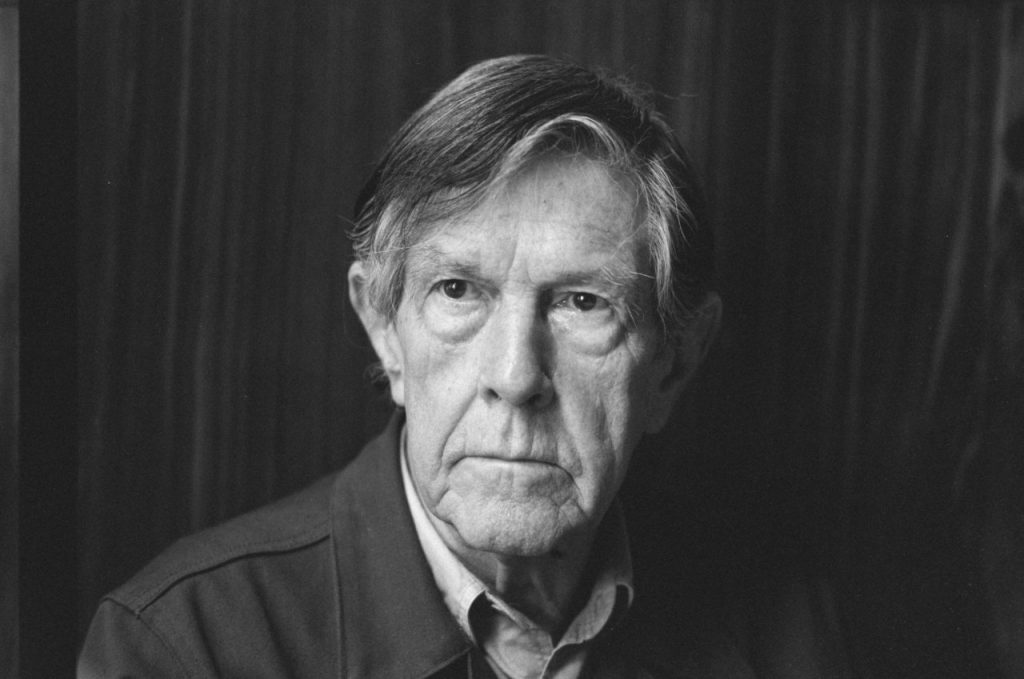

Last summer, a rumor circulated that Cormac McCarthy, one of America’s most beloved living writers, had passed away. In the midst of a devastating year for famous artists and their fans, the announcement appeared on Twitter, but it “was, in fact, a hoax.” As McCarthy’s publisher—recently merged juggernaut Penguin Random House—confirmed, the author of such modern classics as Blood Meridian, All the Pretty Horses, and No Country for Old Men “is alive and well and still doesn’t care about Twitter.” The literary community is better off not only for McCarthy’s good health, but for his disregard of what may be the most fiendishly distracting social media platform of them all. He is still hard at work, on a novel called The Passenger, tentatively slated for release this year.

You can hear excerpts of The Passenger read in the dim, shaky video below, from an event in 2015 at the Santa Fe Institute, an independent scientific think tank where McCarthy keeps an office and where he has plied a secondary trade as a copy-editor for science-themed books, including Quantum Man, physicist Lawrence Krauss’s biography of Richard Feynman. (McCarthy’s “knowledge of physics and maths,” writes Alison Flood at The Guardian, is said to exceed “that of many professionals in the field.”) McCarthy’s latest work seems like a departure for him.

His earlier novels mined the richness of Southern Gothic and Western traditions, and “have subtly woven in science,” writes Babak Dowlatshahi at Newsweek. But The Passenger “will place science in the foreground.” Santa Fe Institute president David Krakauer calls it “full-blown Cormac 3.0—a mathematical [and] analytical novel.”

So we know Cormac McCarthy is a genius, but how is it that he found the time to become a Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellowship-winning novelist and, on the side, a student of theoretical physics and math? His secret involves more than staying off Twitter. As McCarthy tells Oprah Winfrey in the video at the top of the post, excerpted from his first television interview ever in 2007, he has made his work the central focus of his life, to the exclusion of everything else, including money and public adulation from fans and admirers. For example, he answers a question about why he turned down lucrative speaking engagements with, “I was busy. I had other things to do.”

It’s not that I don’t like things, I mean some things are very nice, but they certainly take a distant second place to being able to live your life and being able to do what you want to do. I always knew that I didn’t want to work.

How did he pull off not working? “You have to be dedicated… I thought, ‘you’re just here once, life is brief and to have to spend every day of it doing what somebody else wants you to do is not the way to live it.’” McCarthy doesn’t “have any advice for anybody” about how to avoid the daily grind, except, he says, “if you’re really dedicated, you can probably do it.” As Oprah puts it, “you have worked at not working?” To which he replies, “absolutely, it’s the number one priority.”

Lest we immediately dismiss McCarthy’s philosophy as cluelessness or privilege, we should bear in mind that he willingly endured extreme and “truly, truly bleak” poverty to keep working at not working—or working, rather, on the work he wanted to do. There’s a bit more to becoming a multiple award-winning novelist and MacArthur “Genius” than simply avoiding the 9‑to‑5. But McCarthy suggests that unless artists make their own work their first priority, and material comfort and economic security a “distant second,” they may never truly find out what they’re capable of.

Related Content:

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

The Employment: A Prize-Winning Animation About Why We’re So Disenchanted with Work Today

Cormac McCarthy’s Three Punctuation Rules, and How They All Go Back to James Joyce

Werner Herzog and Cormac McCarthy Talk Science and Culture

Werner Herzog Reads From Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness