Think back to the American independent film boom (sometimes known as “indiewood”) of the nineties. Which of that time’s fresh-faced auteurs strike you as important? Which of their first features retain their impact? Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, certainly; Kevin Smith’s Clerks, which summoned a vast fan culture out of nowhere; Robert Rodriguez’s much-discussed “$7,000 movie” El Mariachi; Steven Soderbergh’s concept-proving Sex, Lies, and Videotape, perhaps the bellwether of the entire movement. But you may underestimate Richard Linklater’s low-key debut Slacker at your peril.

He constructed the 1991 film (available to view on YouTube) as a series of set pieces — some irreverent, some meandering, and some bizarre, but most all of them with stealthily universal resonance — taking place across the college town of Austin, Texas. Douglas Coupland having coined the term “Generation X” with his eponymous novel less than four months before, the North American zeitgeist had come to take serious, if smirking, notice of all these slouchy twentysomethings who seemed to turn up without warning, spouting endless streams of ideas, theories, wisecracks, and elaborate plans, yet drained of anything recognizable as ambition. These slackers, as we now call them without hesitation, make up the dramatis personæ of Slacker. You can see them in their own peculiar type of action by watching the picture free online.

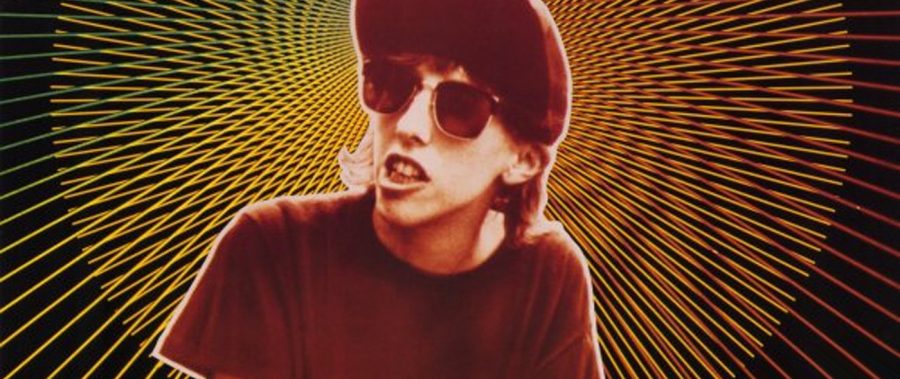

The first slacker to appear, a deeply conflicted motormouth in the back seat of a taxi, comes played by Linklater himself. He seems normal enough, essentially an aimless late-twentysomething you still meet in coffee shops today. But as the camera drifts from block to block, from neighborhood to Austin neighborhood, picking up on any low-momentum story it can, behaviors turn stranger. A bookstore clerk who lives for JFK conspiracy theories logorrheically describes his own book-in-progress on the subject to a helpless acquaintance. A skinny student type living in a room crammed with televisions and even wearing one on back claims desperation to own yet another set. Two fellows egg a third on to throw a typewriter off a bridge and thus symbolically finalize a breakup. And let us never forget the immortal segment wherein Butthole Surfers drummer Teresa Taylor attempts to sell what she describes as a “Madonna pap smear.” Like the early films of Tarantino, Smith, and Rodriguez, Slacker remains thrillingly fun to watch, especially for the enthusiast of micro-budget cinema. But somewhere around its final passage, which begins when a slacker picks up the Pixelvision camera through which we ourselves see the next few minutes, you realize you’ve been watching something on a higher plane. Forced to bet which of the films of this movement scholars will relish enthusiastically a century from now, I’d bet on Slacker, which has now beed added to our ever-expanding list, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

My Best Friend’s Birthday, Quentin Tarantino’s 1987 Debut Film

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.