The point at which we date the birth of any genre is apt to shift depending on how we define it. When did science fiction begin? Many cite early masters of the form like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells as its progenitors. Others reach back to Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein as the genesis of the form. Some few know The Blazing World, a 1666 work of fiction by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, who called her book a “hermaphroditic text.” According to the judgment of such experts as Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan, sci-fi began even earlier, with a novel called Somnium (“The Dream”), written by none other than German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler. Maria Popova explains at Brain Pickings:

In 1609, Johannes Kepler finished the first work of genuine science fiction — that is, imaginative storytelling in which sensical science is a major plot device. Somnium, or The Dream, is the fictional account of a young astronomer who voyages to the Moon. Rich in both scientific ingenuity and symbolic play, it is at once a masterwork of the literary imagination and an invaluable scientific document, all the more impressive for the fact that it was written before Galileo pointed the first spyglass at the sky and before Kepler himself had ever looked through a telescope.

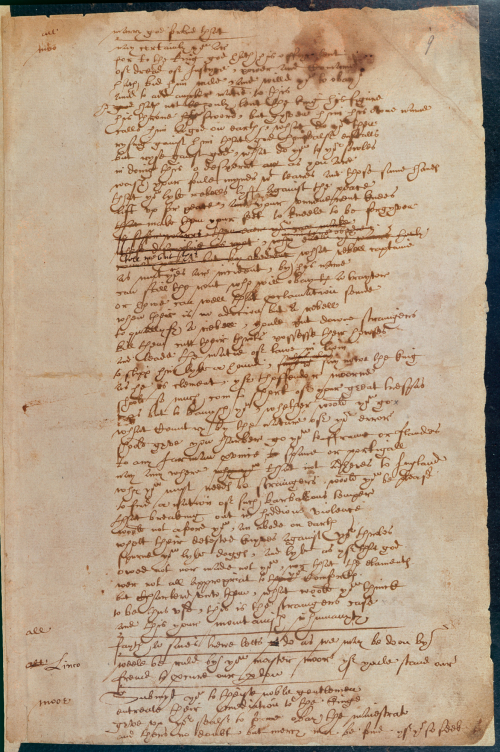

The work was not published until 1634, four years after Kepler’s death, by his son Ludwig, though “it had been Kepler’s intent to personally supervise the publication of his manuscript,” writes Gale E. Christianson. His final, posthumous work began as a dissertation in 1593 that addressed the question Copernicus asked years earlier: “How would the phenomena occurring in the heavens appear to an observer stationed on the moon?” Kepler had first come “under the thrall of the heliocentric model,” Popova writes, “as a student at the Lutheran University of Tübingen half a century after Copernicus published his theory.”

Kepler’s thesis was “promptly vetoed” by his professors, but he continued to work on the ideas, and corresponded with Galileo 30 years before the Italian astronomer defended his own heliocentric theory. “Sixteen years later and far from Tübingen, he completed an expanded version,” says Andrew Boyd in the introduction to a radio program about the book. “Recast in a dreamlike framework, Kepler felt free to probe ideas about the moon that he otherwise couldn’t.” Not content with cold abstraction, Kepler imagined space travel, of a kind, and peopled his moon with aliens.

And what an imagination! Inhabitants weren’t mere recreations of terrestrial life, but entirely new forms of life adapted to lunar extremes. Large. Tough-skinned. They evoked visions of dinosaurs. Some used boats, implying not just life but intelligent, non-human life. Imagine how shocking that must have been at the time.

Even more shocking to authorities were the means Kepler used in his text to reveal knowledge about the heavens and travel to the moon: beings he called “daemons” (a Latin word for benign nature spirits before Christianity hijacked the term), who communicated first with the hero’s mother, a witch practiced in casting spells.

The similarities between Kepler’s protagonist, Duracotus, and Kepler himself (such as a period of study under Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe) led the church to suspect the book was thinly veiled autobiographical occultism. Rumors circulated, and Kepler’s mother was arrested for witchcraft and subjected to territio verbalis (detailed descriptions of the tortures that awaited her, along with presentations of the various devices). It took Kepler five years to free her and prevent her execution.

Kepler’s story is tragic in many ways, for the losses he suffered throughout his life, including his son and his first wife to smallpox. But his perseverance left behind one of the most fascinating works of early science fiction—published hundreds of years before the genre is supposed to have begun. Despite the fantastical nature of his work, “he really believed,” says Sagan in the short clip from Cosmos above, “that one day human beings would launch celestial ships with sails adapted to the breezes of heaven, filled with explorers who, he said, would not fear the vastness of space.”

Astronomy had little connection with the material world in the early 17th century. “With Kepler came the idea that a physical force moves the planets in their orbits,” as well as an imaginative way to explore scientific ideas no one would be able to verify for decades, or even centuries. Hear Somnium read at the top of the post and learn more about Kepler’s fascinating life and achievements at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

Mary Shelley’s Handwritten Manuscript of Frankenstein: This Is “Ground Zero of Science Fiction,” Says William Gibson

Stream 47 Hours of Classic Sci-Fi Novels & Stories: Asimov, Wells, Orwell, Verne, Lovecraft & More

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Free Science Fiction Classics Available on the Web (Updated)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness