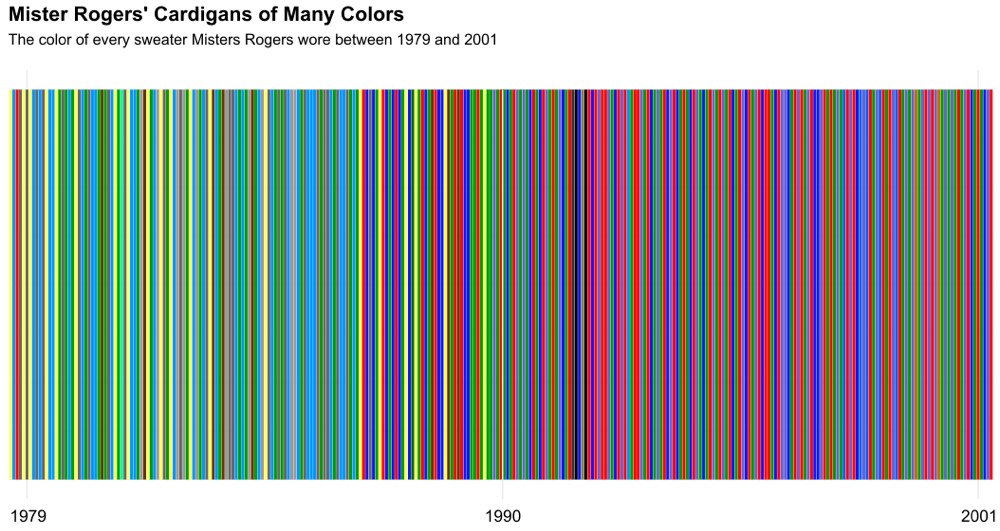

Television host and children’s advocate Fred Rogers was also an ordained Presbyterian minister, for whom spiritual reflection was as natural and necessary a part of daily life as his vegetarianism and morning swims.

His quiet personal practice could take a turn for the public and interactive, as he demonstrated from the podium at the Daytime Emmy Awards in 1997, above.

Accepting a Lifetime Achievement Award, he refrained from running through the standard laundry list of thanks. Instead he invited the audience to join him in spending 10 seconds thinking of the people who “have loved us into being.”

He then turned his attention to his wristwatch as hundreds of glamorously attired talk show hosts and soap stars thought of the teachers, relatives, and other influential adults whose tender care, and perhaps rigorous expectations, helped shape them.

(Play along from home at the 2:15 mark.)

Ten seconds may not seem like much, but consider how often we deploy emojis and “likes” in place of sitting with others’ feelings and our own.

Of all the things Fred Rogers was celebrated for, the time he allotted to making others feel heard and appreciated may be the greatest.

Fifteen years after his death, the Internet ensures that he will continue to inspire us to be kinder, try harder, listen better.

That effect should quadruple when Morgan Neville’s Mister Rogers documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is released next month.

Another sweet Emmy moment comes at the top, when the honoree smooches his wife, Joanne Rogers, before heading off to join presenter Tim Robbins at the podium. Described in Esquire as “hearty and almost whooping in (her) forthrightness,” the stalwart Mrs. Rogers appeared in a handful of episodes, but never played the sort of highly visible role Mrs. Claus inhabited within her husband’s public realm.

The full text of Mister Rogers’ Lifetime Achievement Award award speech is below:

So many people have helped me to come here to this night. Some of you are here, some are far away and some are even in Heaven. All of us have special ones who loved us into being. Would you just take, along with me, 10 seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are, those who cared about you and wanted what was best for you in life. 10 seconds, I’ll watch the time. Whomever you’ve been thinking about, how pleased they must be to know the difference you feel they have made. You know they’re kind of people television does well to offer our world. Special thanks to my family, my friends, and my co-workers in Public Broadcasting and Family Communications, and to this Academy for encouraging me, allowing me, all these years to be your neighbor. May God be with you. Thank you very much.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC this Wednesday, May 16, for another monthly installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.