With some rare exceptions (Sid and Nancy, I’m Not There, maybe Walk the Line and Cadillac Records), biopics usually stumble badly when they try to recreate the personalities and atmospheres of famous musicians. For this reason I am grateful that no studio has yet attempted a narrative of one of my favorite bands, the not-quite-famous MC5. On the other hand, it’s hard to believe there’s no script in development somewhere. If there’s one band whose story—and music—deserves a wider audience, it’s this one. Sadly, guitarist Wayne Kramer has suppressed a very well-reviewed documentary that might do them as much justice as any film can.

Formed in Lincoln Park Michigan in 1964, the “Motor City 5” became synonymous with Detroit’s leftist political scene. They were also some of the most uncompromising garage rockers to emerge from the era, along with proto-punks The Stooges, with whom they often performed.

By the time of the infamous 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago—well-known for the brutal attacks of police against thousands of aggrieved protesters—the MC5 had become heavily influenced by Fred Hampton and Huey Newton. Under their manager John Sinclair, they became prominent representatives of the “White Panthers,” an anti-racist analogue of the Black Panthers formed on a suggestion of Newton’s.

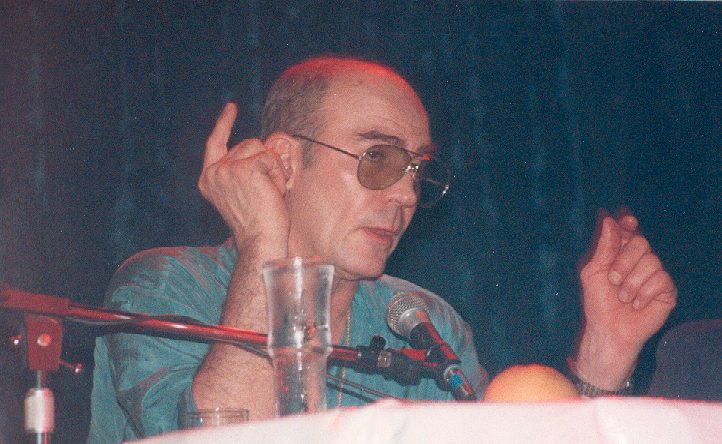

In September of 1968, Sinclair would be indicted for taking part in the bombing a CIA office in Ann Arbor. But exactly one month prior, he presided over the MC5’s appearance at the riotous Chicago Democratic National Convention. The band was booked as part of Abbie Hoffman’s attempt to stage a “Festival of Life,” bringing 100,000 young people to the city “for five days of peace, love, and music,” writes the site Chicago ’68, to “redirect youth culture and music toward political ends.” Fittingly, perhaps, the MC5 was the only band that showed up after Hoffman and his Yippies failed to secure the permits. They played for less than an hour to a crowd of a few thousand. Kramer remembered the day in a 2008 interview:

There was no stage, there was no flatbed truck, there was no sound system, there were no porta-toilets, there was no electricity. We had to run an electrical cord from the hot dog stand to power our gear. We played on the ground in the middle of Lincoln Park in Chicago with the crowd all around us sitting on the ground, in the back standing. I’m going to guess there were maybe 3,000 young people there. And it was very tense. The Chicago police had been very aggressive and very intimidating all day, and even though it was a rock concert and we were the only band to play, it didn’t feel like a rock concert. There was a dark cloud over the day because we knew the likelihood of people being hurt was great.

The only film we seem to have of the event is silent surveillance footage at the top of the post. Further down, see clips of the rioting that ensued, with the band’s hit “Kick Out the Jams” played over it. And just below, see a video of them playing the song over a backdrop of riot footage. They released their debut album, Kick Out the Jams , the following year. It was an uneven collection of performances, but “when they got it right,” says Michael Hann, “they simply got it completely right.” It was certainly their philosophy to go all in. As Kramer described it, “You have to come early, and you have to stay late. The song doesn’t say, ‘Slide out the jams.” It doesn’t say, ‘Stroll out the jams.” It says, ‘Kick out the jams!’”

What I find fascinating about the emergence of the MC5 at this time in history is how great of a contrast they presented to the weary blues of the Rolling Stones, who became grimly linked in ’69 at Altamont with the cynical end of flower power. Despite their association with the violent spectacle of the DNC riots—another sign of the hippie apocalypse—the MC5 became the soundtrack for people power, and in a way bridged the R&B, garage rock, psychedelia, punk, and metal of the gritty 1970s to come. But addiction, political repression, and censorship killed the band a few years later. Lead singer Rob Tyner died in 1991, and guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, who married Patti Smith, passed away in 1994.

Kramer has carried on, and still tours (and gives lectures). When he revisited the DNC in 2008 for an unofficial performance and anti-war protest, he reflected on the politics of the day. “It will be helpful not to have to battle as hard as we have with the Bush administration,” he told The Huffington Post, “but Barack Obama cannot save us. It’s really a matter of people themselves taking action in their own neighborhoods, at their own jobs, in their own homes, with their own friends, their own co-workers, to move us into the future, a more just world.” The people power the MC5 represented lives on even into this grim era, and the band itself will always live in legend, if not—for good or ill—in cinema.

Related Content:

A Gallery of Visually Arresting Posters from the May 1968 Paris Uprising

New Jim Jarmusch Documentary on Iggy Pop & The Stooges Now Streaming Free on Amazon Prime

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness