The University of California Press e‑books collection holds books published by UCP (and a select few printed by other academic presses) between 1982–2004. The general public currently has access to 770 books through this initiative. The collection is dynamic, with new titles being added over time.

Readers looking to see what the collection holds can browse by subject. The curators of the site have kindly provided a second browsing page that shows only the publicly accessible books, omitting any frustrating off-limits titles.

The collection’s strengths are in history (particularly American history and the history of California and the West); religion; literary studies; and international studies (with strong selections of Middle Eastern Studies, Asian Studies, and French Studies titles).

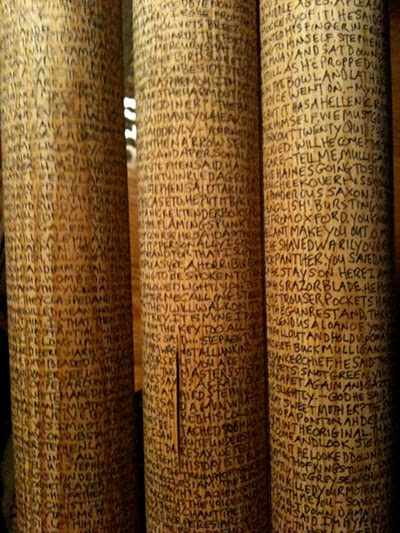

A quick browse yields a multitude of interesting possibilities for future reading: Shelley Streeby’s 2002 book about sensational literature and dime novels in the nineteenth-century United States; Luise White’s intriguing-looking Speaking with Vampires: Rumor and History in Colonial Africa (2000); and Karen Lystra’s 2004 re-examination of Mark Twain’s final years. (The image above comes from another Twain text by Randall Knoper.) Two other noteworthy texts include Roland Barthes’ Incidents and Hugh Kenner’s Chuck Jones: A Flurry of Drawings.

Sadly, you can’t download the books to an e‑reader or tablet. Happily, there is a “bookbag” function that you can use to store your titles, if you need to leave the site and come back.

As always, we’d encourage you to visit our collection of 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices, where we recently added texts by Vladimir Nabokov, Philip K. Dick and others. Also find free courses in our list of 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Rebecca Onion is a writer and academic living in Philadelphia. She runs Slate.com’s history blog, The Vault. Follow her on Twitter:@rebeccaonion.

Related Content:

Free: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Offer 474 Free Art Books Online

Read 18 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

Download 14 Great Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books and Free eBooks

Download 20 Popular High School Books Available as Free eBooks & Audio Books