It’s always interesting to see how things are made—crayons, Fender Stratocasters, cartoon eggs…

The documentary above takes you through the creation of a cello in the Barcelona workshop of master luthier Xavier Vidal i Roca. (To watch with English subtitles, click the closed caption icon — “CC” — in the lower right corner.)

The opening shots of luthier Eduard Bosque Miñana taking measurements have the jazzy feel of a Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood segment, but once music scholar Ramón Andres gets into the act, things take a turn toward the philosophical.

His thoughts as to the ways the “king of all instruments” speaks to the human condition are commensurate with the level of craftsmanship its construction requires.

(Though seeing Miñana patiently fit a steam-shaped curve to the developing instrument’s c‑bout leads me to question Andres’ choice of anthropomorphizing pronoun. With a waistline like that, surely this cello is a deep-voiced queen.)

The master luthier himself acknowledges that there is always a bit of mystery as to how any given instrument will sound. Most modern cellos are copies of ancient instruments. With the design set, the luthier must channel his or her creative expression into the construction, working with similarly ancient tools — chisels, palette knives, and the like. If power tools come into play, director Laura Vidal keeps them offscreen.

The effect is meditative, hypnotic…I was glad to have the mystery preserved, even as I agree with cellist Lito Iglesias that musicians should make an effort to understand their instruments’ construction, and the reasons behind the selection of particular woods and shapes.

Iglesias also notes that the luthier is the unsung partner in every public performance, the one the audience never thinks to acknowledge.

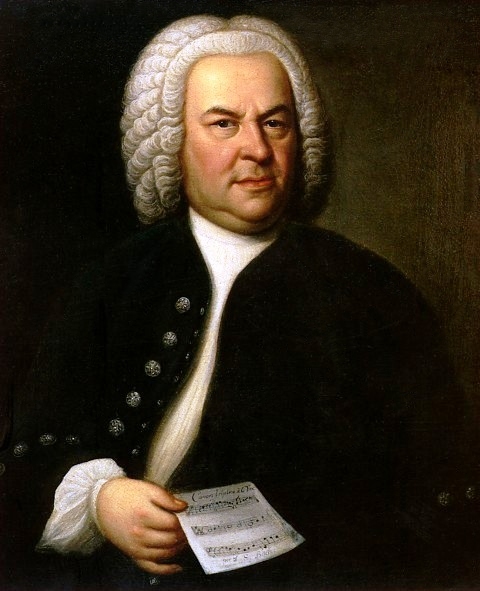

The Sarabande of Bach’s Suite for Solo Cello no. 1 in G major brings things to an appropriately emotional conclusion.

Related Content:

Electric Guitars Made from the Detritus of Detroit

A Song of Our Warming Planet: Cellist Turns 130 Years of Climate Change Data into Music