There are still several ancient languages modern scholars cannot decipher, like Minoan hieroglyphics (called Linear A) or Khipu, the intricate Incan system of writing in knots. These symbols contain within them the wisdom of civilizations, and there’s no telling what might be revealed should we learn to translate them. Maybe scholars will only find accounting logs and inventories, or maybe entirely new ways of perceiving reality. When it comes, however, to a singularly indecipherable text, the Voynich Manuscript, the language it contains encodes the wisdom of a solitary intelligence, or an obscure, hermitic community that seems to have left no other trace behind.

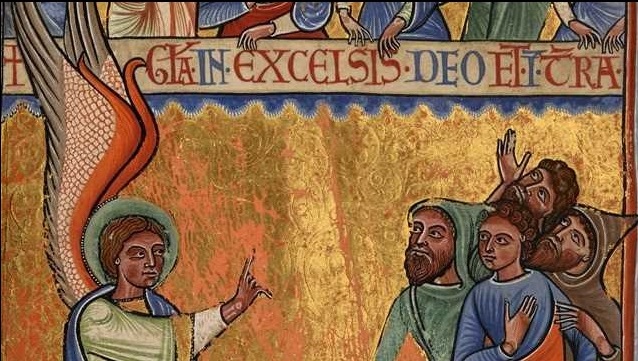

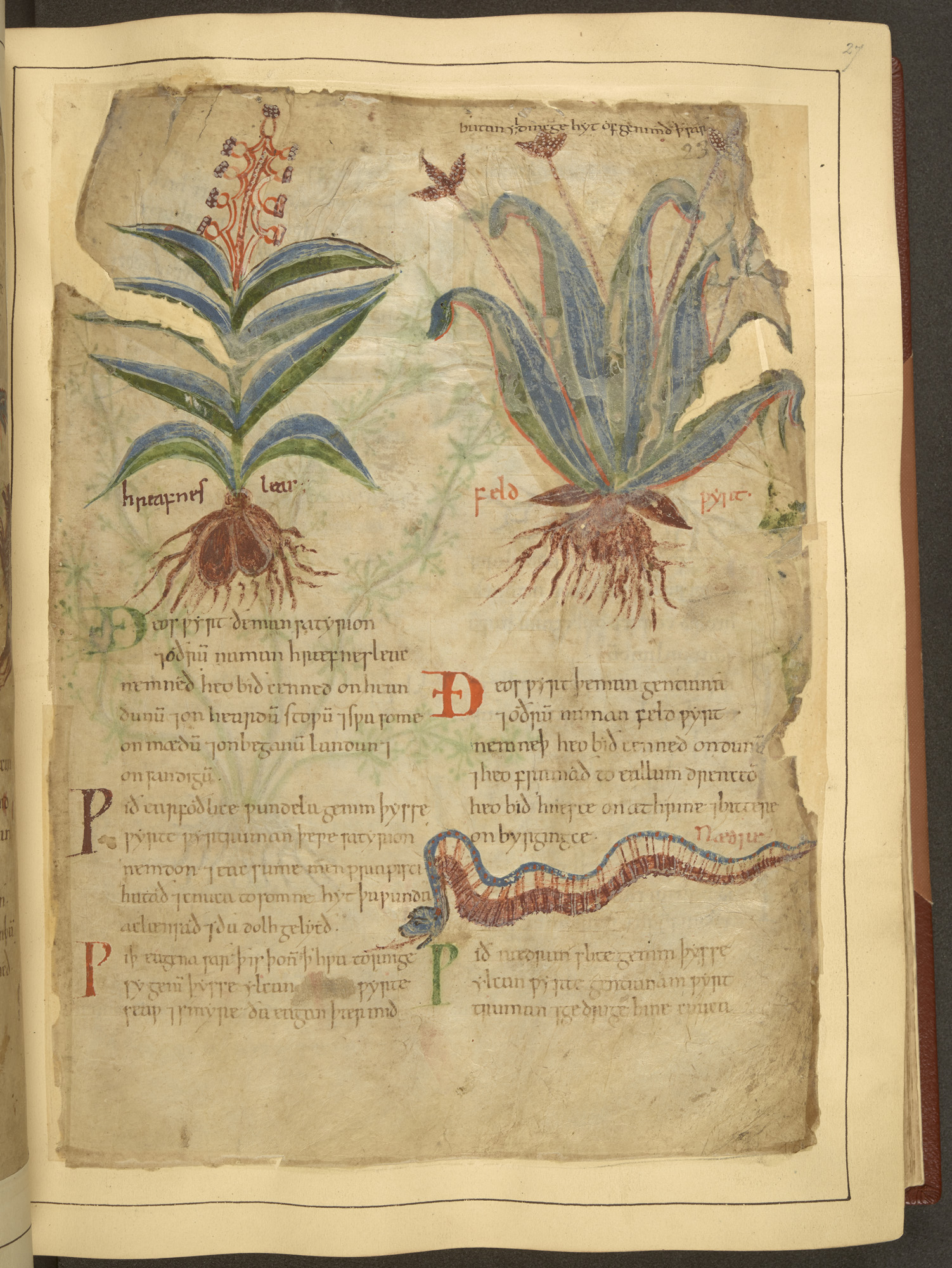

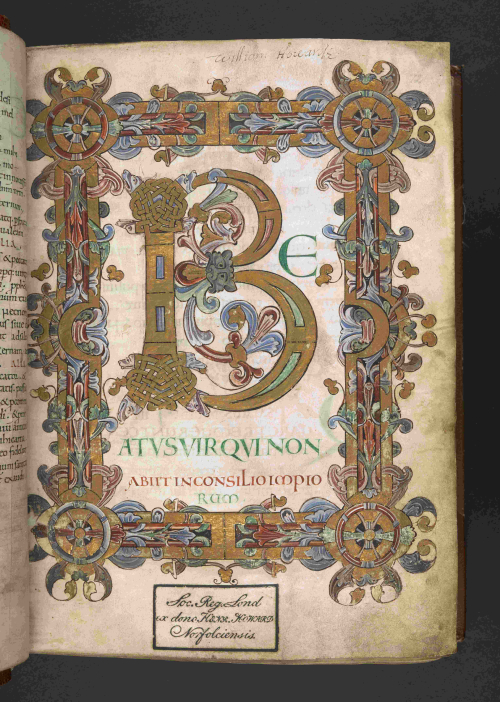

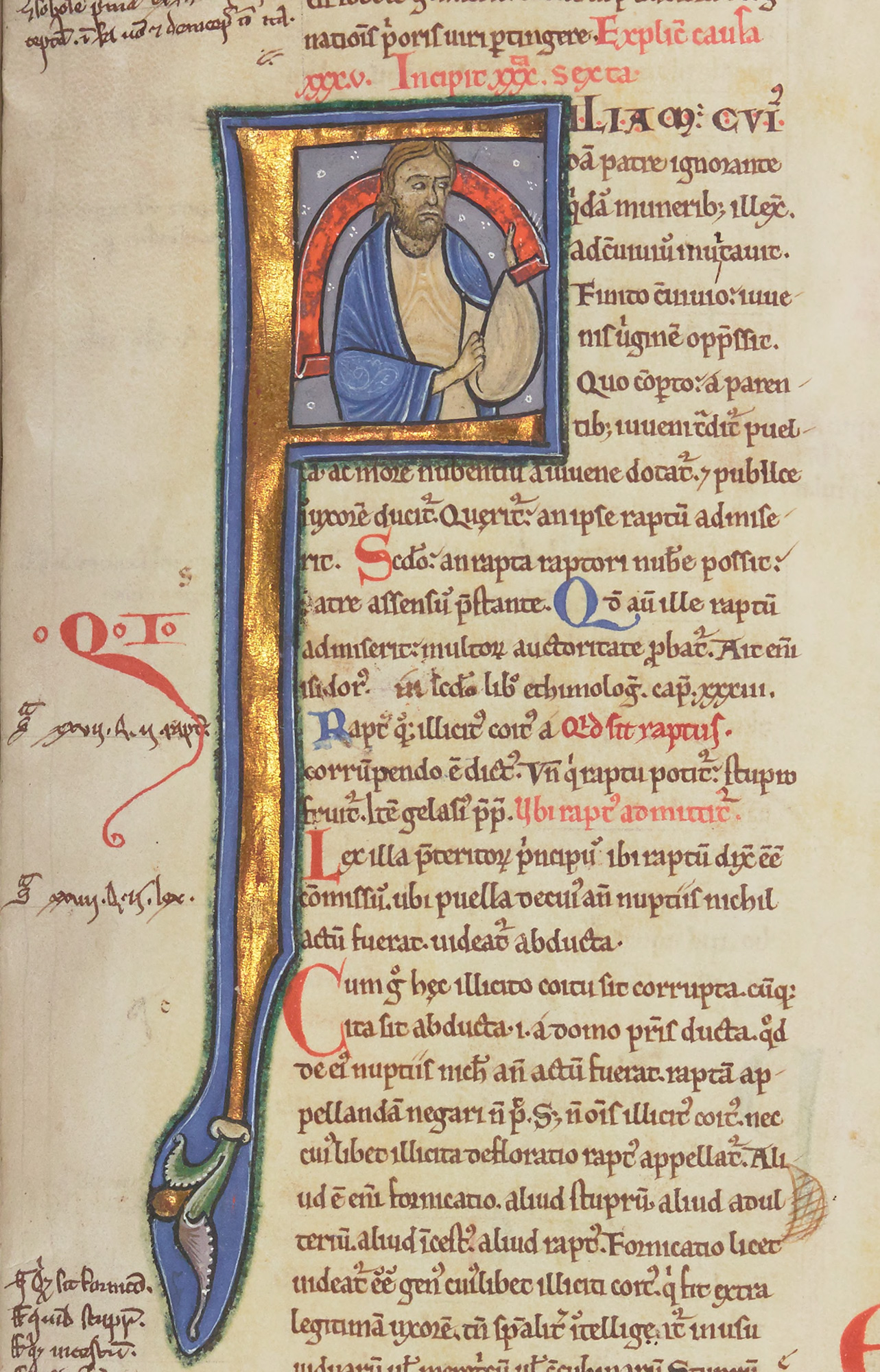

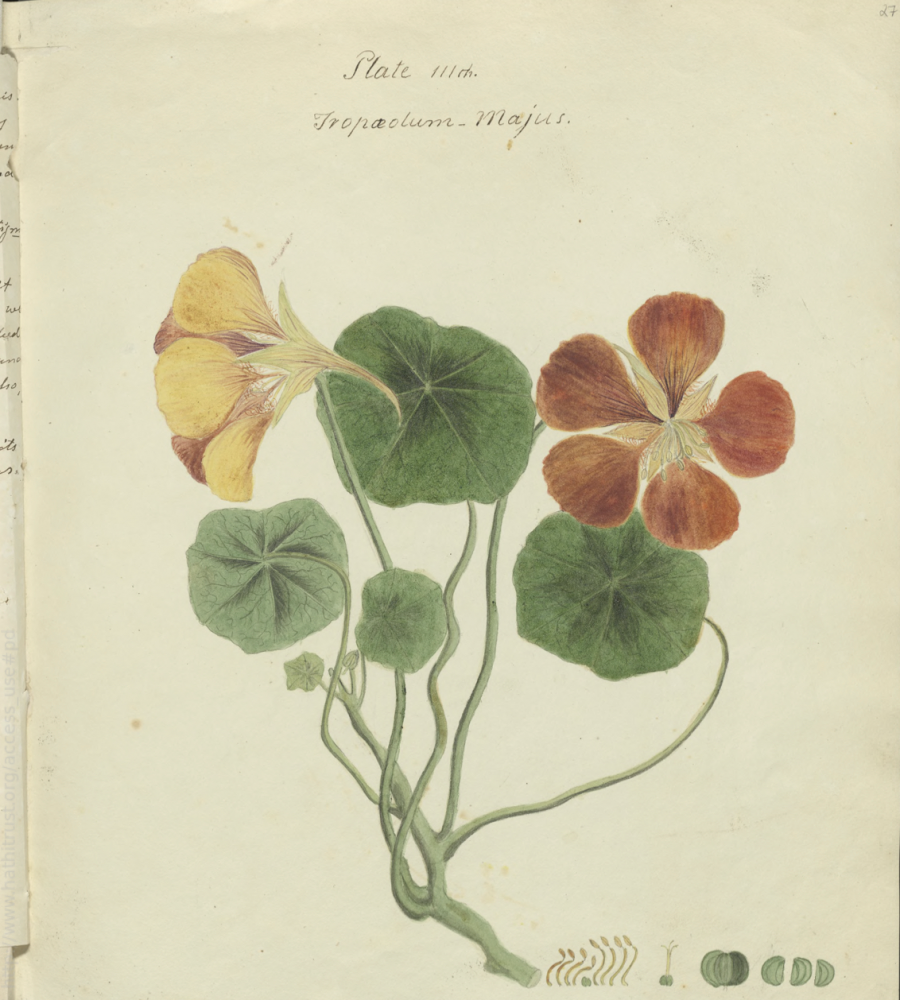

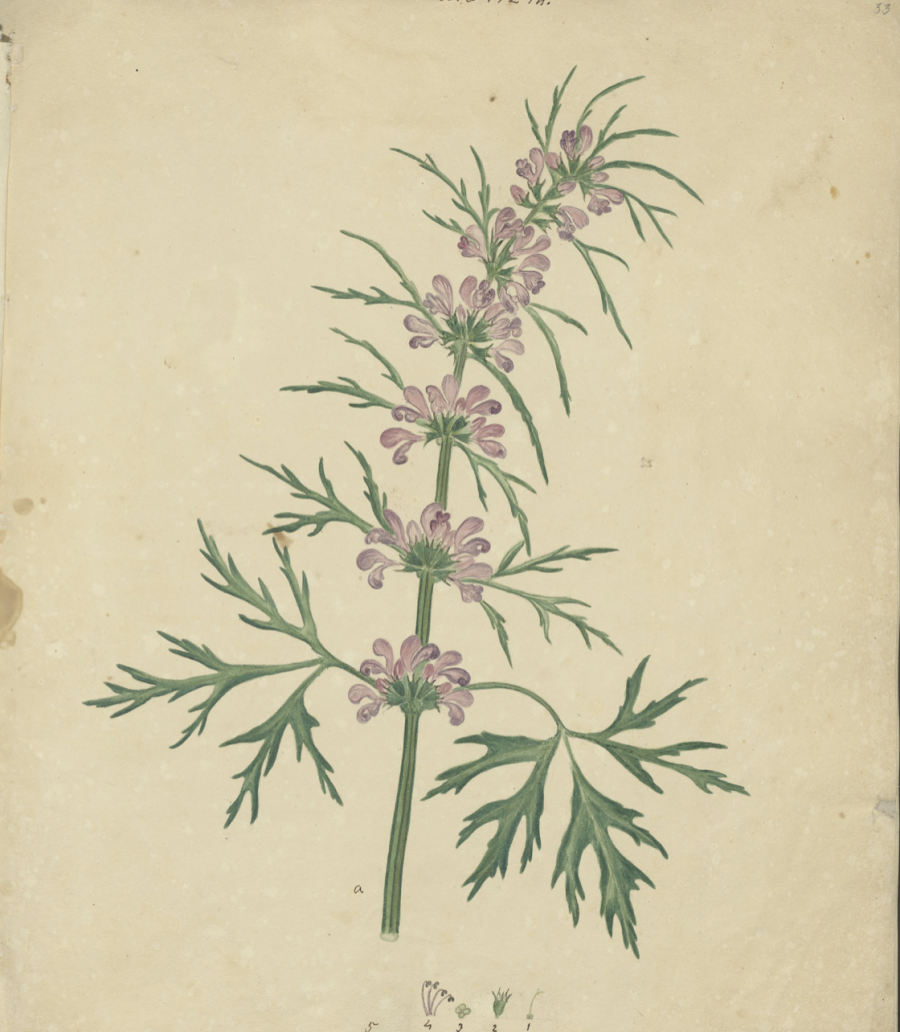

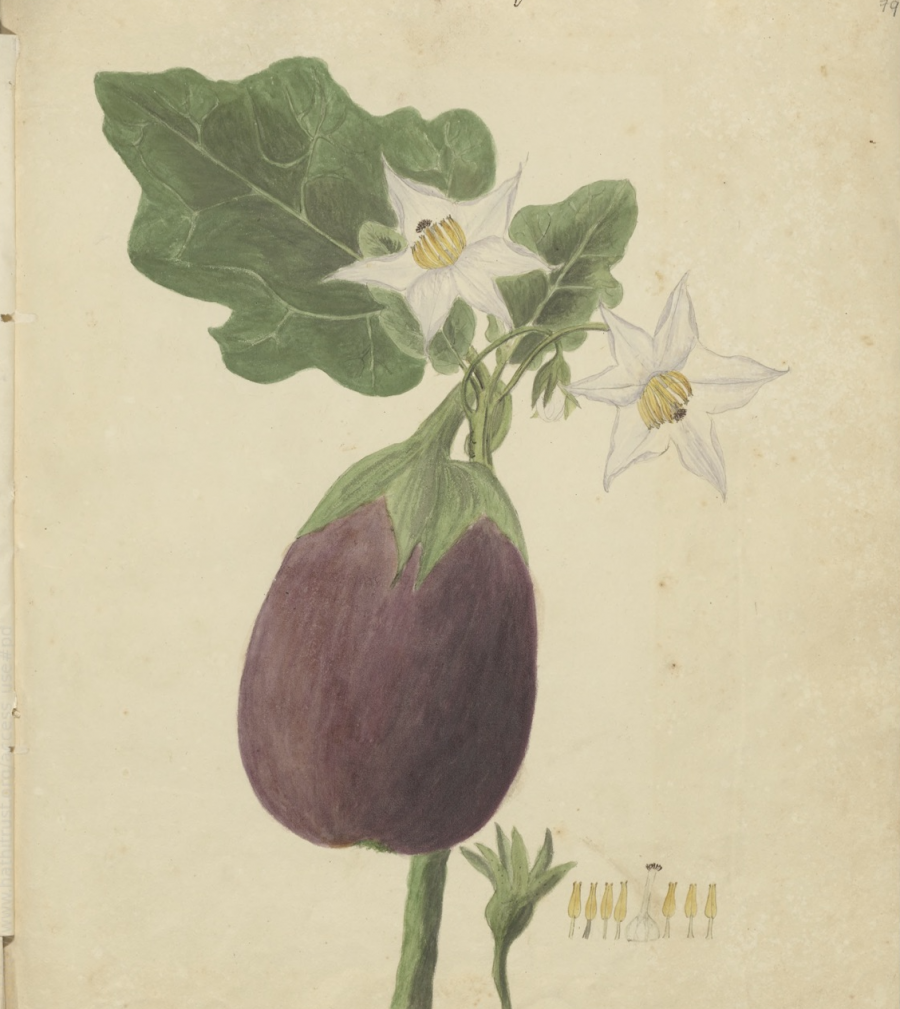

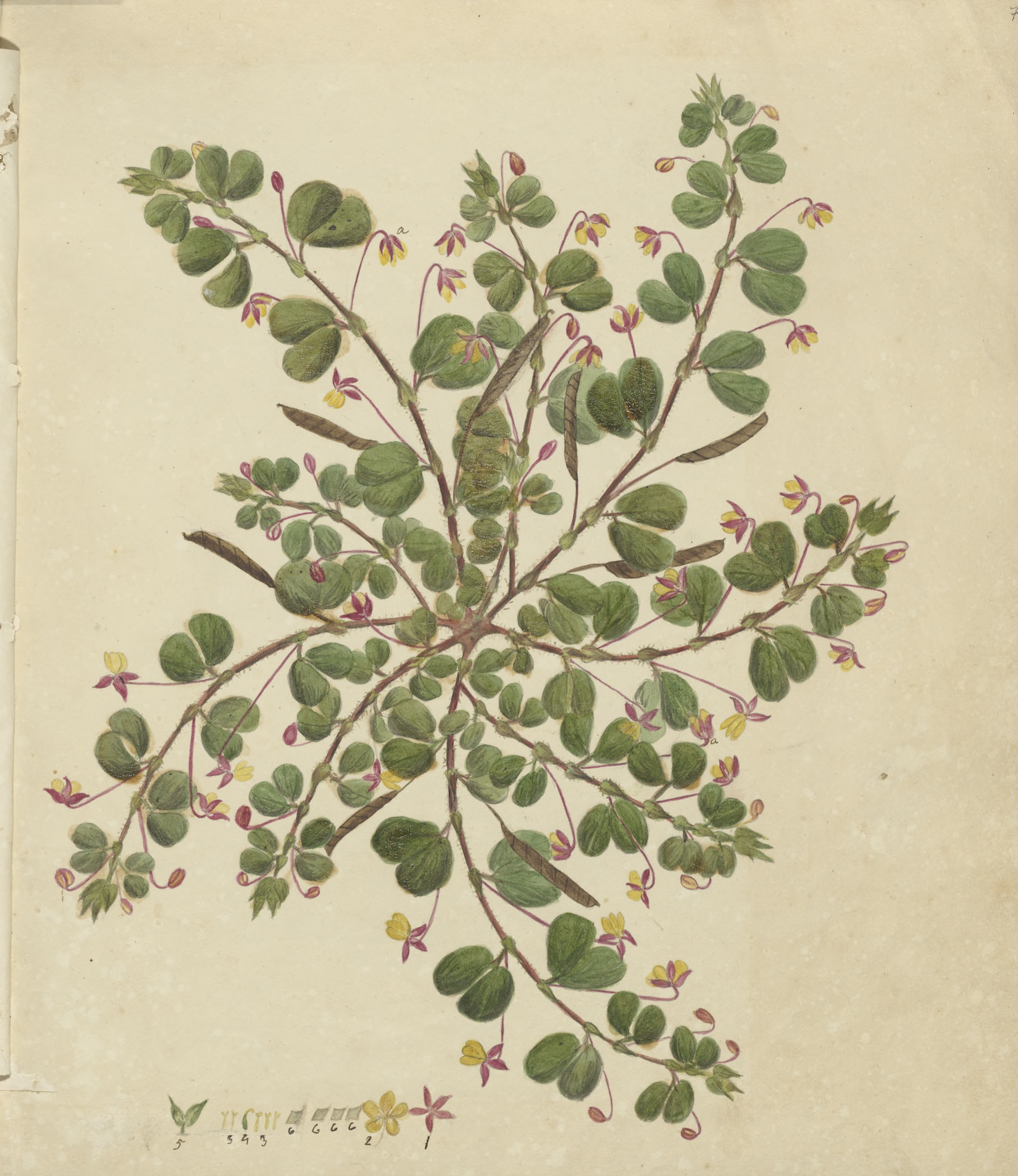

Composed around the year 1420, the 240-page manuscript appears to be in dialogue with medieval medical and alchemical texts of the time, with its zodiacs and illustrations botanical, pharmaceutical, and anatomical. But its script only vaguely resembles known European languages.

So it has seemed for the 300 years during which scholars have tried to solve its riddles, assuming it to be the work of mystics, magicians, witches, or hoaxers. Its language has been variously said to come from Latin, Sino-Tibetan, Arabic, and ancient Hebrew, or to have been invented out of whole cloth. None of these theories (the Hebrew one proposed by Artificial Intelligence) has proven conclusive.

Maybe that’s because everyone’s got the basic approach all wrong, seeing the Voynich’s script as a written language rather than a phonetic transliteration of speech. So says the Ardiç family, a father and sons team of Turkish researchers who call themselves Ata Team Alberta (ATA) and claim in the video above to have “deciphered and translated over 30% of the manuscript.” Father Ahmet Ardiç, an electrical engineer by trade and scholar of Turkish language by passionate calling, claims the Voynich script is a kind of Old Turkic, “written in a ‘poetic’ style,” notes Nick Pelling at the site Cipher Mysteries, “that often displays ‘phonemic orthography,’” meaning the author spelled out words the way he, or she, heard them.

Ahmet noticed that the words often began with the same characters, then had different endings, a pattern that corresponds with the linguistic structure of Turkish. Furthermore, Ozan Ardiç informs us, the language of the Voynich has a “rhythmic structure,” a formal, poetic regularity. As for why scholars, and computers, have seen so many other ancient languages in the Voynich, Ahmet explains, “some of the Voynich characters are also used in several proto-European and early Semitic languages.” The Ardiç family will have their research vetted by professionals. They’ve submitted a formal paper to an academic journal at Johns Hopkins University.

Their theory, as Pelling puts it, may be one more “to throw onto the (already blazing) hearth” of Voynich speculation. Or it may turn out to be the final word on the translation. Prominent Medieval scholar Lisa Fagin Davis, head of the Medieval Academy of America—who has herself cast doubt on another recent translation attempt—calls the Ardiçs’ work “one of the few solutions I’ve seen that is consistent, is repeatable, and results in sensical text.”

We don’t learn many specifics of that text in the video above, but if this effort succeeds, and it seems promising, we could see an authoritative translation of the Voynich, though there will still remain many unanswered questions, such as who wrote this strange, sometimes fantastical manuscript, and to what end?

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness