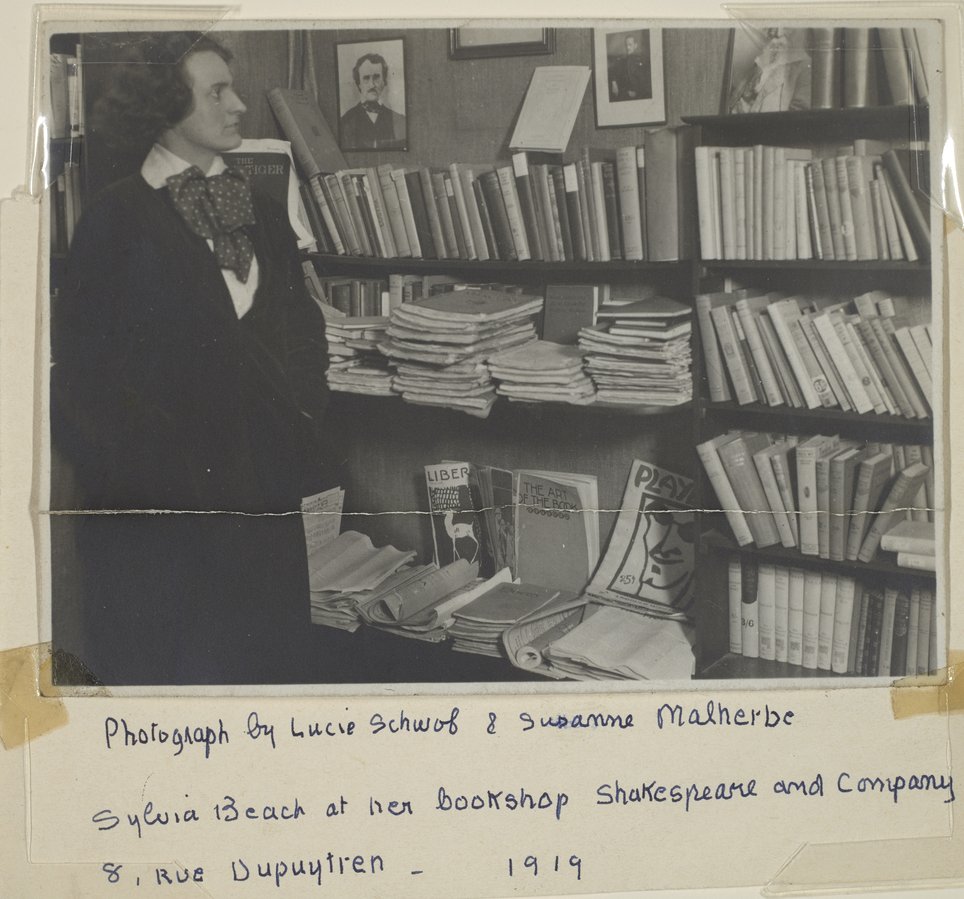

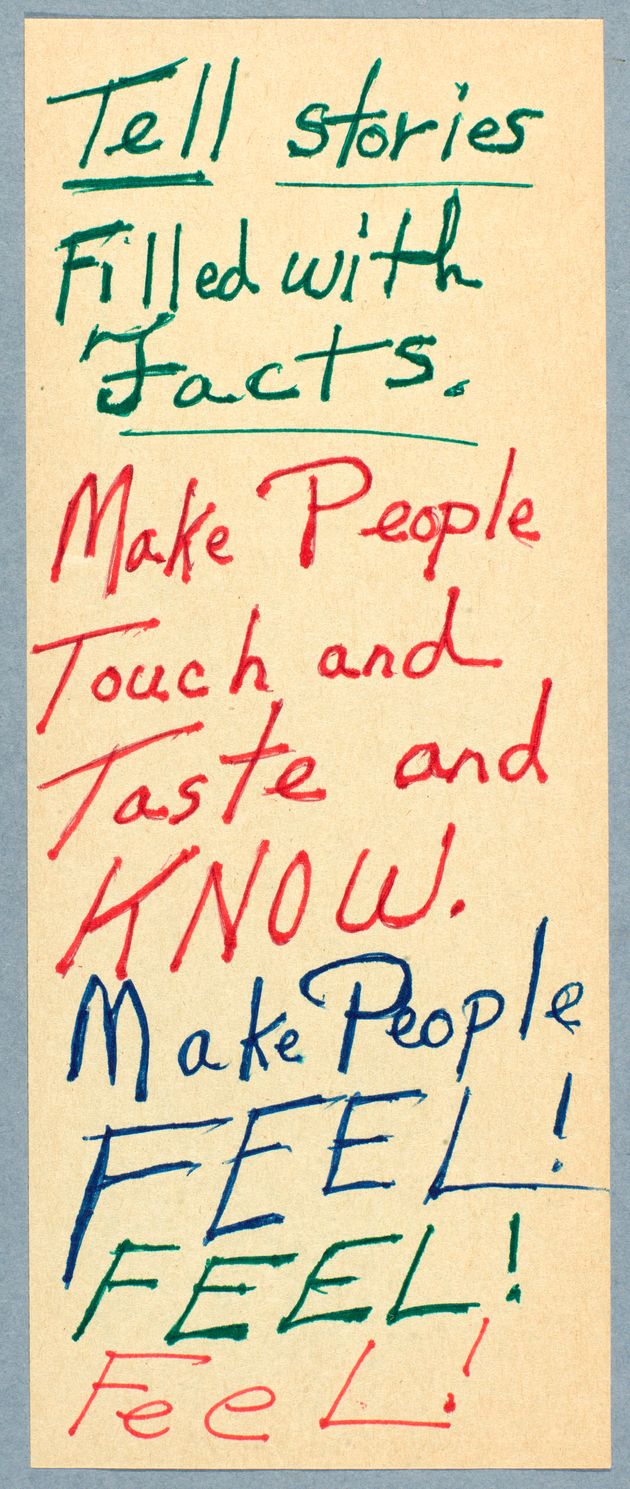

Handwritten notes on the inside cover of one of Octavia E. Butler’s commonplace books, 1988

I was attracted to science fiction because it was so wide open. I was able to do anything and there were no walls to hem you in and there was no human condition that you were stopped from examining. —Octavia E. Butler

Like many authors, the late Octavia E. Butler took up writing at a young age.

At 11, she was churning out tales about horses and romance.

At 12, she saw Devil Girl from Mars, and figured (correctly) she could tell a better story than that, using 2 fingers to peck out stories on the Remington typewriter her mother bought at her request.

At 13, she found a copy of The Writer magazine abandoned on a bus seat, and learned that it was possible to submit her work for publication.

After a decade’s worth of rejection slips, she sold her first two stories, thanks in part to her association with the Clarion Science Fiction Writing Workshop, which she became involved with on the recommendation of her mentor, science fiction writer Harlan Ellison.

She went on to become the first science fiction writer to receive a prestigious MacArthur “genius” award, garnering multiple Hugo and Nebula awards for her work.

An asteroid is named after her, as is a mountain on Pluto’s moon.

Hailed as the Mother of Afro Futurism, she won the PEN American Center lifetime achievement award in writing.

But professional success never clouded her view of herself as the 10-year-old writer who was unsure if library-loving black kids like her would be allowed inside a bookstore.

Identifying as a writer helped her move beyond her crippling shyness and dyslexia. As she wrote in an autobiographical essay, “Positive Obsession”:

I believed I was ugly and stupid, clumsy, and socially hopeless. I also thought that everyone would notice these faults if I drew attention to myself. I wanted to disappear. Instead, I grew to be six feet tall. Boys in particular seemed to assume that I had done this growing deliberately and that I should be ridiculed for it as often as possible.

I hid out in a big pink notebook—one that would hold a whole ream of paper. I made myself a universe in it. There I could be a magic horse, a Martian, a telepath….There I could be anywhere but here, any time but now, with any people but these.

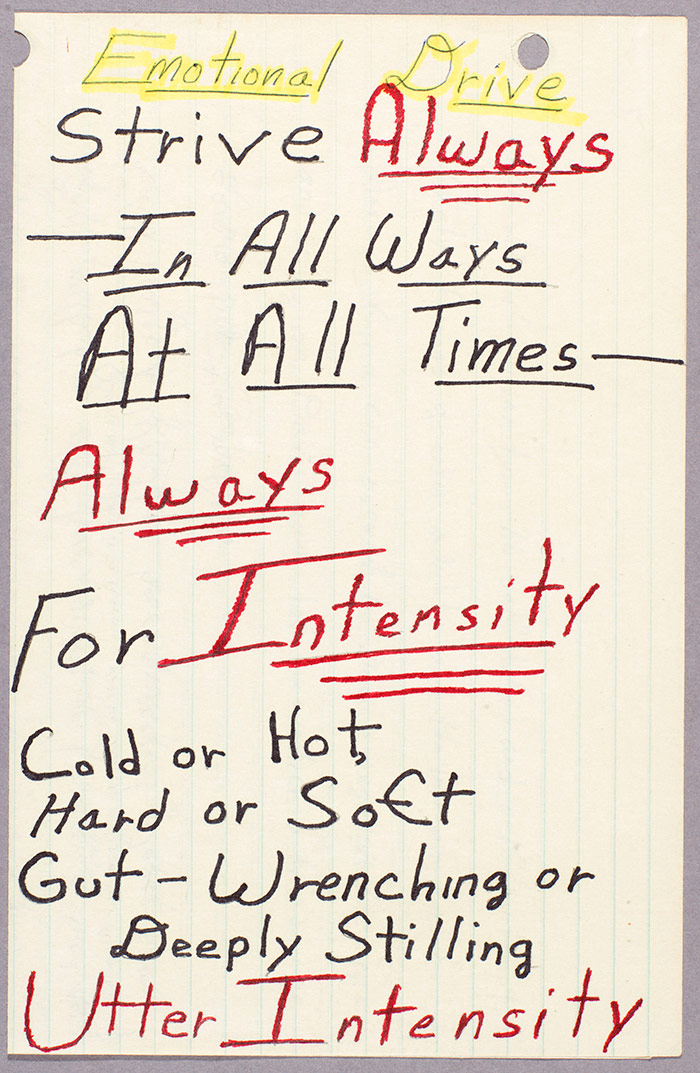

She developed a lifelong habit of cheering herself on with motivational notes, writing them in her journals, on lined notebook paper, in day planners and on repurposed pages of an old wall calendar.

She held herself accountable by writing out demanding schedules to accompany her lofty, documented goals.

And though she wearied of the constant invitations to serve on literary panels devoted to science fiction writers of color, at which she’d be asked the same questions she’d answered dozens of times before, she was resolute about providing opportunities for young black writers … and readers, who found reflections of themselves in her characters. As she remarked in an interview with The New York Times:

When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn’t in any of this stuff I read. The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway. I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing.

Her brand of science fiction—a label she often tried to duck, identifying herself on her business card simply as “writer”—serves as a lens for considering contemporary issues: sexual violence, gun violence, climate change, gender stereotypes, the problems of late-stage capitalism, the plight of undocumented immigrants, and, not least, racism.

She sidestepped utopian science fiction, believing that imperfect humans are incapable of forming a perfect society. “Nobody is perfect,” she told Vibe:

One of the things I’ve discovered even with teachers using my books is that people tend to look for ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys,’ which always annoys the hell out of me. I’d be bored to death writing that way. But because that’s the only pattern they have, they try to fit my work into it.

Learn more about the life and work of Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006) here.

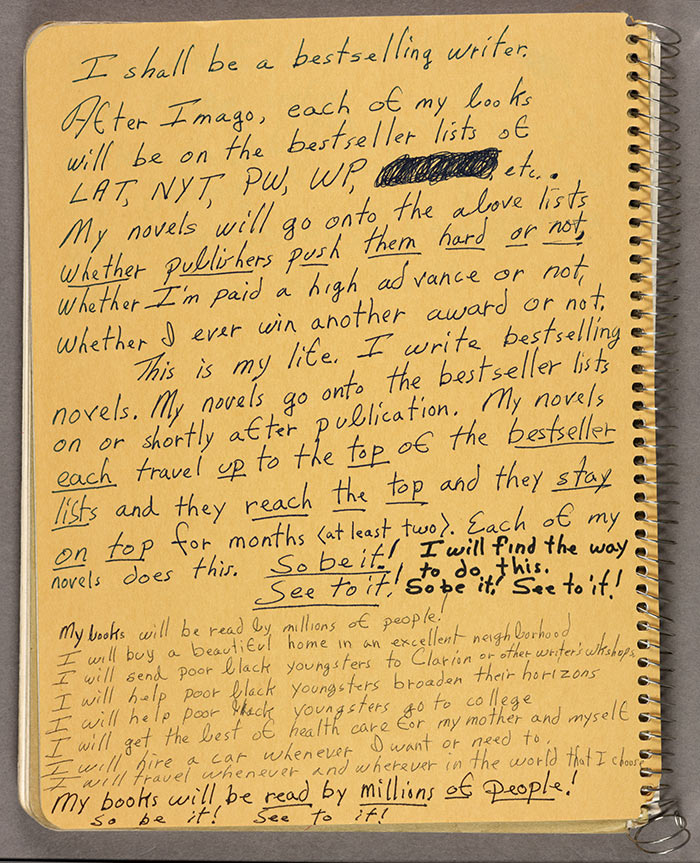

I shall be a bestselling writer. After Imago, each of my books will be on the bestseller lists of LAT, NYT, PW, WP, etc. My novels will go onto the above lists whether publishers push them hard or not, whether I’m paid a high advance or not, whether I ever win another award or not.

This is my life. I write bestselling novels. My novels go onto the bestseller lists on or shortly after publication. My novels each travel up to the top of the bestseller lists and they reach the top and they stay on top for months . Each of my novels does this.

So be it! I will find the way to do this. See to it! So be it! See to it!

My books will be read by millions of people!

I will buy a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood

I will send poor black youngsters to Clarion or other writer’s workshops

I will help poor black youngsters broaden their horizons

I will help poor black youngsters go to college

I will get the best of health care for my mother and myself

I will hire a car whenever I want or need to.

I will travel whenever and wherever in the world that I choose

My books will be read by millions of people!

So be it! See to it!

via Austin Kleon

Related Content:

Why Should We Read Pioneering Sci-Fi Writer Octavia Butler? An Animated Video Makes the Case

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.