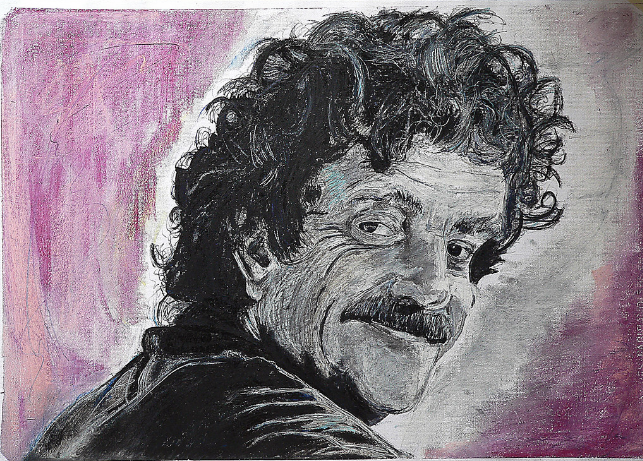

Image by Daniele Prati, via Flickr Commons

The mind of Kurt Vonnegut, like the protagonist of his best-known novel Slaughterhouse-Five, must have got “unstuck in time” somewhere along the line. How else could he have managed to write his distinctive brand of satirical but sincere fiction, hyper-aware of past, present, and future all at once? It must have made him a promising contributor indeed for Volkswagen’s 1988 Time magazine ad campaign, when the company “approached a number of notable thinkers and asked them to write a letter to the future — some words of advice to those living in 2088, to be precise.”

The beloved writer’s letter to the “Ladies & Gentlemen of A.D. 2088” begins as follows:

It has been suggested that you might welcome words of wisdom from the past, and that several of us in the twentieth century should send you some. Do you know this advice from Polonius in Shakespeare’s Hamlet: ‘This above all: to thine own self be true’? Or what about these instructions from St. John the Divine: ‘Fear God, and give glory to Him; for the hour of His judgment has come’? The best advice from my own era for you or for just about anybody anytime, I guess, is a prayer first used by alcoholics who hoped to never take a drink again: ‘God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.’

Our century hasn’t been as free with words of wisdom as some others, I think, because we were the first to get reliable information about the human situation: how many of us there were, how much food we could raise or gather, how fast we were reproducing, what made us sick, what made us die, how much damage we were doing to the air and water and topsoil on which most life forms depended, how violent and heartless nature can be, and on and on. Who could wax wise with so much bad news pouring in?

For me, the most paralyzing news was that Nature was no conservationist. It needed no help from us in taking the planet apart and putting it back together some different way, not necessarily improving it from the viewpoint of living things. It set fire to forests with lightning bolts. It paved vast tracts of arable land with lava, which could no more support life than big-city parking lots. It had in the past sent glaciers down from the North Pole to grind up major portions of Asia, Europe, and North America. Nor was there any reason to think that it wouldn’t do that again someday. At this very moment it is turning African farms to deserts, and can be expected to heave up tidal waves or shower down white-hot boulders from outer space at any time. It has not only exterminated exquisitely evolved species in a twinkling, but drained oceans and drowned continents as well. If people think Nature is their friend, then they sure don’t need an enemy.

You can read the whole thing at Letters of Note, where Vonnegut goes on to give his own interpretation of humanity’s perspective at the time, when “we were seeing ourselves as a new sort of glacier, warm-blooded and clever, unstoppable, about to gobble up everything and then make love — and then double in size again.” He puts the question to his future-inhabiting readers directly: “Is it possible that we aimed rockets with hydrogen bomb warheads at each other, all set to go, in order to take our minds off the deeper problem—how cruelly Nature can be expected to treat us, Nature being Nature, in the by-and-by?”

Finally, Vonnegut issues seven commandments — as much directed to readers of the late 20th century as to readers of the late 21st, or indeed to those of the early 21st in which you read this now — intended to help humanity avert what he sees as the utter catastrophe looming ahead:

- Reduce and stabilize your population.

- Stop poisoning the air, the water, and the topsoil.

- Stop preparing for war and start dealing with your real problems.

- Teach your kids, and yourselves, too, while you’re at it, how to inhabit a small planet without helping to kill it.

- Stop thinking science can fix anything if you give it a trillion dollars.

- Stop thinking your grandchildren will be OK no matter how wasteful or destructive you may be, since they can go to a nice new planet on a spaceship. That is really mean, and stupid.

- And so on. Or else.

Volkswagen had asked him to look one hundred years into the future. As of this writing, 2088 lies less than 75 years ahead, and how many of us would agree that we’ve heeded most or even any of his prescriptions? Then again, Vonnegut grants that pessimism may have got the better of him; perhaps the future will bring with it a utopia after all, one where “nobody will have to leave home to go to work or school, or even stop watching television. Everybody will sit around all day punching the keys of computer terminals connected to everything there is, and sip orange drink through straws like the astronauts,” a comically dystopian utopia, and not an entirely un-prescient one — a Vonnegutian vision indeed.

Related Content:

Hear Kurt Vonnegut Read Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat’s Cradle & Other Novels

22-Year-Old P.O.W. Kurt Vonnegut Writes Home from World War II: “I’ll Be Damned If It Was Worth It”

Kurt Vonnegut Maps Out the Universal Shapes of Our Favorite Stories

Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story

Kurt Vonnegut Explains “How to Write With Style”

Kurt Vonnegut Urges Young People to Make Art and “Make Your Soul Grow”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.