Between 1908 and 1913, American filmmaker D. W. Griffith made over 400 movies. Over that time, he, along with his fellow Hollywood directors, developed continuity editing. Using such tools as matching eyelines – cutting so that the actors appear to be looking at each other across different shots – and the 180-degree rule – which keeps the actors from switching places on the screen – Griffith and his cohorts created a visual grammar that let audiences forget the film’s artifice and disappear into the story. By the time Griffith released his hugely influential (and hugely racist) masterwork A Birth of A Nation in 1915, the rules of continuity editing had more or less been worked out. This form of storytelling was so successful, and profitable, that it has been used for just about every Hollywood movie that has come out since.

Yet just as these rules were being codified, filmmakers, mostly European, looked for other ways to tell a story. German directors like F. W. Murnau and Robert Wiene experimented with cinematic depictions of the subconscious. French filmmakers like René Clair used camera tricks and odd framing to create works of formal beauty. But it was the filmmakers in the newly formed Soviet Union that really contributed a new way of thinking about film – Soviet Montage. You can watch a video about it above.

When the Bolshevik Revolution washed over the country, the number of films in the USSR dried up. One of the few movies available at VGIK, aka The Moscow Film School, was Griffith’s sprawling Intolerance (watch it online here). Lev Kuleshov, a young teacher there, started to take apart the movie and reorder the images. He discovered that the meaning of a scene was radically changed depending on the order of the shots. This led Kuleshov to try an experiment: he juxtaposed the image of a man with a blank expression with a bowl of soup, a young corpse in a coffin and a pretty girl. You can watch it below.

Invariably, audiences praised the actor for his subtlety of performance. Of course, there was no performance. The connection between the two images was made entirely within the head of the viewer. This realization would forever be commemorated in film schools everywhere as the Kuleshov Effect.

Using the French word for assemble, Kuleshov called this “montage.” At the school, however, there was considerable debate over what montage exactly was. One of Kuleshov’s students, Vsevolod Pudovkin envisioned each shot as a brick, one small part that together with other small parts created a cinematic edifice.

Another student, Sergei Eisenstein, proposed a far more dynamic, and revolutionary, form of montage. Eisenstein saw it “as an idea that arises from the collision of independent shots.” An intellectual well versed in theory, Eisenstein compared montage to Karl Marx’s vision of history where a thesis smashes into its antithesis and together, from that wreckage, forms its synthesis.

Eisenstein’s greatest example of montage, and indeed one of the greatest examples of filmmaking ever, is the Odessa Steps scene from his masterpiece Battleship Potemkin. In it, Czarist soldiers massacre a group of protestors, mostly women and children. You can watch it below.

As you can see, it’s a powerful piece of propaganda. There is no way to come away from this movie and not feel like the Czarists are anything but murderous villains. (Nevermind that the movie is wildly inaccurate, historically speaking.) Shots of a grieving mother juxtaposed with images of bayonet wielding troops result in a surprisingly visceral feeling of injustice.

In his writings, Eisenstein outlined the varying types of montage – five kinds in all. The most important, in his eyes, was intellectual montage – a method of placing images together in a way to evoke intellectual concepts. He was inspired by how Japanese and Chinese can create abstract ideas from concrete pictograms. For example, the Japanese symbol for tree is 木. One character for wall is 囗. Put the two together, 困, and you have the character for trouble, because having a tree in your wall is certainly a huge pain in the ass. You can see an example of intellectual montage in the end of the Odessa steps sequence when a stone lion seemingly rises to his feet.

Eisenstein decided to push this idea to the limit with his follow up, October. The movie is deeply strange to watch now. In one famous sequence, Eisenstein compares White Russian general Alexander Kerensky to a peacock and to a cheap Napoleon figurine. It’s proved to be an interesting intellectual exercise but one that left audiences, both then and now baffled.

And below is another, slightly funnier, certainly more contemporary, example of intellectual montage.

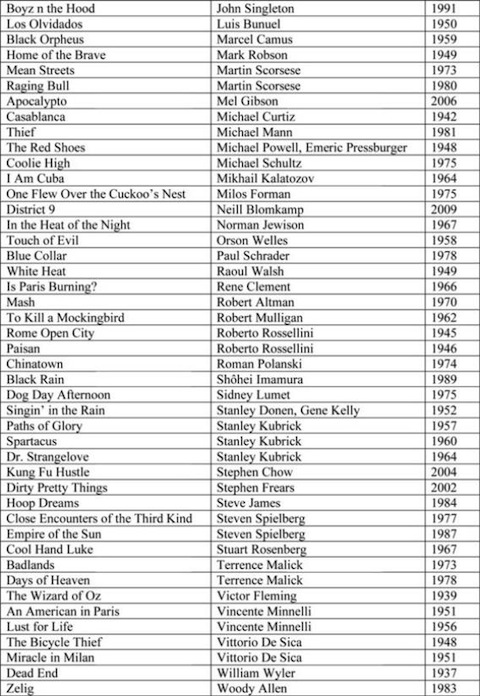

Many of the landmark films mentioned above can be found in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Hitchcock on the Filmmaker’s Essential Tool: The Kuleshov Effect

Watch Battleship Potemkin and Other Free Sergei Eisenstein Films

Jean-Luc Godard’s After-Shave Commercial for Schick

Watch Ten of the Greatest Silent Films of All Time — All Free Online

The Filmmaking of Susan Sontag & Her 50 Favorite Films (1977)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.