Coverage of the refugee crisis peaked in 2015. By the end of the year, note researchers at the University of Bergen, “this was one of the hottest topics, not only for politicians, but for participants in the public debate,” including far-right xenophobes given megaphones. Whatever their intent, Daniel Trilling argues at The Guardian, the explosion of refugee stories had the effect of framing “these newly arrived people as others, people from ‘over there,’ who had little to do with Europe itself and were strangers.”

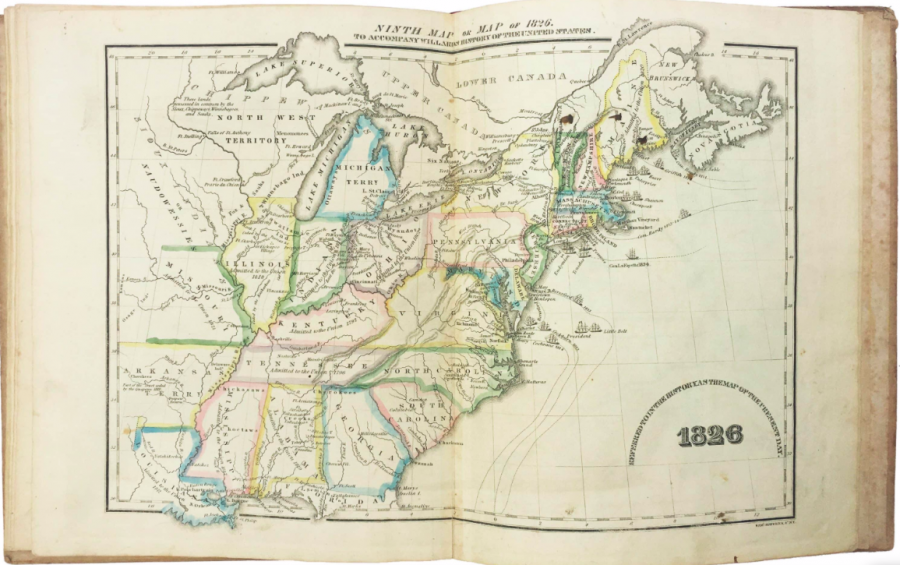

Such a characterization ignores the crucial context of Europe’s presence in nearly every part of the world over the past several centuries. And it frames mass migration as extraordinary, not the norm. The crisis aspect is real, the result of dangerously accelerated movement of capital and climate change. But mass movements of people seeking better conditions, safety, opportunity, etc. may be the oldest and most common feature of human history, as the Science Insider video shows above.

The yellow arrows that fly across the globe in the dramatic animation make it seem like early humans moved by bullet train. But when consequential shifts in climate occurred at a glacial pace—and economies were built on what people carried on their backs—mass migrations happened over the span of thousands of years. Yet they happened continuously throughout last 200,000 to 70,000 years of human history, give or take. We may never know what drove so many of our distant ancestors to spread around the world.

But how can we know what routes they took to get there? “Thanks to the amazing work of anthropologists and paleontologists like those working on National Geographic’s Genographic Project,” Science Insider explains, “we can begin to piece together the story of our ancestors.” The Genographic Project was launched by National Geographic in 2005, “in collaboration with scientists and universities around the world.” Since then, it has collected the genetic data of over 1 million people, “with a goal of revealing patterns of human migration.”

The project assures us it is “anonymous, nonmedical, and nonprofit.” Participants submitted their own DNA with National Geographic’s “Geno” ancestry kits (and may still do so until next month). They can receive a “deep ancestry” report and customized migration map; and they can learn how closely they are related to “historical geniuses,” a category that, for some reason, includes Jesse James.

Do projects like these veer close to recreating the “race science” of previous centuries? Are they valid ways of reconstructing the “human story” of ancestry, as National Geographic puts it? Critics like science journalist Angela Saini are skeptical. “DNA testing cannot tell you that,” she says in an interview on NPR, but it can “make us believe that identity is biological, when identity is cultural.” National Geographic seems to disavow associations between genetics and race, writing, “science defines you by your DNA, society defines you by the color of your skin.” But it does so at the end of a video about a group of people bonding over their similar features.

Despite the significance modern humans have ascribed to variations in phenotype, race is a culturally defined category and not a scientific one. argues Joseph L. Graves, professor of biological sciences at the Joint School of Nanoscience and Nanoengineering.. “Everything we know about our genetics has proven that we are far more alike than we are different. If more people understood that, it would be easier to debunk the myth that people of a certain race are ‘naturally’ one way or another,” or that refugees and asylum seekers are dangerous others instead of just like every other human who has moved around the world over the last 200,000 years.

Related Content:

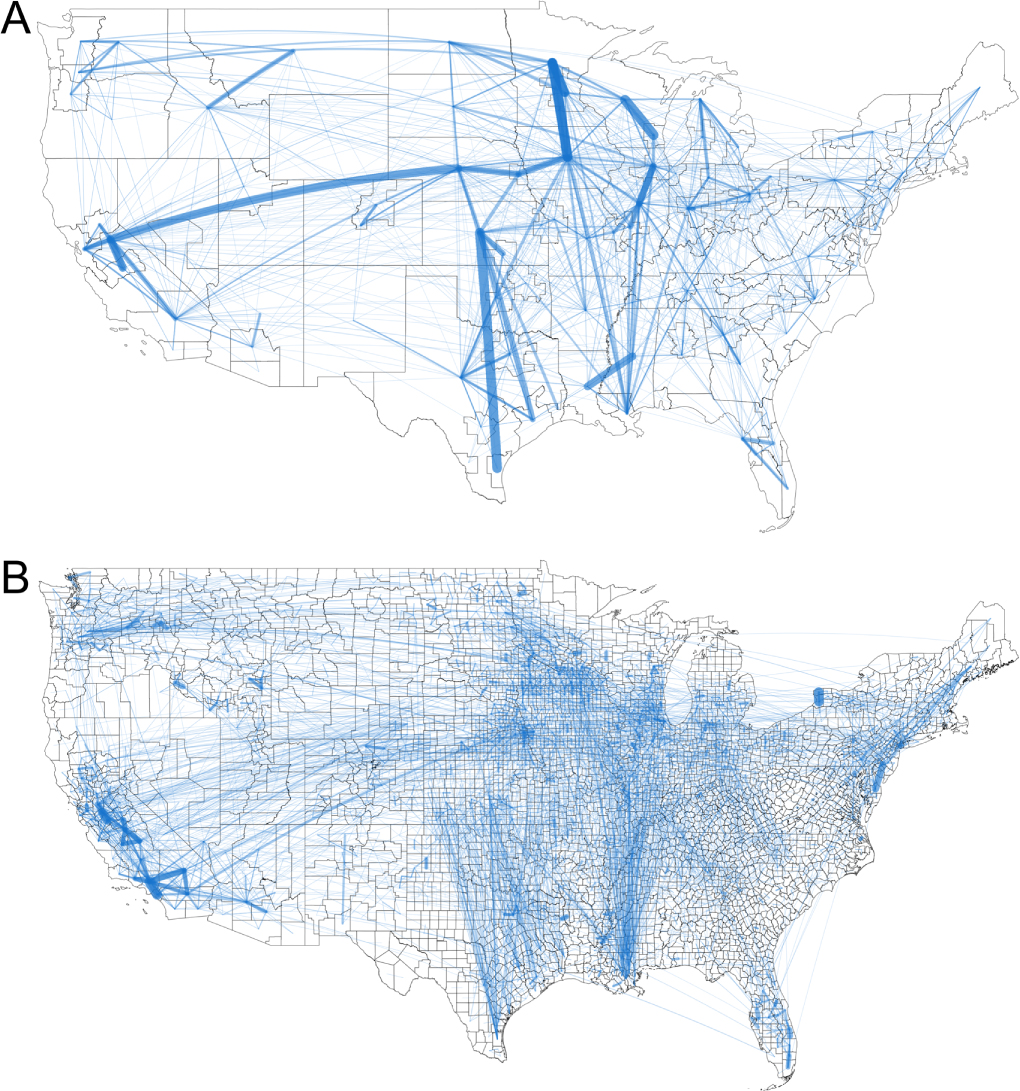

Colorful Animation Visualizes 200 Years of Immigration to the U.S. (1820-Present)

Where Did Human Beings Come From? 7 Million Years of Human Evolution Visualized in Six Minutes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness