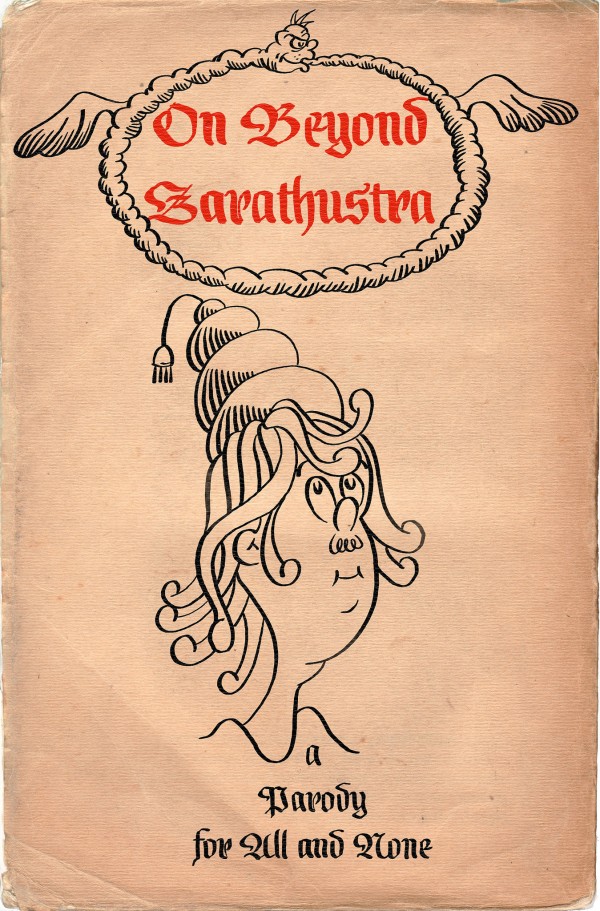

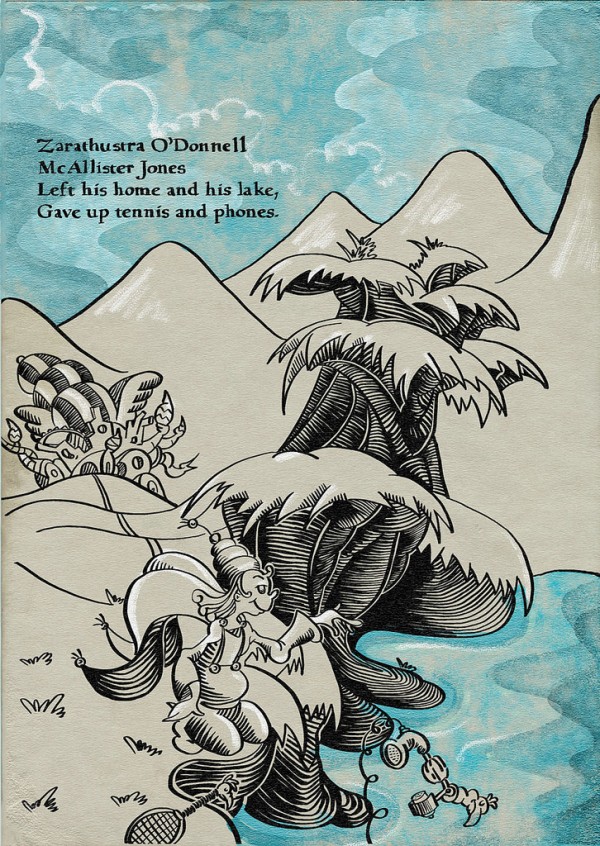

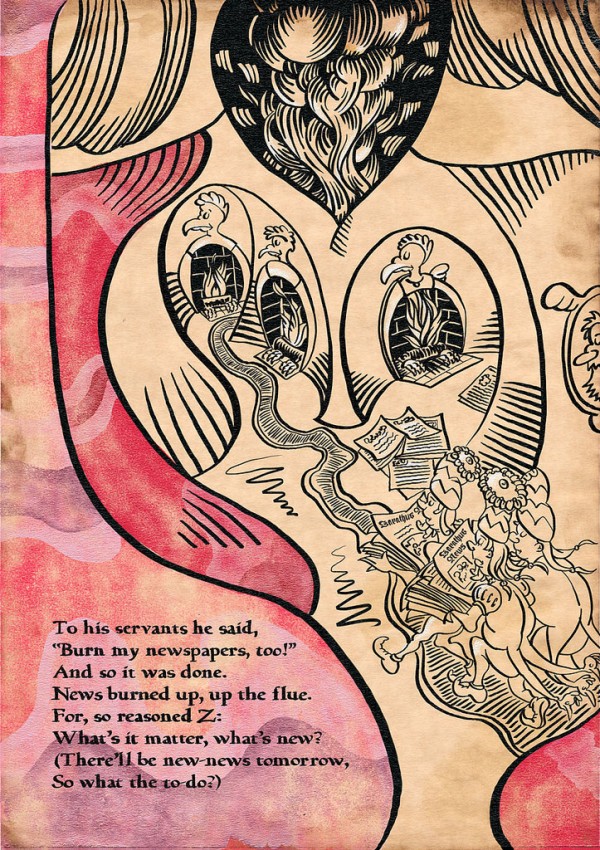

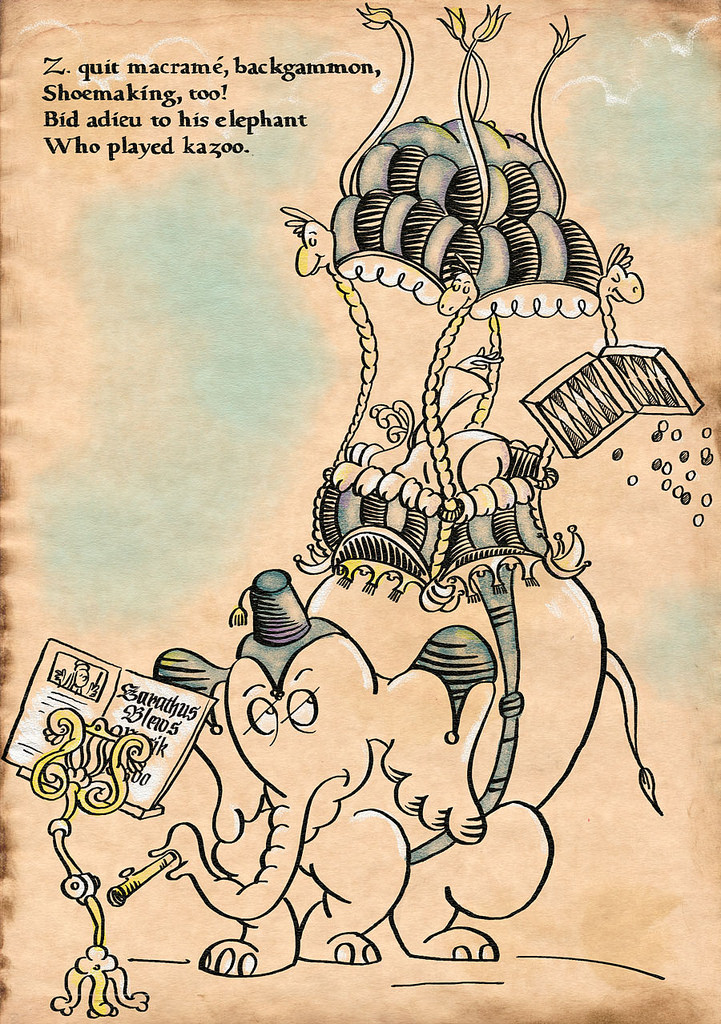

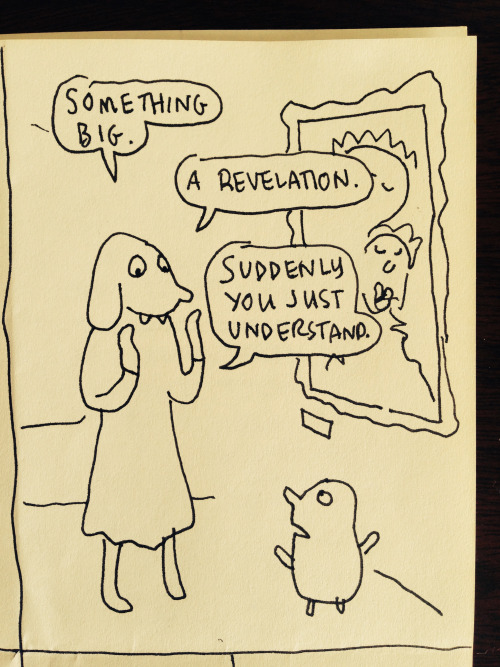

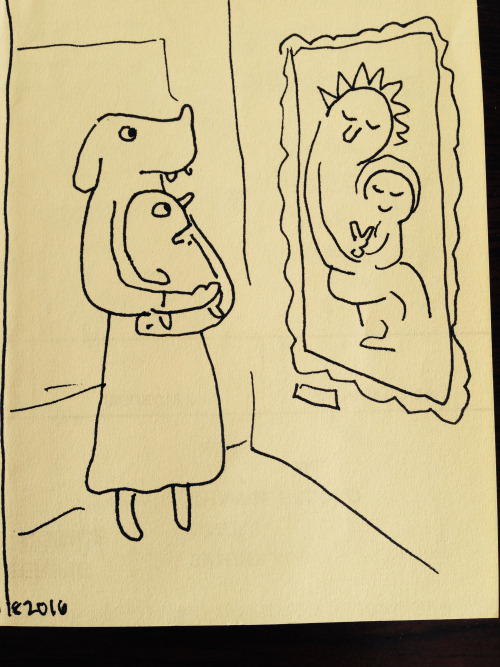

Despite the small, narrative doodle posted to her Tumblr a couple of weeks back, inspirational teacher and cartoonist Lynda Barry clearly has no shortage of strategies for viewing art in a meaningful way.

She takes a Socratic approach with students and readers eager to forge a deeper personal connection to images.

She traces this tendency back forty years, to when she studied with Marilyn Frasca at Evergreen State College. Could Frasca have anticipated what she wrought when she asked the young Barry, “What is an image?”

For Barry, who claims to have spent over forty years trying to answer the above question, there will almost always be an emotional component. In a 2010 interview with The Paris Review, she addressed the ways in which art, visual and otherwise, can fill certain crucial holes:

In the course of human life we have a million phantom-limb pains—losing a parent when you’re little, being in a war, even something as dumb as having a mean teacher—and seeing it somehow reflected, whether it’s in our own work or listening to a song, is a way to deal with it.

The Greeks knew about it. They called it catharsis, right? And without it we’re fucked. I think this is the thing that keeps our mental health or emotional health in balance, and we’re born with an impulse toward it.

No wonder the snaggle-toothed dog woman on Barry’s Tumblr looks so anxious. She craves that elusive something that never much troubled Helen Hockinson’s museum-going comic matrons.

(Had revelation been on the menu, those ladies would have dutifully paged through the most highly recommended guidebook of the day, confident they’d find it within those pages.)

These days, the internet abounds with pointers on how to get the most from art.

Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts lobbies for a four-point method, well suited to classroom discussion.

The Washington Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning art and architecture critic Philip Kennicott prescribes time and silence.

Another critic, New York magazine’s firebrand, Jerry Saltz, recommends an aggressively tactile approach for those who would look at art like an artist. Get up close. Cop a feel. Try to see how any given piece is made. (He himself is given to contemplating art with his hips thrust forward and head tilted back as far as it will go, in duplication of Jasper Johns’ stance.)

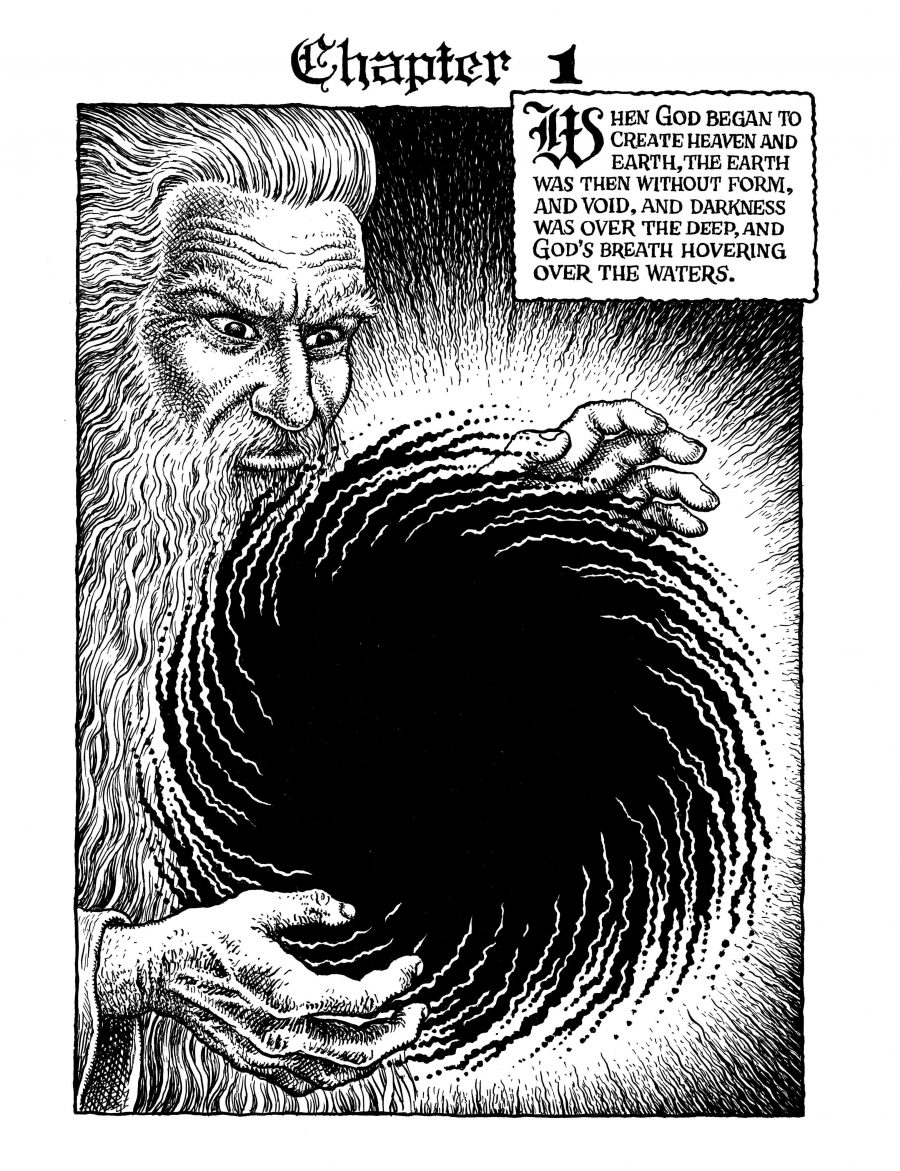

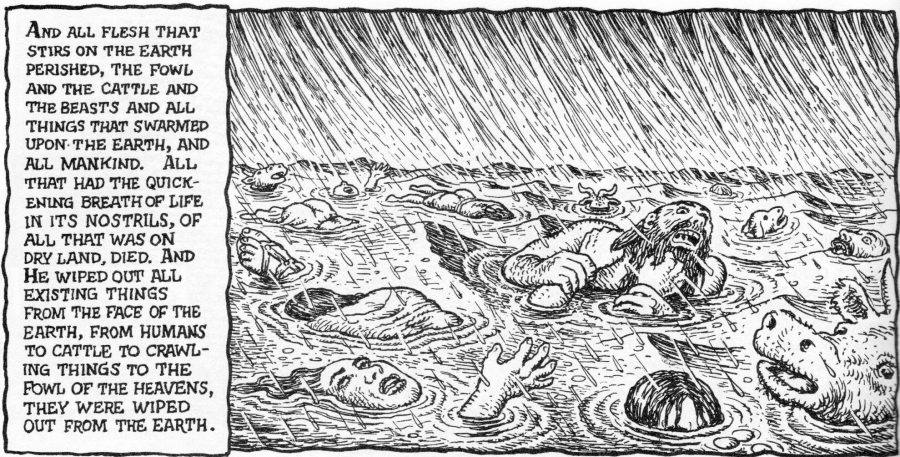

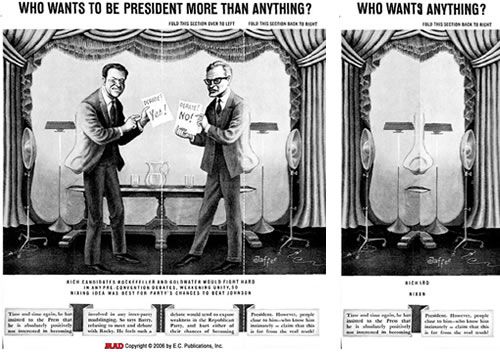

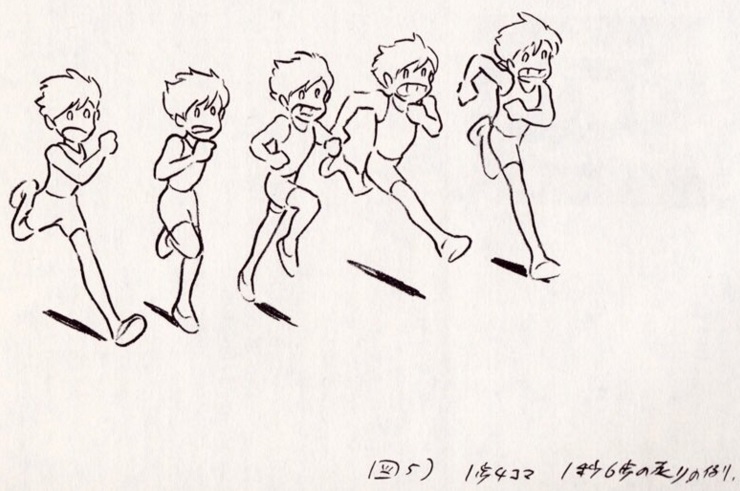

Looking for something more graphic? Abstract Expressionist Ad Reinhardt helped the post-War public get a handle on modern art in his iconic How to Look series.

Former museum educator, Cindy Ingram, the Art Curator for Kids, echoes the spirit of Barry’s sentiment when she states that a child’s interpretation of a work’s meaning is no less valid than Wikipedia’s, the museum’s, or even the artist’s. Adults, don’t squelch a child viewer’s joy of art by telling him or her what to think!

Of course, some of us don’t mind a hint or two to help us feel we’re on the right track. Those in that camp might enjoy the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 82nd and 5th series, in which expert curators wax rhapsodic about their love of particular works in the collection.

You understand that this is just the tip of the proverbial ‘berg…

Readers, if you have any tips for achieving revelation through art, please share them by leaving a comment below.

And don’t forget to lift your shorter companion up so he can see better.

Barry’s short series of images originally appeared on her Tumblr.

Related Content:

Cartoonist Lynda Barry Shows You How to Draw Batman in Her UW-Madison Course, “Making Comics”

Join Cartoonist Lynda Barry for a University-Level Course on Doodling and Neuroscience

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday