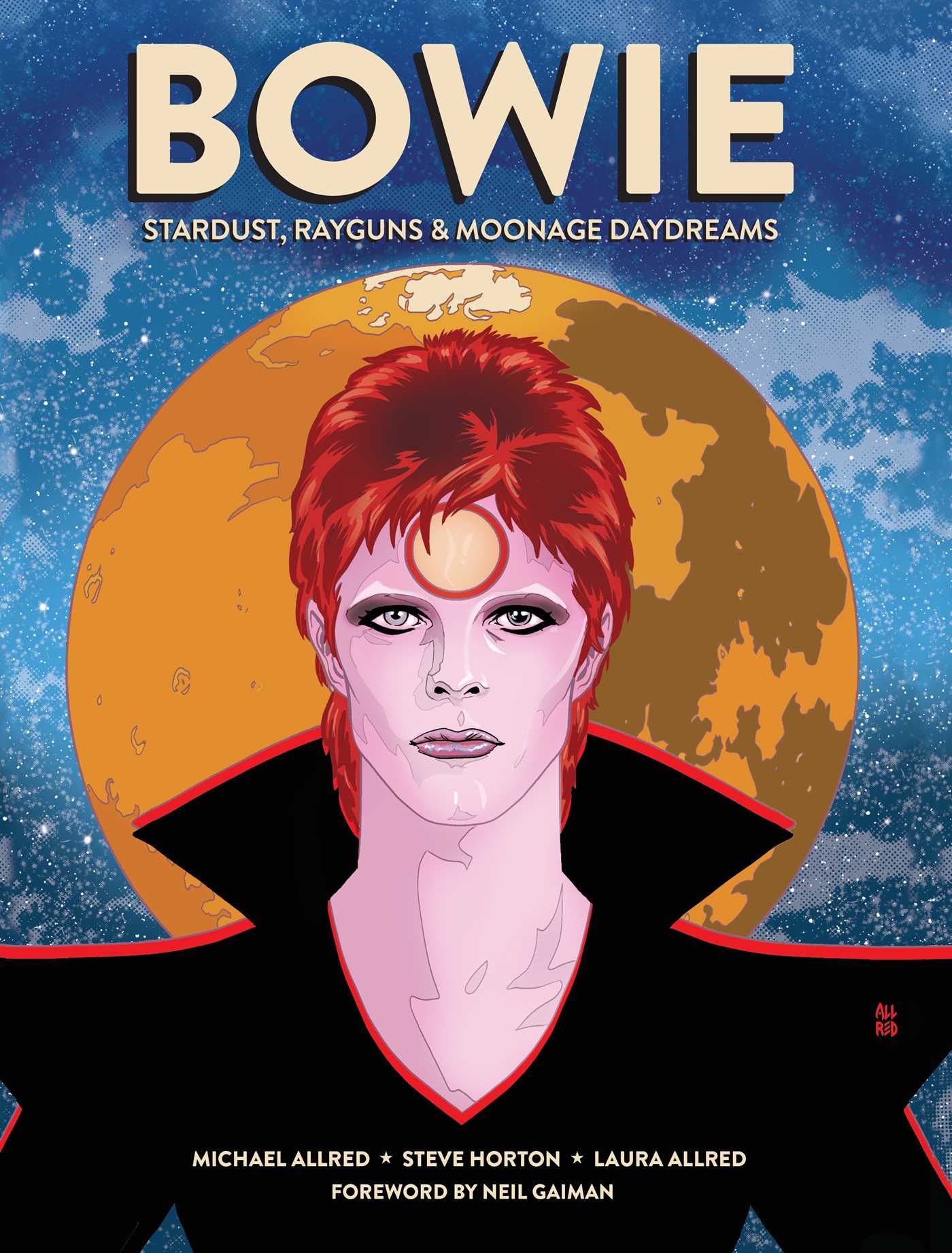

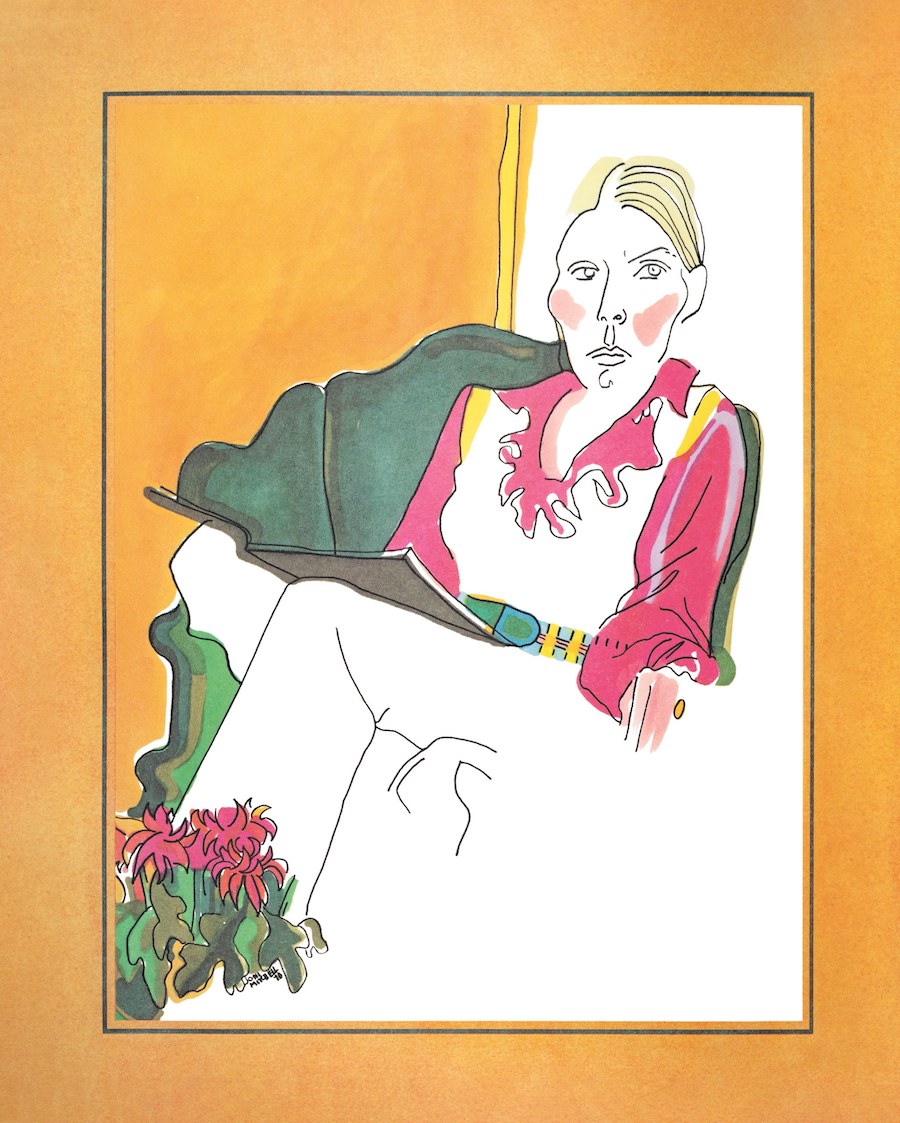

Self Portrait.”Art work by Joni Mitchell, from “Morning Glory on the Vine” / Courtesy Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Joni Mitchell is a woman of many talents—too many for the label “singer-songwriter” to encompass. It does not capture the literary depth of her lyricism, the unique strength of her distinctive voice, or the deftness and versatility of her guitar playing. Nor the fact that she’s one of the most interesting personalities in rock (or folk-rock/folk/folk-jazz, whatever). Mitchell’s biography is riveting; her chatty and cantankerous interviews a treat.

And, if you somehow didn’t know from her many album covers, Mitchell is also an accomplished visual artist. “I have always thought of myself as a painter derailed by circumstance,” she said in 2000. “I sing my sorrow and I paint my joy.” It’s a great quote, though she also sings her joy and paints sorrow—as in the portrait of her hero, Miles Davis, made just after his death. (Davis was a painter too, and they bonded over art.)

Mitchell began selling her work “when I was in high school to dentists, doctors—small time,” she told Rolling Stone in 1990. She has written poetry since her teenage years. Her imagistic songwriting came from a love of literary language. “I wrote poetry,” she says, “and I always wanted to make music. But I never put the two things together,” until she heard Dylan’s “Positively Fourth Street” and realized “you could make your songs literature.”

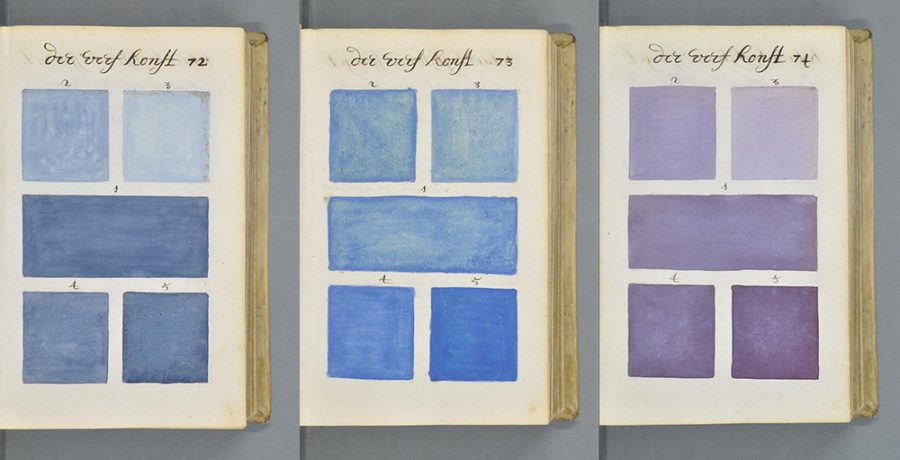

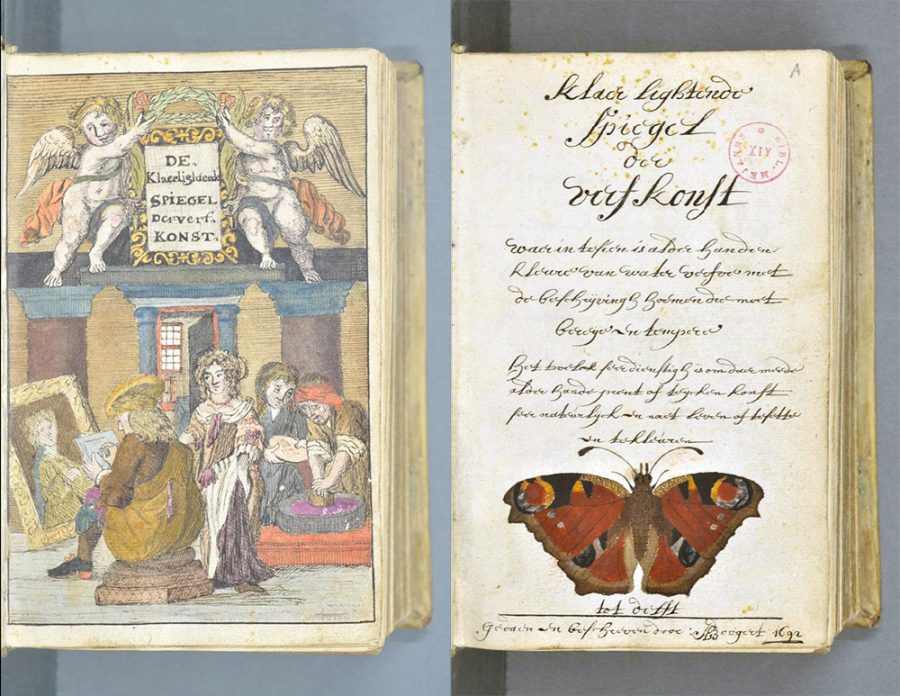

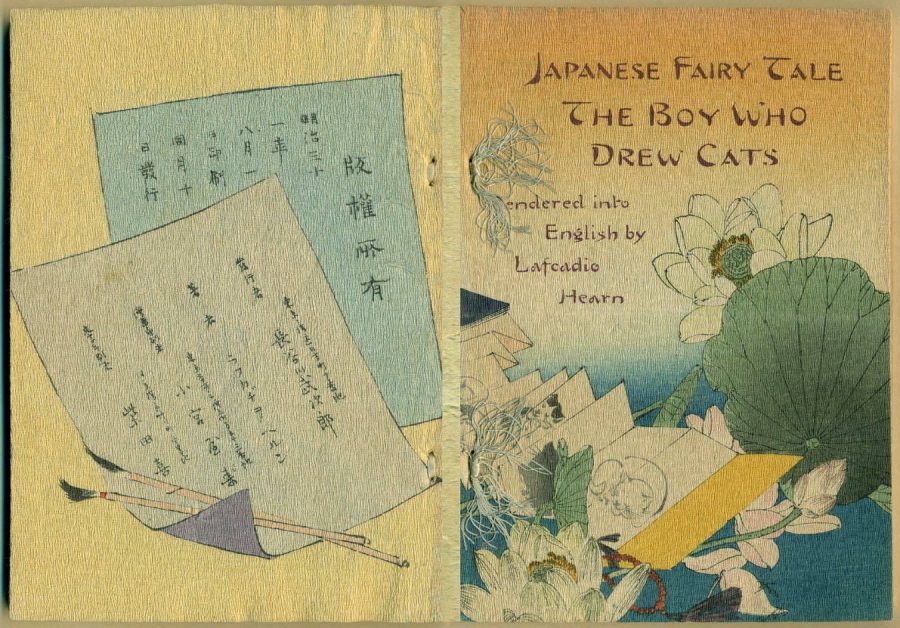

Painter, poet, singer, songwriter, guitarist—all of the artistic sides of Mitchell have mingled throughout her career in the visual splendor of her covers, compositions, and lyrics. They also came together in a rare 1971 book. After the release of Blue, Mitchell “gathered more than thirty drawings and watercolors in a ring binder and paired them with handwritten lyrics and bits of poetry,” writes Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker.

She had the book handbound in an edition of 100 copies and gave it to friends for the holidays, calling it “The Christmas Book.” Now it has a different title, Morning Glory on the Vine, for a new edition to be released October 22nd. Part of the extensive celebrations for Mitchell’s 75th birthday, this edition fulfills a decade-long desire for the artist. “I always wanted to redo it and simplify the presentation,” she tells Petrusich. “Work is meant to be seen.”

The collection “feels consonant with Mitchell’s songwriting” in that it captures “tantalizing details about home,” in this case the home in Laurel Canyon that she shared with Graham Nash, the inspiration for the Crosby, Stills & Nash song “Our House.” Still life compositions and self-portraits, both “vivid” and “intimate,” complement her vulnerable, playful, “funny and weird,” lyrics and verses. You can see more of the paintings from Morning Glory on the Vine at The New Yorker and order a copy of the book here.

Related Content:

Songs by Joni Mitchell Re-Imagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers & Vintage Movie Posters

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness