Unless you belong to an older generation, you probably can’t remember the last time the map of the United States underwent any major change. For decades, the boundaries have remained pretty fixed. And yet the map, as we know it, shouldn’t necessarily be considered set in stone.

If billionaire Tim Draper has his way, California voters will decide in 2018 whether California, the home to nearly 40 million people, should be divided into three states called “Northern California,” “Southern California,” and plain “California.” His argument being that California has become too large to govern, and that power should be moved toward smaller, more locally governed entities. Meanwhile, on a parallel track, another group is pushing for California to leave the union altogether. Right there, we have two initiatives that could change the map as we know it.

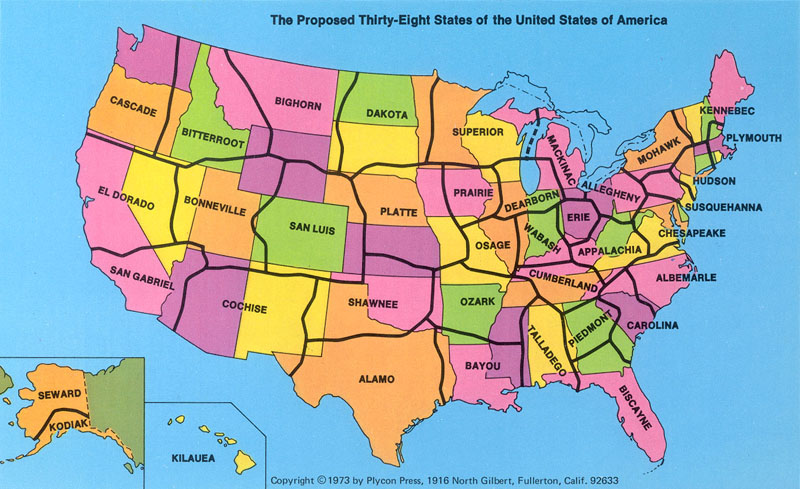

And then there was the time when, back in 1973, George Etzel Pearcy, a California State University geography professor, proposed re-drawing the map of the nation, reducing the number of states to 38, and giving each state a different name. In his creative reworking of things, California would be split into two states–“El Dorado” and “San Gabriel”. Texas would divide into “Alamo” and also “Shawnee” (along with remnants of Oklahoma). And the Dakotas would fuse into one big “Dakota.” In case you’re wondering, Pearcy chose the names by polling geography students.

The logic behind the new map was explained in a 1975 edition of The People’s Almanac.

Why the need for a new map? Pearcy states that many of the early surveys that drew up our boundaries were done while the areas were scarcely populated. Thus, it was convenient to determine boundaries by using the land’s physical features, such as rivers and mountain ranges, or by using a simple system of latitude and longitude.… The practicality of old established State lines is questionable in light of America’s ever-growing cities and the increasing mobility of its citizens. Metropolitan New York, for example, stretches into 2 adjacent States. Other city populations which cross State lines are Washington, D.C., St. Louis, Chicago, and Kansas City. The “straddling” of State lines causes economic and political problems. Who should pay for a rapid transit system in St. Louis? Only those citizens within the boundaries of Missouri, or all residents of St. Louis’s metropolitan area, including those who reach over into the State of Illinois?…

When Pearcy realigned the U.S., he gave high priority to population density, location of cities, lines of transportation, land relief, and size and shape of individual States. Whenever possible lines are located in less populated areas. In the West, the desert, semidesert, or mountainous areas provided an easy method for division. In the East, however, where areas of scarce population are harder to determine, Pearcy drew lines “trying to avoid the thicker clusters of settlement.” Each major city which fell into the “straddling” category is neatly tucked within the boundaries of a new State. Pearcy tried to place a major metropolitan area in the center of each State. St. Louis is in the center of the State of Osage, Chicago is centered in the State of Dearborn. When this method proved impossible, as with coastal Los Angeles, the city is still located so as to be easily accessible from all parts of the State…

According to Rob Lammle, writing in Mental Floss, Pearcy initially got support from “economists, geographers, and even a few politicians.” But the proposal–mainly outlined in a book called A 38 State U.S.A.–eventually withered in Washington, the place where ideas, both good and bad, go to die.

Below you can watch an animation showing how US map has changed in 200 years.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The History of Cartography, the “Most Ambitious Overview of Map Making Ever,” Now Free Online

New York Public Library Puts 20,000 Hi-Res Maps Online & Makes Them Free to Download and Use