Every conversation about education in the U.S. takes place in a minefield. Unless you’re a billionaire who bought the job of Secretary of Education, you’d better be prepared to answer questions about racial and economic equity, disability issues, protections for LGBTQ students, teacher pay and unions, religious charter schools, and many other pressing concerns. These issues are not mutually exclusive, nor are they distinct from questions of curriculum, testing, or achievement. The terrain is littered with possible explosive conflicts between educators, parents, administrators, legislators, activists, and profiteers.

The needs of the most deeply invested stakeholders, as they say, the students themselves, seem to get far too little consideration. What if we in the U.S., all of us, actually wanted to improve the educational experiences and academic outcomes for our children—all of them? Where might we look for a model? Many people have looked to Finland, at least since 2010, when the documentary Waiting for Superman contrasted struggling U.S. public schools with highly successful Finnish equivalents.

The film, a positive spin on the charter school movement, received significant backlash for its cherry-picked examples and blaming of teachers’ unions for America’s failing schools. By contrast, Finland’s schools have been described by William Doyle, an American Fulbright Scholar who studies them, as “the ‘ultimate charter school network’ ” (a phrase, we’ll see, that means little in the Finnish context.) There, Doyle writes at The Hechinger Report, “teachers are not strait-jacketed by bureaucrats, scripts or excessive regulations, but have the freedom to innovate and experiment as teams of trusted professionals.”

Last year, Michael Moore featured many of Finland’s innovative educational experiments in his humorous, hopeful travelogue Where to Invade Next. In the clip above, you can hear from the country’s Minister of Education, Krista Kiuru, who explains to him why Finnish children do not have homework; hear also from a group of high school students, high school principal Pasi Majassari, first grade teacher Anna Hart and many others. Shorter school hours—the “shortest school days and shortest school years in the entire Western world”—leave plenty of time for leisure and recreation. Kids bake, hike, build things, make art, conduct experiments, sing, and generally enjoy themselves.

“There are no mandated standardized tests,” writes LynNell Hancock at Smithsonian, “apart from one exam at the end of students’ senior year in high school… there are no rankings, no comparisons or competition between students, schools or regions.” Yet Finnish students have, in the past several years, consistently ranked in the top ten among millions of students worldwide in science, reading, and math. “If there was one thing I kept hearing over and over again from the Finns,” says Moore above, “it’s that America should get rid of standardized tests,” should stop teaching to those tests, stop designing entire curricula around multiple-choice tests. Hancock describes the results of the Finnish system, and its costs:

Ninety-three percent of Finns graduate from academic or vocational high schools, 17.5 percentage points higher than the United States, and 66 percent go on to higher education, the highest rate in the European Union. Yet Finland spends about 30 percent less per student than the United States.

Moore’s camera registers the shock on Finnish educators’ faces when they hear that many U.S. schools eliminated music, art, poetry and other pursuits in order to focus almost exclusively on testing. Though lighthearted in tone, the segment really drives home the depressing degree to which so many U.S. students receive an impoverished education—one barely worthy of the name—unless they luck into a voucher for a high-end charter school or have the independent means for an expensive private one. In Finland, says the Minister of Education, “all the schools are equal. You never ask where the best school is.”

It’s also illegal in Finland to profit from schooling. Wealthy parents have to ensure that neighborhood schools can give their kids the best education possible, because they are the only option. Many people in the U.S. object to comparisons like Moore’s by noting that societies like Finland are “homogenous” next to what may seem to them like maddening cultural diversity in the U.S. However, Finland has incorporated (not without difficulty) large immigrant and refugee populations—even as its schools continue to improve. The government has responded in part to rising immigration with educational solutions such as this one, a “national initiative to reinforce Finnish higher education institutions (HEIs) as significant stakeholders in migrants’ integration.”

The subtantive differences between the two countries’ educational systems may have less to do with demography and more to do with economics and the training and social status of teachers.

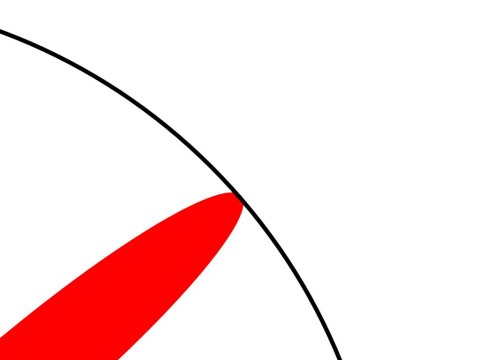

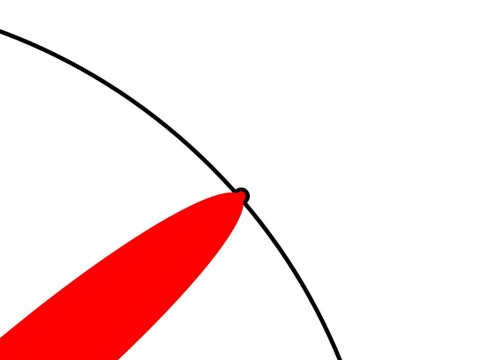

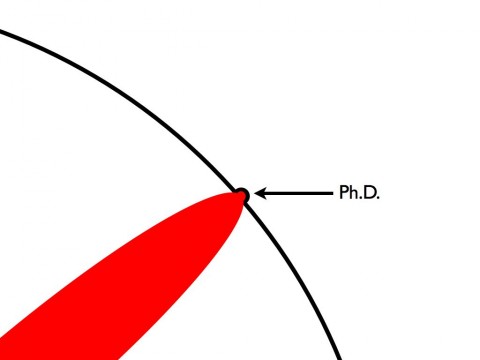

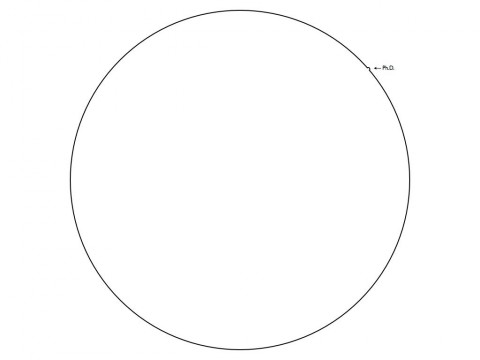

In Finland, writes Doyle, no teacher “is allowed to lead a primary school class without a master’s degree in education, with specialization in research and classroom practice.” Teaching “is the most admired job in Finland next to medical doctors.” And as Dana Goldstein points out at The Nation—a fact Waiting for Superman failed to mention—Finnish teachers are “gasp!—unionized and granted tenure.” Perhaps an even more significant difference the documentary glossed over: in Finland, “families benefit from a cradle-to-grave social welfare system that includes universal daycare, preschool and healthcare, all of which are proven to help children achieve better results at school.”

Hundreds of studies in recent years substantiate this claim. It would seem intuitive that stresses associated with hunger and poverty would have a pernicious effect on learning, especially when poorer schools are so egregiously under-resourced. And the data says as much, to varying degrees. And yet, we are now in the U.S. slashing breakfast and lunch programs that feed hungry children and deciding whether to uninsure millions of families as millions more still lack basic health coverage. Most every American parent knows that quality daycares and preschools can cost as much per year as a decent university education in this country.

It seems to many of us that the atrocious state of the U.S. educational system can only be attributed to an act of will on the part our political elite, who see schools as competition for fundamentalist belief systems, opportunities to punish their opponents out of spite, or as rich fields for private profit. But it needn’t be so. It took 40 years for the Finns to create their current system. In the 1960s, their schools ranked on the very low end—along with those in the U.S. By most accounts, they’ve since shown there can be systems that, while surely imperfect in their own way, work for all kids, embedded within larger systems that prize their teachers and families.

Related Content:

Study Shows That Teaching Young Kids Philosophy Improves Their Academic Performance, Making Them Better at Reading & Math

In Japanese Schools, Lunch Is As Much About Learning As It’s About Eating

Meditation is Replacing Detention in Baltimore’s Public Schools, and the Students Are Thriving

Malcolm Gladwell Asks Hard Questions about Money & Meritocracy in American Higher Education: Stream 3 Episodes of His New Podcast

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness