Dave Eggers, author of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, has a new book coming out in early October, The Circle, a novel about “a young woman who goes to work at an omnipotent technology company and gets sucked into a corporate culture that knows no distinction between work and life, public and private.” Breaking with tradition, The New York Times has placed the novel’s cover on the cover of its own Sunday Magazine. It has also printed a lengthy excerpt from the book. Read it online here, or listen right below (or on iTunes) to a reading of the excerpt by actor Don Graham. It runs 46 minutes.

North Carolina County Celebrates Banned Book Week By Banning Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man … Then Reversing It

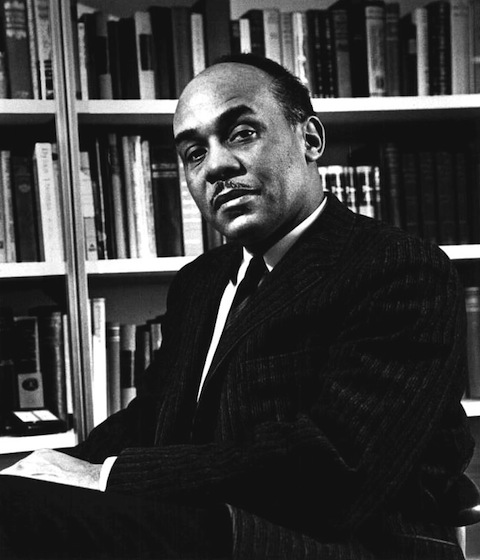

We’re smack in the middle of Banned Books Week, and one particular case of book-banning has received a lot of attention lately, that of Ralph Ellison’s classic 1952 novel Invisible Man, which was censored by the Randolph County, NC school board last week. In response to one parent’s complaint, the board assessed the book, found it a “hard read,” and voted 5–2 to remove it from the high school libraries (prompting the novel’s publisher to give copies away for free to students). One board member stated that he “didn’t find any literary value” in Ellison’s novel, a judgment that may have raised the eyebrows of the National Book Award judges who awarded Ellison the honor in 1953, not to mention the 200 authors and critics who in 1965 voted the novel “the most distinguished single work published in the last twenty years.”

After widespread public outcry, the Randolph County reversed the decision in a special session yesterday. In light of the book’s newfound notoriety after this story, we thought we’d revisit a Paris Review interview Ellison gave in 1954. The interviewers press Ellison on what they see as some of the novel’s weaknesses, but describe Ellison’s masterwork as “crackling, brilliant, sometimes wild, but always controlled.” Below are some highlights from this rich conversation. This interview would not likely sway those shamefully unlettered school board members, but fans of Ellison and those just discovering his work will find much here of merit. Ellison, also an insightful literary critic and essayist, discusses at length his intentions, influences, and theories of literature.

- On his literary influences:

Ellison, who says he “became interested in writing through incessant reading,” cites a number of high modernist writers as direct influences on his work. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land piqued his interest in 1935, and in the midst of the Depression, while he and his brother “hunted and sold game for a living” in Dayton OH, Ellison “practiced writing and studied Joyce, Dostoyevsky, Stein, and Hemingway.” He especially liked Hemingway for the latter’s authenticity.

I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story. I guess many young writers were doing this, but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird. When he describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there.

- On literature as protest

Ellison began Invisible Man in 1945, before the Civil Rights movement got going. He drew much of his sense of the novel as a form of social protest from literary sources, claiming that he recognized “no dichotomy between art and protest.”

Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of nineteenth-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself. If social protest is antithetical to art, what then shall we make of Goya, Dickens, and Twain?

All novels are about certain minorities: the individual is a minority. The universal in the novel—and isn’t that what we’re all clamoring for these days?—is reached only through the depiction of the specific man in a specific circumstance.

- On the role of myth and folklore in literature:

Ellison adapts a tremendous amount of black American folklore in Invisible Man, from folk tales to the blues, to give the novel much of its voice and structure. His use of folk forms springs from his sense that “Negro folklore, evolving within a larger culture which regarded it as inferior, was an especially courageous expression” as well as his reading of ritual in the modernist masters he admired. Of the use of folklore and myth, Ellison says,

The use of ritual is equally a vital part of the creative process. I learned a few things from Eliot, Joyce and Hemingway, but not how to adapt them. When I started writing, I knew that in both “The Waste Land” and Ulysses, ancient myth and ritual were used to give form and significance to the material; but it took me a few years to realize that the myths and rites which we find functioning in our everyday lives could be used in the same way. … People rationalize what they shun or are incapable of dealing with; these superstitions and their rationalizations become ritual as they govern behavior. The rituals become social forms, and it is one of the functions of the artist to recognize them and raise them to the level of art.

- On the moral and social function of literature:

Ellison has quite a lot to say in the interview about what he sees as the moral duty of the novelist to address social problems, which he relates to a nineteenth century tradition (referencing another famously banned book, Huckleberry Finn). Ellison faults the contemporary literature of his day for abandoning this moral dimension, and he makes it clear that his intention is to see the social problems he depicts as great moral questions that American literature should address.

One function of serious literature is to deal with the moral core of a given society. Well, in the United States the Negro and his status have always stood for that moral concern. He symbolizes among other things the human and social possibility of equality. This is the moral question raised in our two great nineteenth-century novels, Moby-Dick and Huckleberry Finn. The very center of Twain’s book revolves finally around the boy’s relations with Nigger Jim and the question of what Huck should do about getting Jim free after the two scoundrels had sold him. There is a magic here worth conjuring, and that reaches to the very nerve of the American consciousness—so why should I abandon it? …Perhaps the discomfort about protest in books by Negro authors comes because since the nineteenth century, American literature has avoided profound moral searching. It was too painful and besides there were specific problems of language and form to which the writers could address themselves. They did wonderful things, but perhaps they left the real problems untouched.

The full Paris Review interview is well worth reading.

Related Content:

Ralph Ellison Reads from His Novel-in-Progress, Juneteenth, in Rare Video Footage (1966)

74 Free Banned Books (for Banned Books Week)

The Paris Review Interviews Now Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

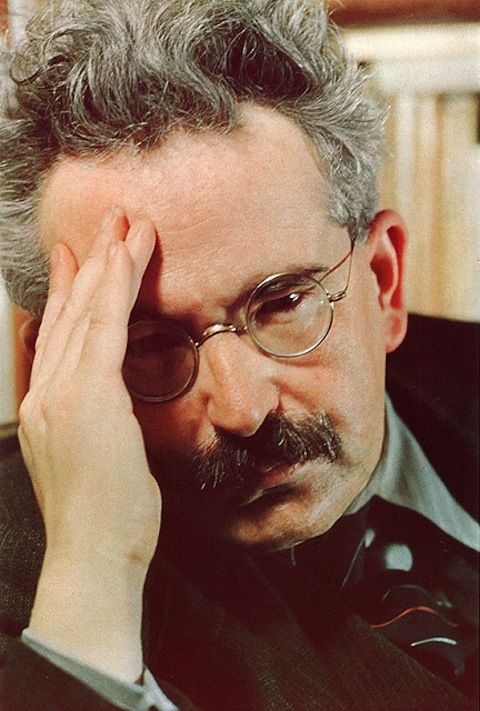

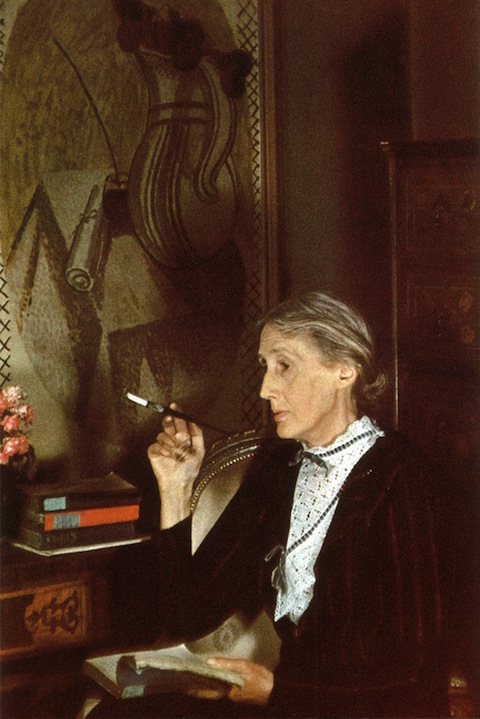

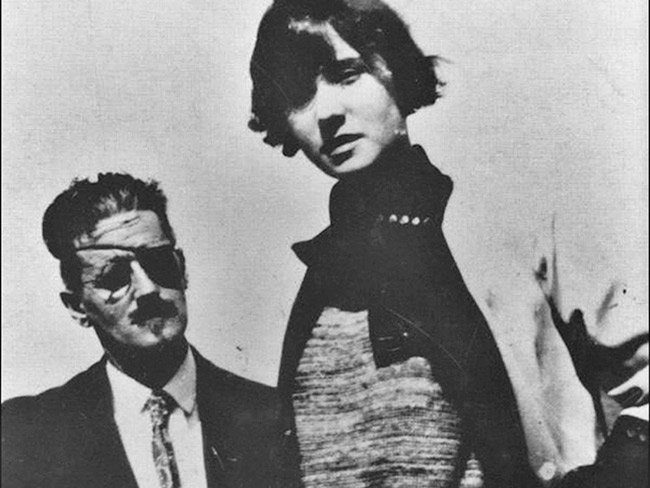

Portraits of Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Walter Benjamin & Other Literary Legends by Gisèle Freund

“Gisèle Freund, the German-born photographer who died in 2000 at 91, is both famous and not famous enough,” writes Katherine Knorr in the New York Times. “She was sometimes chagrined to be best known for some of her portraits,” whose luminary subjects included artists, film stars, and writers. At the top, we have Freund’s 1938 shot of James Joyce with his grandson in Paris. Just below, her photograph of a pensive Walter Benjamin from that same year. At the bottom, her 1939 portrait of a smoking Virginia Woolf. (French novelist, theorist and, Minister for Cultural Affairs André Malraux also sported a cigarette in his 1935 portrait by Freund, an image which made it to a postage stamp in 1996, though with his smoke carefully removed.) Former President Jacques Chirac publicly praised Freund’s ability to “reveal the essence of beings through their expressions.” In Woolf’s case, Freund produced the being in question’s first-ever color portrait.

“[Freund] was an early adapter to color, in 1938, and her first exhibition was in fact a projection of color portraits given in Monnier’s book shop,” Knorr writes. She goes on to describe another exhibition, in 2011, that “similarly projects the portraits within its mock bookshop, turning the show into a guessing game since some of those photographed have enormously famous faces,” while others “are a lot of French intellectuals that most young French people today would not recognize.” While we naturally assume that you, as an Open Culture reader, recognize a fair few more French intellectuals than the average gallery-goer, we can’t help but focus on the fact that so many of the writers of whom Freund’s eye saw the definitive images — not just Joyce, Benjamin, and Woolf, but Beckett, Eliot, Hesse, the list goes on — became the defining writers of their era. Freund herself had just one question: “Explain to me why writers want to be photographed like stars,” she wrote, “and the latter like writers.”

Images by Freund have been collected in the book, Gisèle Freund: Photographs & Memoirs. You can also visit the Freund website to view a collection of portraits.

Related Content:

Philosopher Portraits: Famous Philosophers Painted in the Style of Influential Artists

A‑List Authors, Artists & Thinkers Draw Self Portraits

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

F. Scott Fitzgerald Tells His 11-Year-Old Daughter What to Worry About (and Not Worry About) in Life, 1933

Born 117 years ago today in St. Paul, Minnesota, F. Scott Fitzgerald, that somewhat louche denizen—some might say inventor—of the “Jazz Age,” has been immortalized as the tender young man we see above: Princeton dropout, writer of The Great Gatsby, boozy companion to beautiful Southern belle flapper Zelda Sayre. Amidst all the glamorization of his best and worst qualities, it’s easy to forget that Fitzgerald was also the father of a daughter, Frances Scott Fitzgerald, who went on to have her own successful career as a writer. Unlike the children of some of Fitzgerald’s contemporaries, Frances thrived, which must be some testament to her father’s parenting (and to Zelda’s as well, though she allegedly hoped, like Daisy Buchanan, that her daughter would become a “beautiful little fool”).

We get more than a hint of Fitzgerald’s fatherly character in a wonderful little letter that he sent to her in August of 1933, when Frances was away at summer camp. Fitzgerald, renowned for his extremes, counsels an almost Epicurean middle way—distilling, perhaps, hard lessons learned during his decline in the thirties (which he wrote of candidly in “The Crack Up”). He concludes with a list of things for his daughter to worry and not worry about. It’s a very touching missive that I look forward to sharing with my daughter some day. I’ll have my own advice and silly in-jokes for her, but Fitzgerald provides a very wise literary supplement. Below is the full letter, published in the New York Times in 1958. The typos, we might assume, are all sic, given Fitzgerald’s penchant for such errors:

AUGUST 8, 1933

LA PAIX RODGERS’ FORGE

TOWSON, MATYLAND

DEAR PIE:

I feel very strongly about you doing duty. Would you give me a little more documentation about your reading in French? I am glad you are happy– but I never believe much in happiness. I never believe in misery either. Those are things you see on the stage or the screen or the printed page, they never really happen to you in life.

All I believe in in life is the rewards for virtue (according to your talents) and the punishments for not fulfilling your duties, which are doubly costly. If there is such a volume in the camp library, will you ask Mrs. Tyson to let you look up a sonnet of Shakespeare’s in which the line occurs Lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds…

I think of you, and always pleasantly, but I am going to take the White Cat out and beat his bottom hard, six times for every time you are impertinent. Do you react to that?…

Half-wit, I will conclude. Things to worry about:

Worry about courage

Worry about cleanliness

Worry about efficiency

Worry about horsemanship…

Things not to worry about:

Don’t worry about popular opinion

Don’t worry about dolls

Don’t worry about the past

Don’t worry about the future

Don’t worry about growing up

Don’t worry about anybody getting ahead of you

Don’t worry about triumph

Don’t worry about failure unless it comes through your own fault

Don’t worry about mosquitoes

Don’t worry about flies

Don’t worry about insects in general

Don’t worry about parents

Don’t worry about boys

Don’t worry about disappointments

Don’t worry about pleasures

Don’t worry about satisfactions

Things to think about:

What am I really aiming at?

How good am I really in comparison to my contemporaries in regard to:

(a) Scholarship

(b) Do I really understand about people and am I able to get along with them?

© Am I trying to make my body a useful intrument or am I neglecting it?

With dearest love,

Related Content:

F. Scott Fitzgerald Creates a List of 22 Essential Books, 1936

“Nothing Good Gets Away”: John Steinbeck Offers Love Advice in a Letter to His Son (1958)

Read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Story “May Day,” and Nearly All of His Other Work, Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Recipes of Iconic Authors: Jane Austen, Sylvia Plath, Roald Dahl, the Marquis de Sade & More

It comes as no surprise that Roald Dahl, author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, possessed a sweet tooth. Having dazzled young readers with visions of Cavity-Filling Caramels, Everlasting Gobstoppers, and snozzberry-flavored wallpaper, Dahl’s candy of choice was the more pedestrian Kit-Kat bar. In addition to savoring one daily (a luxury little Charlie Bucket could but dream of, prior to winning that most golden of tickets) he invented a frozen confection called “Kit-Kat Pudding.”

The original recipe is, appropriately, simple enough for a child to make. Stack as many Kit-Kats as you like into a tower, using whipped cream for mortar, then shove the entire thing into the freezer, and leave it there until solid.

Book publicist and self-described literary fangirl Nicole Villeneuve does him one better on Paper and Salt, a food blog devoted to the recipes of iconic authors. Her re-imagined and renamed Frozen Homemade Kit-Kat Cake adds bittersweet chocolate ganache, replacing Dahl’s beloved candy bars with high quality wafer cookies. It remains a pretty straight-forward preparation, not quite as decadent as the Marquis de Sade’s Molten Chocolate Espresso Cake with Pomegranate, but surely more to Dahl’s liking than Jane Austen’s Brown Butter Bread Pudding Tarts would have been. (The author once wrote that he preferred his chocolate straight.)

Villeneuve spices her entry with historical context and anecdotes regarding early 20th-century candy marketing, Dahl’s hatred of the Cadbury Crème Egg, and his dog’s hankering for Smarties. Details such as these make Paper and Salt, which features plenty of savories to go with the sweet, a delicious read even for non-cooks.

Meanwhile, dessert chefs unwilling to source their ingredients from Rite-Aid’s Halloween aisle might try Sylvia Plath’s Lemon Pudding Cakes (“Is it taboo to write about baking and Sylvia Plath?” Villeneuve wonders), C.S. Lewis’ Cinnamon Bourbon Rice Pudding, Willa Cather’s Spiced Plum Kolache or Wallace Stevens’ Coconut Caramel Graham Cookies.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe

Allen Ginsberg’s Personal Recipe for Cold Summer Borscht

How to Make Instant Ramen Compliments of Japanese Animation Director Hayao Miyzaki

Ayun Halliday documented her own sweet tooth in Dirty Sugar Cookies: Culinary Observations, Questionable Taste. Follow her @AyunHallliday

James Joyce’s “Dirty Letters” to His Wife (1909)

Writer and artist Alistair Gentry once proposed a lecture series he called “One Eyed Monster.” Central to the project is what Gentry calls “the cult of James Joyce,” an exemplar of a larger phenomenon: “the vulture-like picking over of the creative and material legacies of dead artists.” “Untalented and noncreative people,” writes Gentry, “are able to build lasting careers from what one might call the Talented Dead.” Gentry’s judgment may seem harsh, but the questions he asks are incisive and should give pause to scholars (and bloggers) who make their livings combing through the personal effects of dead artists, and to everyone who takes a special interest, prurient or otherwise, in such artifacts. Just what is it we hope to find in artists’ personal letters that we can’t find in their public work? I’m not sure I have an answer to that question, especially in reference to James Joyce’s “dirty letters” to his wife and chief muse, Nora.

The letters are by turns scandalous, titillating, romantic, poetic, and often downright funny, and they were written for Nora’s eyes alone in a correspondence initiated by her in November of 1909, while Joyce was in Dublin and she was in Trieste raising their two children in very straitened circumstances. Nora hoped to keep Joyce away from courtesans by feeding his fantasies in writing, and Joyce needed to woo Nora again—she had threatened to leave him for his lack of financial support. In the letters, they remind each other of their first date on June 16, 1904 (subsequently memorialized as “Bloomsday,” the date on which all of Ulysses is set). We learn quite a lot about Joyce’s predilections, much less about Nora’s, whose side of the correspondence seems to have disappeared. Declared lost for some time, Joyce’s first reply letter to Nora in the “dirty letters” sequence was recently discovered and auctioned off by Sotheby’s in 2004.

I do not excerpt here any of the language from Joyce’s subsequent letters, not for modesty’s sake but because there is far too much of it to choose from. If those prudish censors of Ulysses had read this exchange, they might have dropped dead from grave wounds to their sense of decorum. As far as I can ascertain, the letters exist in publication only in the out-of-print Selected Letters of James Joyce, edited by pre-eminent Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann, and in a somewhat truncated form on this site. Alistair Gentry has done us the favor of transcribing the letters as they appear in Ellmann’s Selected Letters on his site here. Of our interest in them, he asks:

Does anyone have the right to read things that were clearly meant only for two specific people…? Now that they have been exposed to the world’s gaze, albeit in a fairly limited fashion, does anybody except these two (who are dead) have any right to make objections about or exercise control over the manner in which these private documents and records of intimacy are used?

Questions worth considering, if not answered easily. Nevertheless, despite his critical misgivings, Gentry writes: “These letters stand on their own as brilliant and, dare I say, arousing Joycean writing. In my opinion they’re definitely worth reading.” I must say I agree. Joyce’s brother Stanislaus once wrote in a diary entry: “Jim is thought to be very frank about himself but his style is such that it might be contended that he confesses in a foreign language—an easier confession than in the vulgar tongue.” In the “dirty letters,” we get to see the great alchemist of ordinary language and experience practically revel in the most vulgar confessions.

Related Content:

James Joyce Plays the Guitar, 1915

On Bloomsday, Hear James Joyce Read From his Epic Ulysses, 1924

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download the Free Audio Book

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

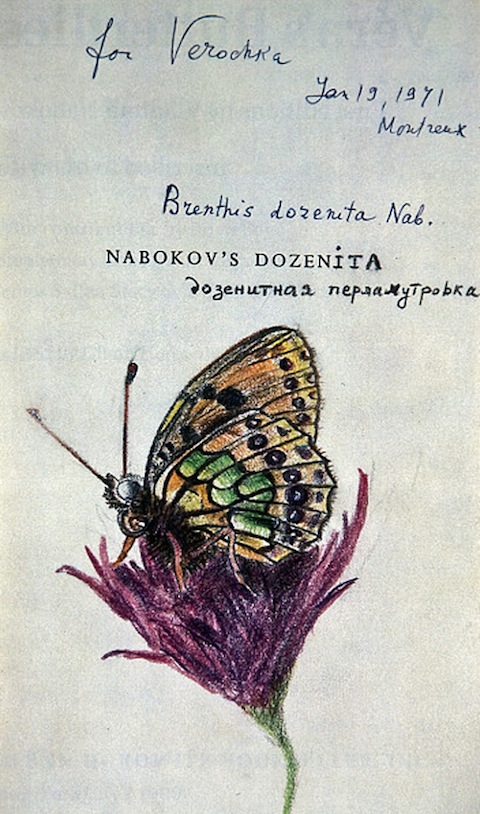

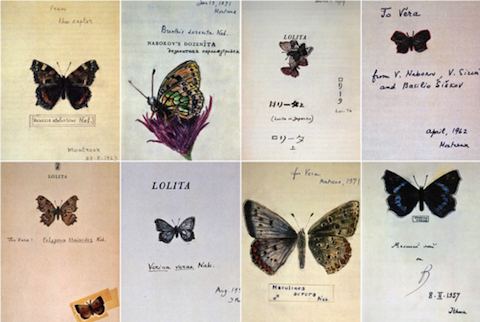

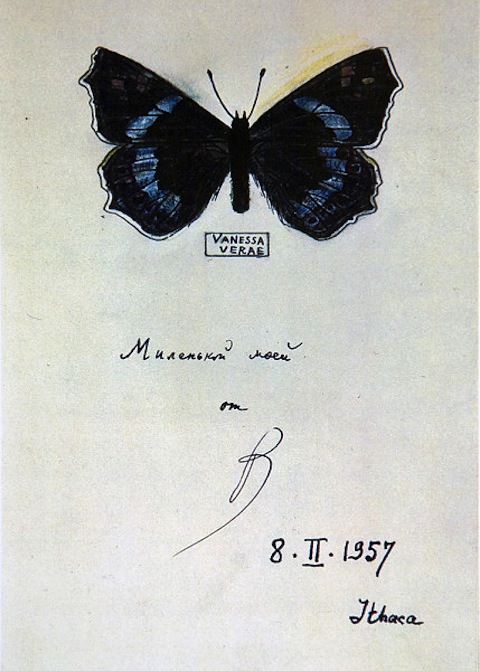

Vladimir Nabokov’s Delightful Butterfly Drawings

We don’t often talk about the hobbies (other than drinking, anyway) of respected twentieth-century writers. But do you know a single Nabokov reader, or even an aspiring Nabokov reader, ignorant of the lepidopterist leanings of the author of Lolita, The Gift, and Pale Fire? The man liked butterflies, as any of the widely seen photographs of him wielding his comically oversized net can attest. But when his eyes turned toward these striking, delicate insects, he didn’t necessarily put down his pen. Nabokov’s wife Vera, according to a Booktryst post on the sale of his book and manuscript collections, “treasured nature, art, and life’s other intangibles more highly than material possessions, and Vladimir knew that for Christmas, birthdays and anniversaries” — in Montreux in 1971, Ithaca in 1957, Los Angeles in 1960, or anywhere at any time in their life together — “Vera appreciated his thoughtful and delicate butterfly drawings much more than some trinket. She delighted in these drawings in a way she never did for the landscapes he used to paint for her in earlier days.” For the woman closest to his heart, Nabokov drew the creatures closest to his heart.

“From the age of seven, everything I felt in connection with a rectangle of framed sunlight was dominated by a single passion. If my first glance of the morning was for the sun, my first thought was for the butterflies it would engender.” This he declares in his autobiography Speak, Memory. “I have hunted butterflies in various climes and disguises: as a pretty boy in knickerbockers and sailor cap; as a lanky cosmopolitan expatriate in flannel bags and beret; as a fat hatless old man in shorts.” Despite the passion with which Nabokov pursued lepidoptery, it seemed, in his lifetime, his accomplishments in the field would remain mostly non-professional; he began one book called Butterflies of Europe and another called Butterflies in Art, but finished neither.

But in 2000, out came the 782-page Nabokov’s Butterflies, which collects, as its co-editor Brian Boyd writes in the Atlantic, “his astonishingly diverse writing about butterflies, whether scientific or artistic, published or unpublished, carefully finished or roughly sketched, in poems, stories, novels, memoirs, scientific papers, lectures, notes, diaries, letters, interviews, dreams.” And in 2011, a hypothesis he had about butterfly evolution had its vindication under the Royal Society of London. But to understand how much butterflies meant to him, we need look no further than the title pages of the volumes he gave his wife.

via Book Tryst

Related Content:

Vladimir Nabokov Creates a Hand-Drawn Map of James Joyce’s Ulysses

Vladimir Nabokov Marvels Over Different Lolita Book Covers

Vladimir Nabokov (Channelled by Christopher Plummer) Teaches Kafka at Cornell

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Edward Said Speaks Candidly about Politics, His Illness, and His Legacy in His Final Interview (2003)

In an excerpt from her memoir published in Salon last month, Najla Said—daughter of literary critic and Palestinian-American political activist Edward Said—recalls her father’s legacy:

To very smart people who study a lot, Edward Said is the “father of postcolonial studies” or, as he told me once when he insisted I was wasting my college education by taking a course on postmodernism and I told him he didn’t even know what it was:

“Know what it is, Najla? I invented it!!!”

I still don’t know if he was joking or serious.

Most likely Said was only half serious, but it’s impossible to overstate the impact of his 1978 book Orientalism on the generations of students and activists that followed. As Najla writes, it’s “the book that everyone reads at some point in college, whether in history, politics, Buddhism, or literature class.” Said’s “postmodernism,” unlike that of Francois Lyotard or many others, avoided the pejorative baggage that came to attach to the term, largely because while he called into doubt certain ossified and pernicious categorical distinctions, he never stopped believing in the positive intellectual enterprise that gave him the tools and the position to make his critiques. He stubbornly called himself a humanist, “despite,” as he writes in the preface to the 2003 edition of his most famous book, “the scornful dismissal of the term by sophisticated post-modern critics”:

It isn’t at all a matter of being optimistic, but rather of continuing to have faith in the ongoing and literally unending process of emancipation and enlightenment that, in my opinion, frames and gives direction to the intellectual vocation.

In that same preface Said also writes of his aging, of the recent death of two mentors, and of “the necessary diminutions in expectations and pedagogic zeal which usually frame the road to seniority.” He does not write about the leukemia that would take his life that same year at the age of 67, ten years ago this month.

For the interview above, however, Said’s last, he speaks candidly about his illness. Fittingly, the video opens with a quote from Roland Barthes: “The only sort of interview that one could, if forced to, defend would be where the author is asked to articulate what he cannot write.” Said tells interviewer Charles Glass that his main preoccupation in the past few months had been his illness, something he thought he had “mastered” but which had forced him to confront the incontrovertible fact of his mortality and sapped him of his will to work.

Said, as always, is articulate and engaging, and the conversation soon turns to his other preoccupations: the situation of the Palestinian people and the politics and personal toll of living “between worlds.” He also expresses his disappointment in friends who had become “mouthpieces of the status quo,” banging the drums for war and Western Imperialism in this, the first year of the war in Iraq. One suspects that he refers to Christopher Hitchens, among others, though he is too discreet to name names. Said has a tremendous amount to say on not only the current events of the time but on his entire career as a writer and thinker. Though he’s given dozens of impassioned interviews over the decades, this may be the most honest and unguarded, as he unburdens himself during his final days of those things, perhaps, he could not bring himself to write.

Thanks to Stephanos for sending this video our way.

Related Content:

Stephen Fry & Friends Pay Tribute to Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Hitchens: No Deathbed Conversion for Me, Thanks, But it was Good of You to Ask

Noam Chomsky Calls Postmodern Critiques of Science Over-Inflated “Polysyllabic Truisms”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness