How does a movie become a “classic”? Explanations, never less than utterly subjective, will vary from cinephile to cinephile, but I would submit that classic-film status, as traditionally understood, requires that all elements of the production work in at least near-perfect harmony: the cinematography, the casting, the editing, the design, the setting, the score. Outside first-year film studies seminars and deliberately contrarian culture columns, the label of classic, once attained, goes practically undisputed. Even those who actively dislike Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, for instance, would surely agree that its every last audiovisual nuance serves its distinctive, bold vision — especially that opening use of “Thus Spake Zarathustra.”

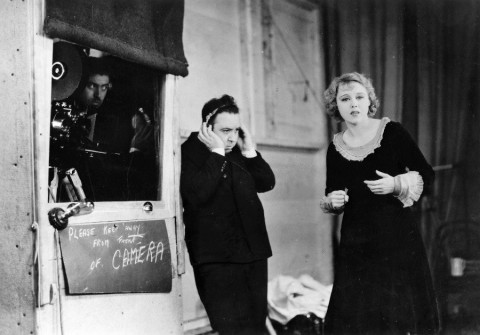

But Kubrick didn’t always intend to use that piece, nor the other orchestral works we’ve come to closely associate with mankind’s ventures into realms beyond Earth and struggles with intelligence of its own invention. According to Jason Kottke, Kubrick had commissioned an original score from A Streetcar Named Desire, Spartacus, Cleopatra, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf composer Alex North.

At the top of the post, you can see 2001’s opening with North’s music, and below you can hear 38 minutes of his score on Spotify. As to the question of why Kubrick stuck instead with the temporary score of Strauss, Ligeti, and Khatchaturian he’d used in editing, Kottke quotes from Michel Ciment’s interview with the filmmaker:

However good our best film composers may be, they are not a Beethoven, a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great orchestral music available from the past and from our own time? [ … ] Although [North] and I went over the picture very carefully, and he listened to these temporary tracks and agreed that they worked fine and would serve as a guide to the musical objectives of each sequence he, nevertheless, wrote and recorded a score which could not have been more alien to the music we had listened to, and much more serious than that, a score which, in my opinion, was completely inadequate for the film.

North didn’t find out about Kubrick’s choice until 2001’s New York City premiere. Not an enviable situation, certainly, but not the worst thing that ever happened to a collaborator who failed to rise to the director’s expectations.

For more Kubrick and classical music, see our recent post: The Classical Music in Stanley Kubrick’s Films: Listen to a Free, 4 Hour Playlist

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & MoreKubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey Gets a Brand New Trailer to Celebrate Its Digital Re-Release

1966 Film Explores the Making of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (and Our High-Tech Future)

James Cameron Revisits the Making of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

Rare 1960s Audio: Stanley Kubrick’s Big Interview with The New Yorker

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.