Every Poem in Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du Mal” Set to Music, Illustrated and Performed Live

Charles Baudelaire must be a joyful corpse indeed. His work has succeeded as few others’ have, to be so passionately alive 150 years after his death.

Theater Oobleck, a Chicago artistic collective dedicated to creating original affordable theatrical works, has spent the last eleven years assembling Baudelaire in a Box, a cantastoria cycle based on Les Fleurs du Mal.

Why?

Because he would be so irritated. Because he might be charmed

There is a touch of vaudeville and cabaret in Baudelaire. He tended to go big or go home. Home to his mother.

Because he invented the term “modernity” and even now no one quite knows what it means. Because he wrote a poetry of immersion perfectly suited to the transience and Now-ness of song and of the Ever-Moving scroll. Because we never had a proper goth phase. Sex and death! For all these reasons, and for the true one that remains just out of our grasp.

Each new installment features a line-up of musicians performing live adaptations of another 10 to 15 poems, as artist Dave Buchen’s painted illustrations slowly spool past on hand-turned “crankies.”

The resulting “proto music videos” are voluptuously intimate affairs, with plenty of time to reflect upon the original texts’ explicit sexuality, the gorgeous urban decay that so preoccupied one of Romantic poetry’s naughtiest boys.

The instruments and musical palate—klezmer, alt-country, antifolk—are befitting of the interpreters’ well honed downtown sensibilities. The lyrics are drunk on their dark imagery.

The entire project makes for the sort of extravagantly eccentric night out that might lead a young poet to lean close to his blind date, mid-show, to whisper “Wouldn’t it be agreeable to take a bath with me?” No word on whether that line worked for the poéte maudit, who reportedly issued such an invitation to a friend mid-sentence.

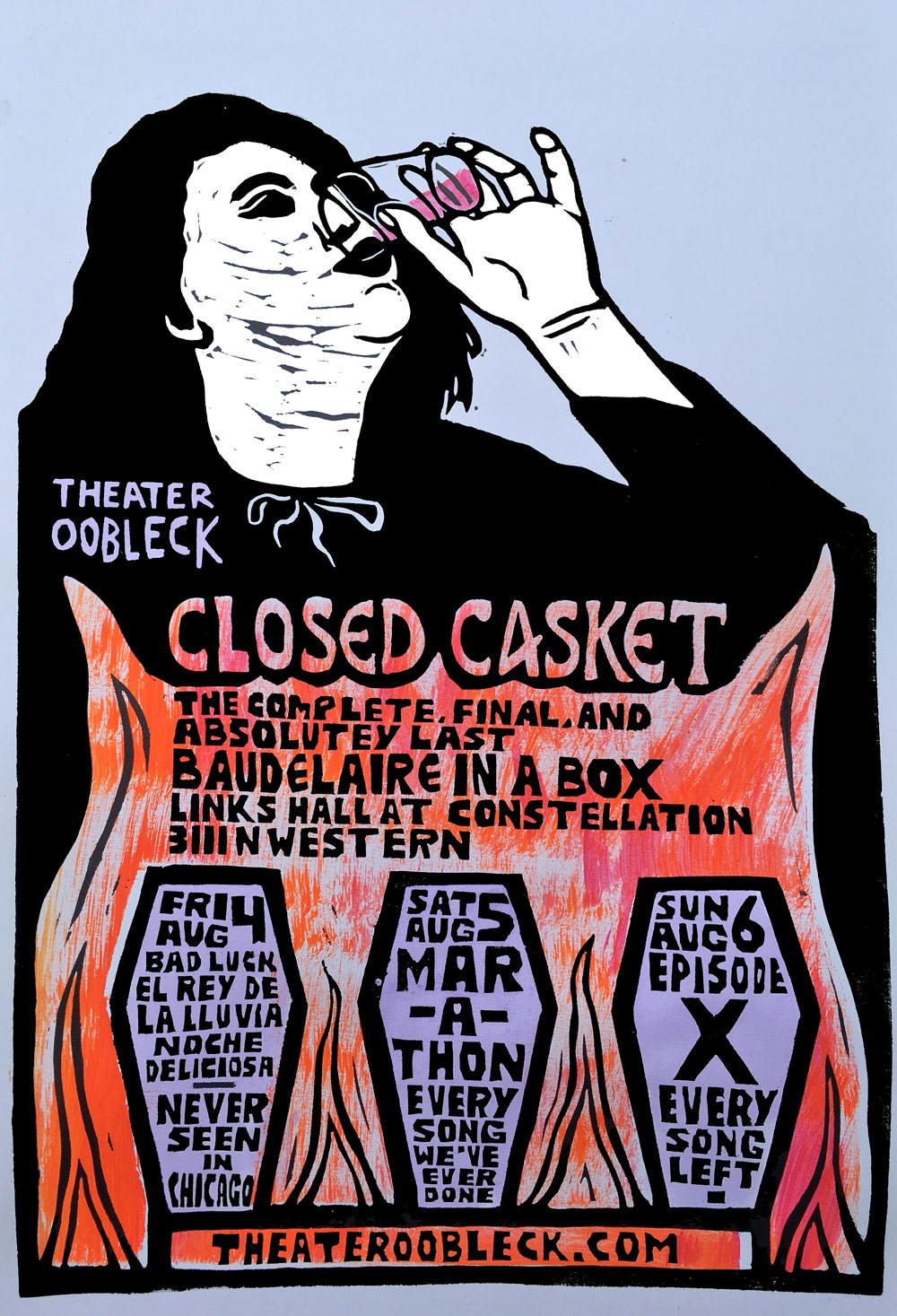

This August, Theater Oobleck intends to observe the sesquicentennial of Baudelaire’s death in grand style with a marathon performance of the complete Baudelaire in a Box, a three-day effort involving 50 artists and over 130 poems.

Allow a few past examples to set the mood:

The Offended Moon From Episode 9 of Baudelaire In A Box, “Unquenched.” Composed and translated by David Costanza. Emmy Bean: vocal, Ronnie Kuller: accordion, T‑Roy Martin trombone, David E. Smith: clarinet, Chris Schoen: vocal, Joey Spilberg: bass.

The Denial of St. Peter Composed, translated and performed by Sad Brad Smith, with Emmy Bean (hand percussion), Ronnie Kuller (accordion), T‑Roy Martin (trombone), Chris Schoen (mandolin), and Joey Spilberg (bass).

The Drag Music composed by Ronnie Kuller, to Mickle Maher’s translation of “L’Avertisseur” by Charles Baudelaire. Performed by: Emmy Bean (vocal, percussion), Angela James (vocal), Ronnie Kuller (piano, percussion), T‑Roy Martin (vocal), Chris Schoen (vocal), David E. Smith (saxophone), and Joey Spilberg (bass).

The Hard(-est) Working Skeleton Music by Amy Warren, Performed by Nora O’Connor, with Addie Horan, Amalea Tshilds, Kate Douglas, James Becker and Ted Day.

The Possessed Written and performed by Jeff Dorchen.

You can listen to and purchase songs from Episodes 7 (the King of Rain) and 9 (Unquenched) on Bandcamp.

Some of the participating musicians have released their own albums featuring tracks of their Baudelaire-based tunes.

Theater Oobleck is raising funds for the upcoming Closed Casket: The Complete, Final, and Absolutely Last Baudelaire in a Box on Kickstarter, with music and prints and originals of Buchen’s work among the premiums at various pledge levels.

All images used with permission of artist Dave Buchen.

Related Content:

Great 19 Century Poems Read in French: Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine & More

Baudelaire, Balzac, Dumas, Delacroix & Hugo Get a Little Baked at Their Hash Club (1844–1849)

Henri Matisse Illustrates Baudelaire’s Censored Poetry Collection, Les Fleurs du Mal

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She will be appearing in a live excerpt from CB Goodman’s How to Kill an Elephant this Friday at Dixon Place in New York City. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Hear a Reading of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake Set to Music: Features 100+ Musicians and Readers from Across the World

In a post last year on an ambitious musical adaptation of Finnegans Wake, I noted that—when most in bafflement over the Irish writer’s final, seemingly uninterpretable, work—I turn to Anthony Burgess, who not only presumed to abridge the book, but wrote more lucid commentary than any other scholarly critic or writerly admirer of Joyce. In his study ReJoyce, Burgess described the novel—or whatever-you-call-it—as a “man-made mountain… as close to a work of nature as any artist ever got—massive, baffling, serving nothing but itself, suggesting a meaning but never quite yielding anything but a fraction of it, and yet (like a tree) desperately simple.”

Joyce did seem to aspire to omniscience and the power of godlike creation, to supplant the “old father, old artificer” he beseeches at the end of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. And if Finnegans Wake is a work of nature, it seems to me that we might approach it like naturalists, looking for its inner laws and mechanisms, performing dissections and mounting it, flayed open, on display boards.

Or we might approach it like poets, painters, field recordists—like artists, in other words. We might leave its innards intact, and instead represent what it does to our minds when we confront its nigh-inscrutable ontology.

This latter approach is the one adopted by Waywords and Meansigns’ latest release, which brings together recordings from over 100 artists from 15 different countries—some semi-famous, most thrillingly obscure. Joyce’s book, explains project director Derek Pyle, is “the kind of thing that demands creative approaches—from jazz and punk musicians to sound artists and modern composers, each person hears and performs the text in a way that’s totally unique and endlessly exciting.” We first commented on the endeavor two years ago, when it released 31 hours of unabridged Joyce interpretation. Last year’s second edition greatly expanded on the singing, reading, and experimental noodling of and around Finnegans Wake.

The third edition continues what has becoming a very fine tradition, and perhaps one of the most appropriate responses to the novel in the 78 years since its publication. This release (streamable above, or on Archive.org) adds to the second edition a belated contribution from iconic bassist and songwriter Mike Watt (of The Minutemen, fIREHOSE, and solo fame) and “actor and ‘JoyceGeek” Adam Harvey. (And a Gumby-starring illustration, above, by punk rock cover artist Raymond Pettibon). The third unabridged collection of interpretative musical readings, further up, offers contributions from:

Mercury Rev veterans Jason Sebastian Russo and Paul Dillon, Joe Cassidy of Butterfly Child, Railroad Earth’s Tim Carbone and Lewis & Clarke’s Lou Rogai, psych-rockers Kinski, vocalist Phil Minton, poet S.A. Griffin, translator Krzysztof Bartnicki, “krautrock” pioneer Jean-Hervé Péron of faUSt, British fringe musician Neil Campbell, Martyn Bates of Eyeless in Gaza, Little Sparta with Sally Timms (Mekons) and Martin Billheimer, composer Seán Mac Erlaine, indietronica pioneer Schneider TM, and many more.

If something on that list doesn’t grab you, you may have stumbled into the wrong party. In any case, you’ll find hundreds other readings, songs, etc. to choose from in the expanding three-volume compilation. Or you can listen to it straight through, from the first edition, to the second, to the third. Like the book, this project celebrates, imitates, reflects, and refracts, Waywords and Meansigns admits entry at any point, and nearly always charms even as it perplexes. The fact that no one can really grasp the slippery nature of Finnegans Wake perhaps makes the book, and its best creative interpretations, all the more genuinely for everyone.

Related Content:

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download as a Free Audio Book & Free eBook

Hear All of Finnegans Wake Read Aloud: A 35 Hour Reading

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Why Should We Read Tolstoy’s War and Peace (and Finish It)? A TED-Ed Animation Makes the Case

War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy’s epic novel of Russia in the Napoleonic wars, has for some time borne the unfortunate, if mildly humorous, cultural role as the ultimate unread doorstop. (At least before David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest or Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle.) The daunting length and complexity of its narrative can seem uniquely forbidding, though it’s equaled or exceeded in bulk by the books of early English novelist Samuel Richardson or later masterworks by the German Robert Musil and French Marcel Proust (not to mention the 8,000 page, 27-volume roman Men of Goodwill by Jules Romains.)

But where it may be necessary in certain circles to have a working knowledge of À la recherche du temps perdu’s “madeleine moment,” one needn’t have read every volume of the painstaking work to get the main flavor for this reference. Tolstoy’s novel, on the other hand, is all of a piece, an operatic text of so many disparate threads that it’s nearly impossible to follow only one of them. And “anyone who tells you that you can skip the ‘War’ parts and only read the ‘Peace’ parts is an idiot,” writes Philip Hensher at The Guardian. (Now he tells me….) Hensher also swears one can read War and Peace “in 10 days maximum.” Very likely, if you approach it without fear or prejudice, and take some vacation time. (But “could you read War and Peace in a week,” Tim Dowling teased in those same pages?)

Tolstoy’s massive psychological portrait of Tsarist Russia in thrall to the French emperor remains a cornerstone of world, and of course, Russian literature. Without it, there may have been no Doctor Zhivago or August 1914. “War and Peace is a long book, sure,” concedes the TED-Ed video above from Brendan Pelsue, “but it’s also a thrilling examination of history, populated with some of the deepest, most realistic characters you’ll find anywhere.” Like most hulking novels of the period, the book was originally serialized in a magazine—the pre-HBO means of disseminating compelling drama—but Tolstoy had not intended for it to grow to such a length or take up five years of his life. One story—that of the Decembrists—led to another. Grand, sweeping views of history emerged from examinations of “the small lives that inhabit those events.”

Pelsue makes a persuasive rhetorical case, but also—for most type‑A, over-employed, or highly distractible readers, at least—inadvertently makes the counterargument. There are no main characters in the book. No Anna Karenina or Ivan Ilyich to follow from start to bitter end. “Instead, readers enter a vast interlocking web of relationships and questions” about the nature of love and war. Maybe you’ve already got one of those—like—in all the time you spend not reading novels. So (snaps fingers), what’s the payoff? The upshot? The “madeline moment”? (No offense to Proust.) Well, no one can—or should attempt to—summarize a complex literary work in such a way that we don’t need to read it for ourselves. Nor, can any interpretation be in any way definitive. To his credit Pelsue doesn’t try for anything of the kind.

Instead, he offers up Tolstoy’s “large, loose baggy monster,” in Henry James’ famously dismissive phrase, not as a novel, nor, as Tolstoy countered, an epic poem or historical chronicle, but as a distinctly Russian form of literature and “the sum total of Tolstoy’s imaginative powers, and nothing less.” A blurb that needs some work? We’re only going to miss the point unless we meet the work itself, whether we read it over 10 days or 10 years. The same can be said for so many epic works that lazy people like… well, all of us at times… complain about. There is absolutely no substitute for reading Moby Dick from start to finish at least twice, I’ve told people with such conviction they’ve rolled their eyes, snorted, and almost kicked me, but I haven’t myself been able to digest all of War and Peace, nor even pretended to. Tolstoy’s greatest work has sadly come to most of us as a book it’s perfectly okay to skim (or watch the movie).

It’s a frustrating work, sometimes boring and disagreeable, didactic and annoying. It has “the worst opening sentence of any major novel,” opines Philip Hensher, and “the very worst closing sentence by a country mile.” And it is also perhaps, “the best novel ever written—the warmest, the roundest, the best story and the most interesting.” Tolstoy not only entertains, but he accomplishes his intention, argues Alain de Botton, of increasing his readers’ “emotional intelligence.” I wouldn’t take anyone’s word for it. We are free to reject Tolstoy, as Tolstoy himself rejected Shakespeare, calling the veneration of the Bard “a great evil.” But we’d have to read him first. There must be some good reasons why people who have actually read War and Peace to the end refuse to let the rest of us forget it.

Related Content:

Watch War and Peace: The Splendid, Epic Film Adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s Grand Novel (1969)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Inspiration from Charles Bukowski: You Might Be Old, Your Life May Be “Crappy,” But You Can Still Make Good Art

Now more than ever, there’s tremendous pressure to make it big while you’re young.

Pity the 31-year-old who fails to make it onto a 30-under-30 list…

The soon-to-graduate high schooler passed over for YouTube stardom…

The great hordes who creep into middle age without so much as a TED Talk to their names…

Social media definitely magnifies the sensation that an unacceptable number of our peers have been granted first-class cabins aboard a ship that’s sailed without us. If we weren’t so demoralized, we’d sue Instagram for creating the impression that everyone else’s #VanLife is leading to book deals and profiles in The New Yorker.

Don’t despair, dear reader. Charles Bukowski is about to make your day from beyond the grave.

In 1993, at the age of 73, the late writer and self-described “spoiled old toad,” took a break from recording the audiobook of Run With the Hunted to reflect upon his “crappy” life.

Some of these thoughts made it into Drew Christie’s animation, above, a reminder that the smoothest road isn’t always necessarily the richest one.

In service of his ill-paying muse, Bukowski logged decades in unglamorous jobs —dishwasher, truckdriver and loader, gas station attendant, stock boy, warehouseman, shipping clerk, parking lot attendant, Red Cross orderly, elevator operator, and most notoriously, postal carrier and clerk. These gigs gave him plenty of material, the sort of real world experience that eludes those upon whom literary fame and fortune smiles early.

(His alcoholic misadventures provided yet more material, earning him such honorifics as the ”poet laureate of L.A. lowlife” and “enfant terrible of the Meat School poets.”)

One might also take comfort in hearing a writer as prodigious as Bukowski revealing that he didn’t hold himself to the sort of daily writing regimen that can be difficult to achieve when one is juggling day jobs, student loans, and/or a family. Also appreciated is the far-from-cursory nod he accords the therapeutic benefits that are available to all those who write, regardless of any public or financial recognition:

Three or four nights out of seven. If I don’t get those in, I don’t act right. I feel sick. I get very depressed. It’s a release. It’s my psychiatrist, letting this shit out. I’m lucky I get paid for it. I’d do it for nothing. In fact, I’d pay to do it. Here, I’ll give you ten thousand a year if you’ll let me write.

Related Content:

4 Hours of Charles Bukowski’s Riotous Readings and Rants

Hear 130 Minutes of Charles Bukowski’s First-Ever Recorded Readings (1968)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Metamorfosis: Franz Kafka’s Best-Known Short Story Gets Adapted Into a Tim Burtonesque Spanish Short Film

In one sense, given their spare settings and allegorical feel, the stories of Franz Kafka could play out anywhere. But in another, one can only with difficulty separate those stories from the late 19th- and early 2oth-century central Europe in which Kafka himself spent his short life. This simultaneous connection to place and placelessness (and also, per David Foster Wallace’s interpretation, playfulness, or at least humor of some kind) has made Kafka’s work appealing material indeed for animators, some of whose work we’ve featured here on Open Culture before.

When filmmakers try their hands at live-action Kafka adaptations, though, they tend to find themselves performing acts of not just artistic but cultural transplantation. Just last year we posted Dominic Allen’s Two Men, an award-winning short film that relocates Kafka’s parable “Passers-by” to a remote section of Western Australia.

Working with a much longer and better-known piece of the Kafka canon, director Fran Estévez’s Metamorfosis brings the tale of Gregor Samsa’s sudden transformation into a large insect to Spain — or into the Spanish language, anyway.

The recipient of quite a few awards itself in South America and Europe (including a festival in Kafka’s own birthplace, the current Czech Republic), Metamorfosis combines Kafka’s still-startling man-turned-bug first-person narration with both stark black-and-white footage and illustrations to create just the right claustrophobic, askew atmosphere. The set design, which at certain moments feels right out of early Tim Burton, underscores the fairy-tale aspect of this grim work of imagination. But then, at the very end, the aesthetic ceiling lifts, widening the viewer’s perspective on not just the movie’s foregoing sixteen minutes but on the nature of The Metamorphosis, Kafka’s original story, itself — though, alas, things still don’t end particularly well for poor old Gregor Samsa.

Metamorfosis will be added to our list, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Hear Benedict Cumberbatch Read Kafka’s The Metamorphosis

Franz Kafka Story Gets Adapted into an Award-Winning Australian Short Film: Watch Two Men

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Robert Pirsig Reveals the Personal Journey That Led Him to Write His Counterculture Classic, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974)

I well remember pulling Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance from my parents’ shelves at age twelve or thirteen, working my way through a few pages, and stopping in true perplexity to ask, “what is this?” The book fit no formal scheme or genre I had ever encountered before. I understood its language, but I did not know how to read it. I still don’t, though I’ve had decades to study some of Pirsig’s references and influences, from Plato to Kant to Dōgen. Is this memoir? Fiction? Philosophy? A meditation on machinery, like Henry Adams’ strange essay “The Dynamo and the Virgin”? Yes.

Pirsig’s countercultural classic, published in 1974 after five years of rejections (121 in total) was “not… a marketing man’s dream,” as the editor at his eventual publisher, William Morrow, wrote to him at the time. Nevertheless, it sold—“50,000 copies in three months,” writes the L.A. Times, “and more than 5 million in the decades since. The dense tome has been translated into at least 27 languages…. Its popularity made Pirsig ‘probably the most widely read philosopher alive,’ one British journalist wrote in 2006.’” Pirsig, who died this past Monday, only wrote one other work, the philosophical novel Lila: An Inquiry into Morals. But he will be remembered as an important, if quixotic, figure in 20th century thought.

Zen ostensibly recounts a motorcycle journey Pirsig took with his son, Chris, and two friends. They are shadowed by another character, Phaedrus, the author’s neurotic alter ego. Pirsig poured all of himself into the book: his unorthodox philosophical and spiritual journey, his struggle with schizophrenia, his close and fretful relationship to his son (who later succumbed to drug addiction and was murdered at age 22, five years after Zen came out). It is a book “filled with unanswered and, perhaps, unanswerable questions.”

The kind of deep ambiguity and uncertainty Zen explores is not easy to write about, unsurprisingly, and in the NPR interview above from 1974, Pirsig describes his struggles as a writer—the distractions and intrusions, the self-doubt and confusion. Pirsig secluded himself for much of the writing of the book, and for much of it worked a day job writing technical manuals, which explains quite a lot about its intricate levels of technical detail.

Pirsig’s descriptions of the hard-won self-discipline (and exhaustion) that the writer’s life requires will ring true for anyone who has tried to write a book. He sums up his motivation succinctly: “this was really a compulsive book. If I didn’t do it, I’d feel worse than if I did do it.” But Pirsig found he couldn’t make any progress as a writer until he gave up trying to be “in quotes, a ‘writer,’” or play the role of one anyway. “It was always a separation of my real self from the act of writing,” he says.

His process sounds like the freewriting of Kerouac’s road novel or the automatic writing of the Surrealists: “I could almost watch my hand moving on the page; there was almost no volition one way or the other, it was just happening.” What he identifies as the “sincerity” of the book’s voice helps steady readers who must trust a very unreliable narrator to guide them through a philosophy of what Pirsig calls “quality”—a metaphysical condition that underlies religions and philosophies East and West. “One can meditate,” he wrote, “on the fact that the old English roots for the Buddha and Quality, God and good, appear to be identical.” Pirsig subjected all human endeavor to the scrutiny of “quality,” including so-called “value free” science, a characterization he found dubious.

In the BBC radio interview above, you can hear Pirsig describe his personal and intellectual journey, which took him through a troubled childhood in Minnesota, a tour in the Korean War, an academic career, and eventually a central role in the “whole attempt to reform America” begun by “beatniks” and “hippies” in San Francisco. (Both words, he wrote, were “cliches and stereotypes… invented for the antitechnologists, the antisystem people.”) Urged by a university colleague to pursue the question “what is quality?,” Pirsig undertook an obsessive investigation. His willingness and courage to follow wherever it led defined the rest of his life as a writer and thinker.

12 Classic Literary Road Trips in One Handy Interactive Map

Philosophy of Religion: A Free Online Course

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A 3,350-Song Playlist of Music from Haruki Murakami’s Personal Record Collection

Music and writing are inseparable in the hippest modern novels, from Kerouac to Nick Hornby to Irvine Welsh. It might even be said many such books would not exist without their internal soundtracks. When it comes to hip, prolific modern novelist Haruki Murakami, we might say the author himself may not exist without his soundtracks, and they are sprawling and extensive. Murakami, who is well known for his intense focus and heroic achievements as a marathon and double-marathon runner, exceeds even this consuming passion with his near-religious devotion to music.

Murakami became a convert to jazz fandom at the age of 15 and until age 30 ran a jazz club. Then he suddenly became a novelist after an epiphany at a baseball game. (Hear Ilana Simons read his version of that story in her short animated film above). His first book’s story unfolded in an environment totally permeated by music and music fan culture. From then on, musical references spilled from his characters’ lips, and swirled around their heads perpetually.

What sets Murakami apart from other music-obsessed novelists is not only the degree of his obsession, but the breadth of his musical knowledge. He is as fluent in classical as he as in jazz and sixties folk and pop, and his range in each genre is considerable. He has so much to say about classical music, in fact, that he once published a book of six conversations between himself and Seiji Ozawa, “one of the world’s leading orchestral conductors.” Murakami’s 2013 Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage—its title a reference to Franz Liszt—contains perhaps his most eloquent statement on the role music plays in his life and work, phrased in universal terms:

Our lives are like a complex musical score. Filled with all sorts of cryptic writing, sixteenth and thirty-second notes and other strange signs. It’s next to impossible to correctly interpret these, and even if you could, and could then transpose them into the correct sounds, there’s no guarantee that people would correctly understand, or appreciate, the meaning therein.

“At times,” writes Scott Meslow at The Week, “reading Murakami’s work can feel like flipping through his legendarily expansive record collection.” While we’ve previously featured playlists drawn from Murakami’s jazz obsession and from the general variety of his discriminating (yet thoroughly Western) musical palate, these have been minuscule by comparison with his personal library of LPs, an “inspirational… wall of 10,000 records,” the majority of which are jazz. Murakami admits he always listens to music when he works, and you can see part of his floor-to-ceiling record library, and huge speaker system, in a photo of his desk on his attractively-designed website. Down below, we bring you one of the next best things to actually sitting in his study, a playlist of 3,350 tracks from Murakami’s personal collection. (If you need Spotify’s free software, download it here.)

Hoagy Carmichael, Lionel Hampton, Herbie Hancock, Gene Krupa, Django Reinhardt, Sergei Prokofiev, Frederic Chopin… it’s quite a mix, and one that may not only remind you of several moments in Murakami’s body of work, but will also give you a sampling of the soundtrack to its author’s imagination as he transcribes the “cryptic writing” we have to “transpose… into the correct sounds” as we try to make sense of it.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness