In 1919, German architect Walter Gropius founded Bauhaus, the most influential art school of the 20th century. Bauhaus defined modernist design and radically changed our relationship with everyday objects. Gropius wrote in his manifesto Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar that “There is no essential difference between the artist and the artisan.” His new school, which featured faculty that included the likes of Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Josef Albers and Wassily Kandinsky, did indeed erase the centuries-old line between applied arts and fine arts.

Bauhaus architecture sandblasted away the ornate flourishes common with early 20th century buildings, favoring instead the clean, sleek lines of industrial factories. Designer Marcel Breuer reimagined the common chair by stripping it down to its most elemental form.

Herbert Bayer reinvented and modernized graphic design by focusing on visual clarity. Gunta Stölzl, Marianne Brandt and Christian Dell radically remade such diverse objects as fabrics and tea kettles.

Nowadays, of course, getting one of those Bauhaus tea kettles, or even an original copy of Gropius’s manifesto, would cost a small fortune. Fortunately for design nerds, typography mavens and architecture enthusiasts everywhere, the good folks over at Monoskop have posted online a whole set of beautifully designed publications from the storied school.

Click here to pick out individual works or here to just get all of them. Sadly, though, you can’t download a teakettle.

The list of Books in the Monoskop Bauhaus archive includes:

- 1. Walter Gropius (ed.), Internationale Architektur, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925.

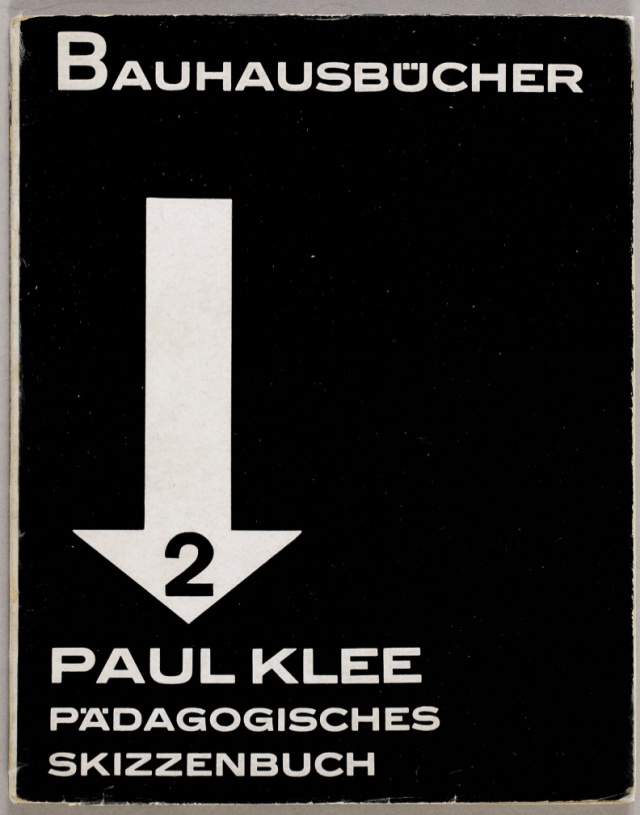

- 2. Paul Klee, Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 50 pp.

- Pedagogical Sketchbook, intro. & trans. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1953 (in English)

- Παιδαγωγικό Σημειωματάριο, trans. Β. Λαγοπούλου, 1976. (in Greek)

- Pedagogikheskie eskizy, trans. N. Druzhkovoy, 2005. (in Russian)

- 3. Adolf Meyer (ed.), Ein Versuchshaus des Bauhauses in Weimar, Munich: Albert Langen, 1924.

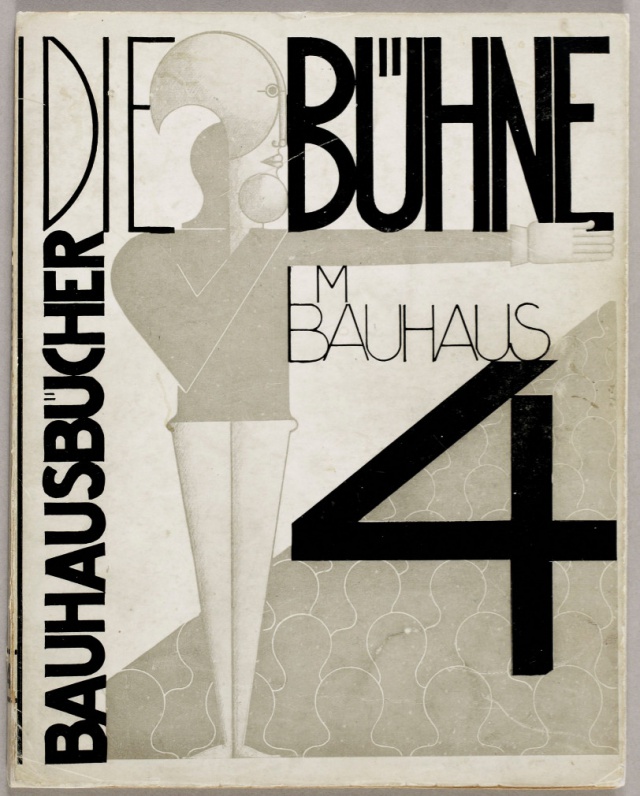

- 4. Die Bühne am Bauhaus, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925.

- The Theater of the Bauhaus, trans. Arthur S. Wensinger, Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1961. (in English)

- 5. Piet Mondrian, Neue Gestaltung, Neoplastizimus, Nieuwe Beelding, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925.

- 6. Theo van Doesburg, Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925.

- Principles of Neo-Plastic Art, London: Lund Humphries, 1969. (in English)

- 7. Walter Gropius (ed.), Neue Arbeiten der Bauhauswerkstäffen, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925.

- 8. L. Moholy-Nagy, Malerei, Fotografie, Film, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 115 pp; 2nd ed., 1927, 140 pp. Incl. “Dynamik der Gross-Stadt.”

- Painting Photography Film, trans. Janet Seligman, London: Lund Humphries, 1969. (in English)

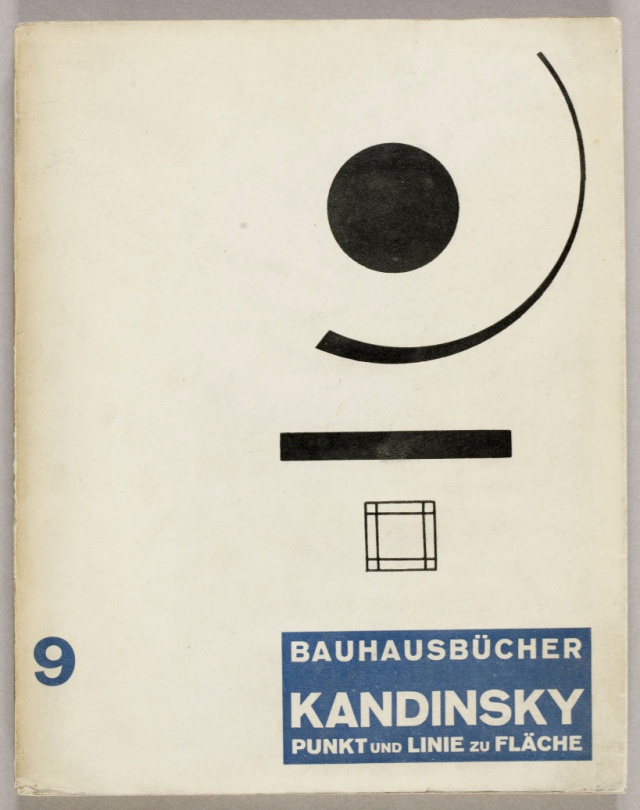

- 9. Kandinsky, Punkt und Linie zu Fläche: Beitrag zur Analyse der malerischen Elemente, Munich: Albert Langen, 1926.

- Point and Line to Plane: Contribution to the Analysis of the Pictorial Elements, trans. Howard Dearstyne and Hilla Rebay, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1947, 200 pp. (in English)

- 10. J.J.P. Oud, Holländische Architektur, Munich: Albert Langen, 1929.

- 11. Kasimir Malewitsch, Die gegenstandslose Welt, Munich: Albert Langen, 1927.

- 12. Walter Gropius, Bauhausbauten Dessau, Munich: Albert Langen, 1930.

- 13. Albert Gleizes, Kubismus, Munich: Albert Langen, 1928.

- 14. László Moholy-Nagy, Von Material zur Architektur, Munich: Albert Langen, 1929, 241 pp; facsimile repr., Mainz and Berlin: Florian Kupferberg, 1968.

- The New Vision: From Material to Architecture, trans. Daphne M. Hoffman, New York: Breuer Warren and Putnam, 1930; exp.rev.ed. as The New Vision and Abstract of an Artist, New York: George Wittenborn, 1947, 92 pp. (in English)

And here are some key Bauhaus journals:

- bauhaus 1 (1926). 5 pages, 42 cm. Download (23 MB).

- bauhaus: zeitschrift für bau und gestaltung 2:1 (Feb 1928). Download (17 MB).

- bauhaus: zeitschrift für gestaltung 3:1 (Jan 1929). Download (17 MB).

- bauhaus: zeitschrift für gestaltung 3:2 (Apr-Jun 1929). Download (15 MB).

- bauhaus: zeitschrift für gestaltung 3:3 (Jul-Sep 1929). Download (16 MB).

- bauhaus: zeitschrift für gestaltung 2 (Jul 1931). Download (15 MB).

Get more in the Monoskop Bauhaus archive.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015. We’re bringing it back to celebrate the founding of the Bauhaus school 100 years ago–on April 1, 1919.

Related Content:

Harvard Puts Online a Huge Collection of Bauhaus Art Objects

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.