It can be tempting to view the box office’s domination by visual-effects-laden Hollywood spectacle as a recent phenomenon. And indeed, there have been periods during which that wasn’t the case: the “New Hollywood” that began in the late nineteen sixties, for instance, when the old studio system handed the reins to inventive young guns like Peter Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese. But lest we forget, that movement met its end in the face of competition from late-1970s blockbusters like Jaws and Star Wars, a new kind of blockbuster that signaled a return to the simple thrills of silent cinema.

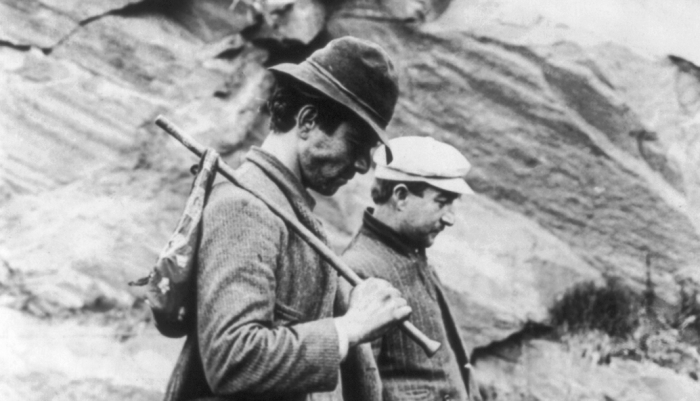

Even a century ago, many moviegoers expected two experiences above all: to be wowed, and to be made to laugh. No wonder that era saw visual comedians like Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin become not just the most famous actors in the world, but some of the most famous human beings in the world.

Staying on top required not just serious performative skill, but also equally serious technical ingenuity, as explained in the new Lost in Time video above. It breaks down just how Lloyd, Keaton, and Chaplin pulled off some of their career-defining stunts on film, putting the actual clips alongside CGI reconstructions of the sets as they would have looked during shooting.

When Lloyd hangs from the arms of a clock high above downtown Los Angeles in Safety Last! (1923), he’s really hanging high above downtown Los Angeles — albeit on a set constructed atop a building, shot from a carefully chosen angle. When the entire façade of a house falls around Keaton in Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), leaving him standing unharmed in a window frame, the façade actually fell around him — in a precisely choreographed manner, but with only a couple of inches of clearance on each side. When a blindfolded Chaplin skates perilously close to a multistory drop in Modern Times (1936), he’s perfectly safe, the edge of the floor being nothing more than a matte painting: one of those analog technologies of movie magic whose obsolescence is still bemoaned by classic-film enthusiasts, from whom CGI, no matter how expensive, never quite thrills or amuses in the same way.

Related content:

The Art of Creating Special Effects in Silent Movies: Ingenuity Before the Age of CGI

Watch the Only Time Charlie Chaplin & Buster Keaton Performed Together On-Screen (1952)

Charlie Chaplin Does Cocaine and Saves the Day in Modern Times (1936)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.