Musical mash up artist Grant Woolard has found a perfectly ethical way to sidestep copyright issues. Sample the greatest hits of long dead classical composers.

The pragmatically titled “Classical Music Mashup,” above, weaves 57 melodies by Mozart, Beethoven, Verdi, and 30 other greats into one six minute composition.

Woolard invites listeners to separate out the strands, most of which will sound familiar, even if you are unable to name that tune.

(One sharp-eared listener not only accepted the challenge, but posted a complete listing of all the composers and compositions in chronological order with time stamps. Those who don’t mind SPOILERS can view it at the end of this post.)

Those who crave an even more interactive assignment can download the sheet music (for a small fee), then recruit two more pianists to perform the six-handed piece.

You can also buy an audio track of the composition here.

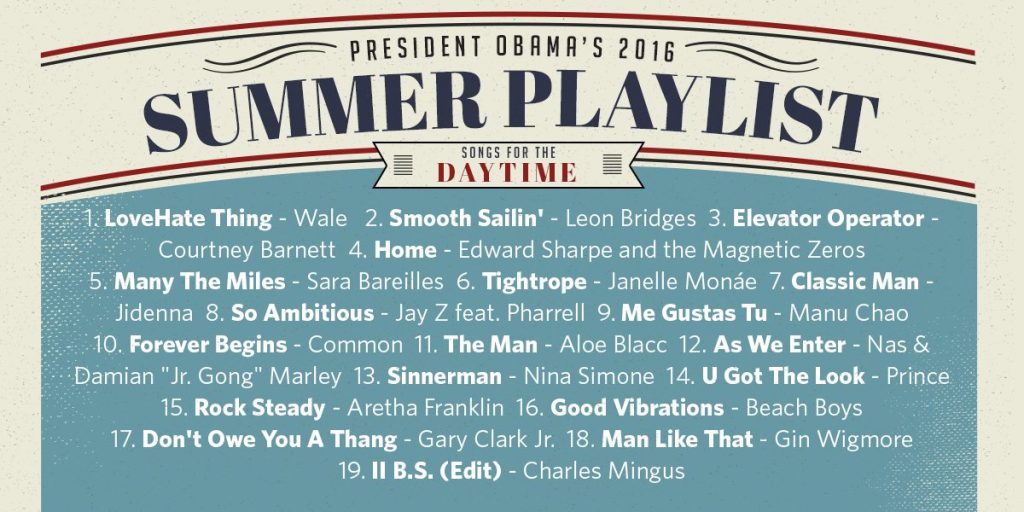

And now, the list of Woolard’s raw ingredients, compliments of youtube commenter, Yifeng Huang:

1. Mozart Eine Kleine Nachtmusik K525 0:01

2. Haydn Symphony 94 “Surprise” II 0:01

3. Beethoven Symphony 9 IV (Ode to Joy) 0:06

4. Mendelssohn Wedding March in Midsummer Night’s Dream, second theme 0:06

5. Dvorak Humoresque No.7 0:13

6. Wagner Lohengerin, Bridal Chorus 0:13

7. Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto 1 0:19

8. Saint-Saens Carnival of Animals: Swan 0:19

9. Bach Well Tempered Clavier Book 1 Prelude 1 0:19

10. Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 0:29

11. Bach Cello Suite No. 1 0:32

12. Mendelssohn Song without Words “Spring” 0:33

13. Schubert Ave Maria 0:40

14. Schubert Symphony 8 “Unfinished” 0:46

15. Verdi “La Donna è Mobile” in Rigoletto 0:51

16. Boccherini String Quartet in E, Op.11 No.5, III. Minuetto 0:55

17. Beethoven für Elise 1:03

18. CPE Bach Solfeggietto 1:04

19. Paganini Capriccio 24 1:11

20. Mozart Piano Sonata No.11 III (Turkish March) 1:15

21. Grieg Piano Concerto 1:22

22. Mozart Requiem Lacrimosa 1:26

23. Schubert Serenade 1:30

24. Chopin Prelude in C minor 1:35

25. Strauss II Overture from Die Fledermaus (Bat) 1:46

26. Brahms 5 Lieder Op.49, IV. Wiegenlied (Lullaby) 1:46

27. Satie Gymnopedie 1:56

28. Debussy Arabesque 2:00

29. Holst Planets, Jupiter 2:05

30. Schubert Trout 2:14

31. Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No.2 2:28

32. Mozart Variation on Twinkle Twinkle Little Star 2:41

33. Schumann Op.68, No.10 Merry Peasant 2:47

34. Schubert Military March in D 2:54

35. Bach* (could be Petzold) Minuet in G 3:00

36. Mozart Piano Sonata No.16 in C, K545 3:07

37. Offenbach Can-can in “Orpheus in the underworld” 3:08

38. Beethoven Piano Sonata No.8 “Pathetique” II 3:18

39. Mozart Die Zauberflöte Overture 3:24

40. Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Overture 3:31

18′. CPE Bach Solfeggietto 3:44

41. Beethoven Symphony 5 “Fate” 3:47

6′. Wagner Wedding March 3:52

42. Rachmaninoff Prelude Op.3 No.2 in C# minor 3:53

18′. CPE Bach Solfeggietto 3:56

43. Chopin Piano Sonata No. 2 III. Funeral March 4:11

44. Williams Imperial March in Star War 4:19

45. Tchaikovsky Marche Slave 4:25

46. Smetana Ma Vlast II. Moldau 4:38

47. Tchaikovsky Nutcracker — Flower Waltz (not the main theme!) 4:45

48. Borodin Polovtsian Dances 4:45

49. Strauss II Blue Danube 4:58

50. Vivaldi Four Seasons I. Spring 5:03

51. Handel Messiah, Hallelujah 5:03

52. Handel The Entrance of the Queen of Sheba 5:08

53. Elgar Pomp and Circumstance Marches No. 1 5:15

54. Pachelbel Canon in D 5:21

55. Mozart Symphony No. 35 in D major (Haffner) K. 385, IV. Finale, Presto 5:27

56. Chopin Etude Op.25 No.9 in G flat, “Butterfly” 5:34

57. Bach Gavotte from French Suite No. 5 in G Major, BWV 816 5:42

Related Content:

The World Concert Hall: Listen To The Best Live Classical Music Concerts for Free

Debussy’s Clair de lune: The Classical Music Visualization with 21 Million Views

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her latest script, Fawnbook, is available in a digital edition from Indie Theater Now. Follow her @AyunHalliday.