Robert Crumb, the iconic, founding figure of the underground and alternative comix scene, began his career as the ultimate outsider. “I was so alienated when I was young that drawing was like my only connection to society,” he says in the video interview above from the Louisiana Channel, “the only thing I could see that was gonna save me from a really dismal fate of god knows what.” He had no social skills and no other abilities to speak of. He was debilitated by self-doubt yet inflated by the buoyant ego of the lone artist determined to “make [his] mark on the world.”

What Crumb calls his “two sides” have never been reconciled, although he has left behind certain racial caricatures in more recent work and he claims, in a recent interview with Nadja Sayej, that he is “no longer a slave to a raging libido.” But his shameless indulgence in exaggerated stereotypes was always a blunt instrument that both pulled readers in and pushed them away from the more subtle satire and pathos in his comics. As an editor at a London gallery put it, “there’s something irreconcilable at the heart of the work that doesn’t resolve towards a single vision of beauty.”

Crumb’s comics are “about seduction and repulsion. You are drawn into the work and you are judging yourself as you look at it.” We are also judging the artist. Crumb has been called racist, misogynist, a bitter, hateful loner with a nihilistic streak five miles wide. These descriptions happen to apply to a significant number of convicted and potential terrorist killers these days, the very people we seek to marginalize from public discourse with hate speech laws and public shaming and shunning.

As you might expect, Crumb has no tolerance for such things as fall under the heading “political correctness.” Suppressing art that offends “can even lead to censorial policies in the government,” he says, defending the rights of the artist to say whatever they deem necessary. His work, he says, even at its most extreme, was necessary. It saved his life. “The artwork I did that used those images and expressed those kinds of feelings, I stand by it…. I still think that’s something that needed to be said and needed to be done…. It probably hurts some people’s feelings to see those images, but still, I had to put it out there.”

Some of Crumb’s imagery is hard to defend, such as his use of blackface imagery from the 1920s and 30s, and his sometimes violent objectification of women, from the point of view of characters nearly impossible to separate from their creator. But why, if his art is confessional, should he not confess? In so doing, he reveals not only his own teeming desires. Crumb illustrated the male hippie unconscious as well as his own.

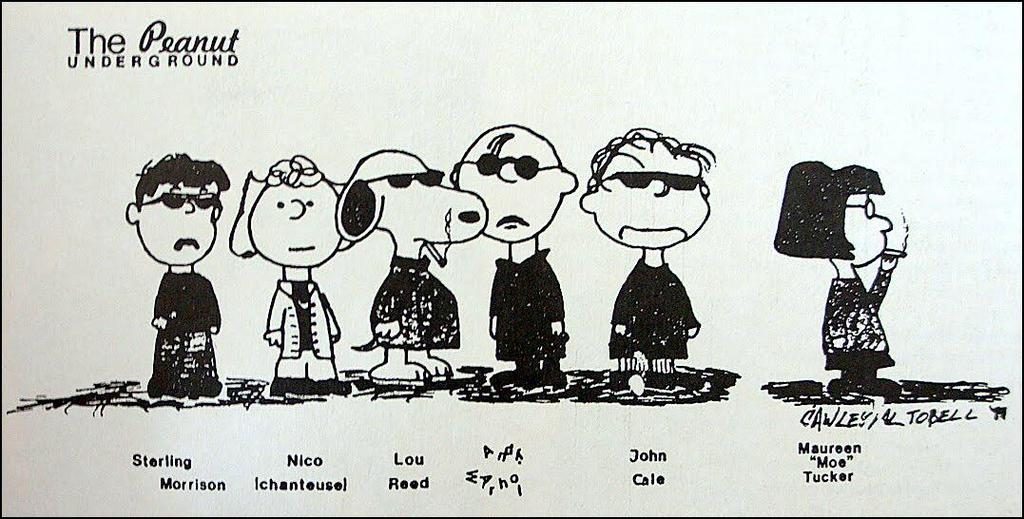

After starting a relative mass movement in underground comix in the 60s (and becoming a reluctant legend for “Keep on Truckin’”), he says, “I decided I don’t want to be America’s best-loved hippie cartoonist. I don’t want that role. So I’ll just be honest about who I am, and the weirdness, and take my chances.” Crumb’s candor happened to lay bare many of the attitudes he observed not only in himself but in the denizens of the San Francisco scene, as he told Jacques Hyzagi in a very revealing Observer interview (which prompted a very bitter feud between the two).

The hippie culture of Haight-Ashbury, where it all started for me, was full of men doing nothing all day and expecting women to bring them food. The ‘chick’ had to provide a home for them, cook meals for them, even pay the rent. It was still very much ingrained from the earlier patriarchal mentality of our fathers, except that our fathers, generally, were providers. Free love meant free sex and food for men. Sure, women enjoyed it, too, and had a lot of sex, but then they served men. Even among left-wing political groups, women were always relegated to secretarial, menial jobs. We were all on LSD, so it took a few years for the smoke to dissipate and for women to realize what a raw deal they were getting with the ne’er-do-well hippie male.

Do we see in Crumb’s work, in which burly, huge-calved women dominate weak-willed men, a celebration or a condemnation of these attitudes? We can say, “it’s complicated,” which sounds like a cop out, or we can go back to the source. Hear Crumb himself explain his work, as a product of two warring selves and a need to draw himself into the world without holding anything back. He showed other artists and writers who were also “born weird,” as he says, that they could tell their stories entirely their own way too.

Related Content:

R. Crumb Illustrates Genesis: A Faithful, Idiosyncratic Illustration of All 50 Chapters

Underground Cartoonist Robert Crumb Creates an Illustrated Introduction to Franz Kafka’s Life and Work

The Confessions of Robert Crumb: A Portrait Scripted by the Underground Comics Legend Himself (1987)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness