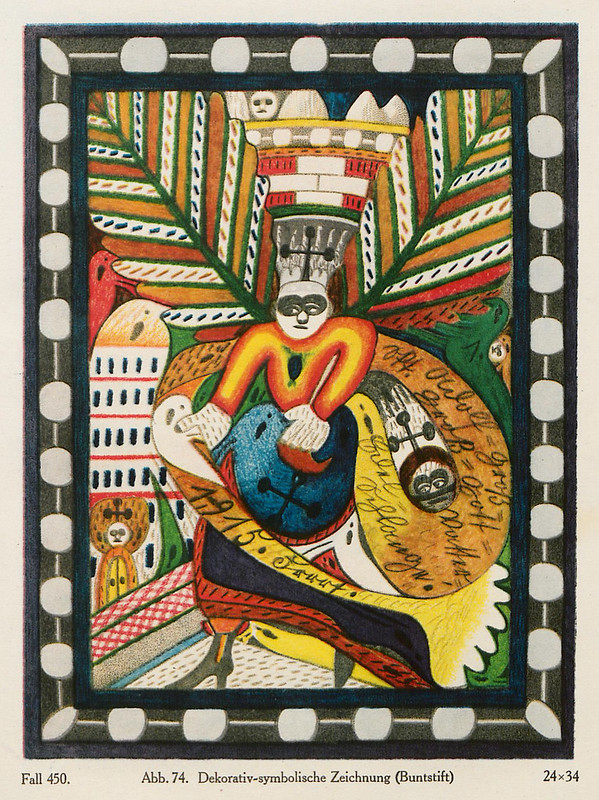

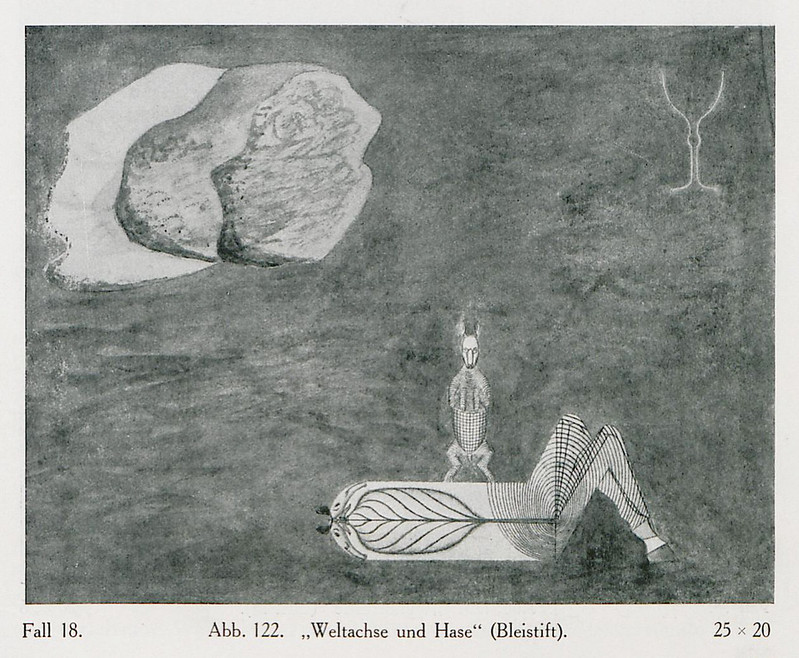

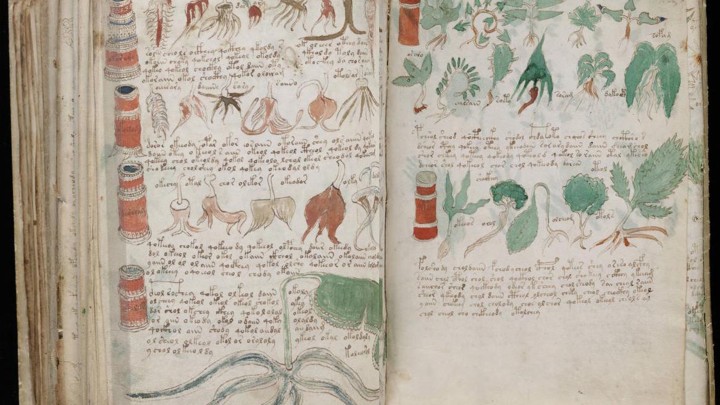

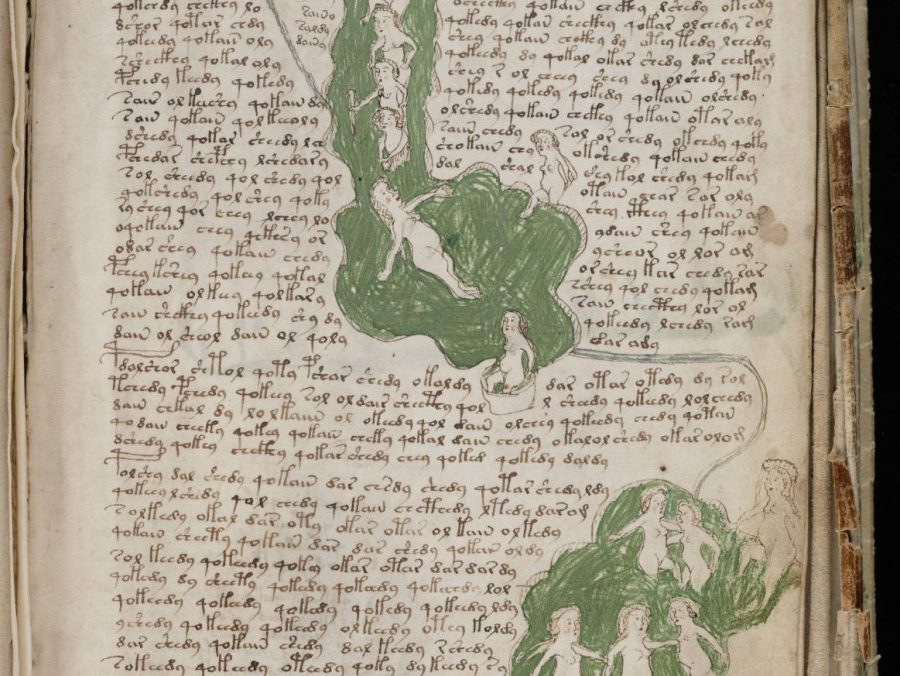

Humanity will remember the name of James Joyce for generations to come, not least because, as he once wrote about his best-known novel Ulysses, “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.” If Joyce was right, then the author of the mysterious Voynich manuscript (about which you can see an animated introduction here) has set a kind of standard for immortality. Filled with odd, not especially explanatory illustrations and written in a script not seen anywhere else, the early 15th-century text has perplexed scholars for at least 400 or so years of its existence.

But recent years have seen a few claims of having cracked the Voynich manuscript’s code: one effort made use of artificial intelligence, another concludes that the text was written in phonetic Old Turkish, and the latest declares the Voynich manuscript to have been composed in “the only known example of proto-Romance language.” University of Bristol Research Associate Gerard Cheshire, the man behind this new decoding, describes that language as “ancestral to today’s Romance languages including Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, Romanian, Catalan and Galician. The language used was ubiquitous in the Mediterranean during the Medieval period, but it was seldom written in official or important documents because Latin was the language of royalty, church and government.”

And what, pray tell, is the Voynich manuscript actually about? Cheshire has revealed little about its content thus far, though he has described the text as “compiled by Dominican nuns as a source of reference for Maria of Castile, Queen of Aragon.” Though he has claimed to determine the nature of its unusual language — one without punctuation but with “diphthong, triphthongs, quadriphthongs and even quintiphthongs for the abbreviation of phonetic components” — deciphering its more than 200 pages of content stands as another task altogether. In the meantime, you can read his paper “The Language and Writing System of MS408 (Voynich) Explained,” originally published in the journal Romance Studies.

Although Cheshire’s discovery has produced headlines like the Express’ “Voynich Manuscript SOLVED: World’s Most Mysterious Book Deciphered After 600 Years,” others include Ars Techhnica’s “No, Someone Hasn’t Cracked the Code of the Mysterious Voynich Manuscript.” That article quotes Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America (and vocal Voynich-translation skeptic), criticizing the foundation of Cheshire’s claim: “He starts with a theory about what a particular series of glyphs might mean, usually because of the word’s proximity to an image that he believes he can interpret. He then investigates any number of medieval Romance-language dictionaries until he finds a word that seems to suit his theory. Then he argues that because he has found a Romance-language word that fits his hypothesis, his hypothesis must be right.”

Fagin Davis adds that Cheshire’s “ ‘translations’ from what is essentially gibberish, an amalgam of multiple languages, are themselves aspirational rather than being actual translations,” and that “the fundamental underlying argument — that there is such a thing as one ‘proto-Romance language’ — is completely unsubstantiated and at odds with paleolinguistics.” Fagin Davis’ criticism doesn’t even stop there, and if she’s right, Cheshire’s approach will be unlikely to produce a coherent translation of the entire text. And so, at least for the moment, the Voynich manuscript’s life as a mystery continues, keeping busy not just professors but enthusiasts, technologists, Research Associates, and many others besides.

Related Content:

An Introduction to the Codex Seraphinianus, the Strangest Book Ever Published

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.