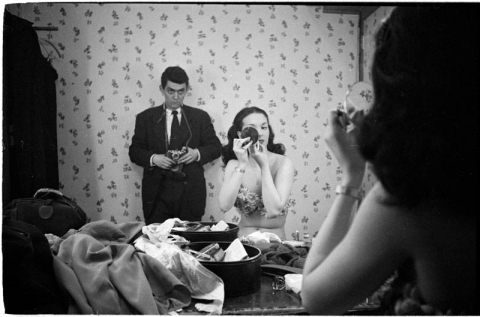

Stanley Kubrick (looking like a creepy Rowan Atkinson above) came of age as a chess-hustling photographer in the jazz-saturated New York City of the 1940s. He began taking pictures at the age of thirteen, when his father bought him a Graflex camera. During his teenage years, Kubrick flirted with a career as a jazz drummer but abandoned the pursuit, instead joining Look Magazine as its youngest staff photographer right out of high school in 1945. His regard for jazz music and culture did not abate, however, as you can see from photographs like Jazz Nights below.

Kubrick worked for Look until 1950 (when he left to begin making films); he captured a wide variety of New York scenes, but often returned to jazz clubs and showgirls, two favorite subjects. I’ve often wondered why Kubrick’s hometown plays so small a role in his films. Unlike also NYC-bred Martin Scorsese, Kubrick seemed eager to get as far away as he could from the city of his youth, but the filmmaker’s love of forties-era jazz never left him. According to longtime assistant, Tony Frewin, “Stanley was a great swing-era jazz fan,” particularly of Benny Goodman.

“He had some reservations about modern jazz. I think if he had to disappear to a desert island, it’d be a lot of swing records he’d take, the music of his childhood: Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Harry James.”

Frewin is quoted in this Atlantic piece about a film Kubrick almost made but didn’t: an exploration of jazz in Europe under the Third Reich. The project began when Kubrick encountered a book in 1985, Swing Under the Nazis, written by another jazz enthusiast, Mike Zwerin, who left music for journalism and spent years collecting stories of jazz preservationists in Germany and formerly occupied Europe. One of those stories—of Nazi officer Dietrich Schulz-Koehn—struck Kubrick as Strangelove-ian and noir-ish. Schulz-Koehn published an illegal underground newsletter reporting back from various jazz scenes in Europe under the pen name, “Dr. Jazz,” the title Kubrick chose for the film project. As Frewin claims:

“Stanley thought there was a kind of noir side to this material…. Perhaps an approach like Dr. Mabuse would have suited the story. Stanley said, ‘If only he were alive, we could have found a role for Peter Lorre.’ ”

Zwerin’s book—and presumably Kubrick’s ideas for a fictionalized take—traced clandestine connections between Nazi Germany, Paris, and the United States, between black and Jewish musicians and Nazi music-lovers. We’ll have to imagine the odd angles and warped perspectives Kubrick would have found in those stories; his fascination with Nazis led him to drop Dr. Jazz for a different project, Aryan Papers, another unmade film with its own intriguing backstory.

Related Content:

Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Stanley Kubrick Never Made

Stanley Kubrick’s Very First Films: Three Short Documentaries

Rare 1960s Audio: Stanley Kubrick’s Big Interview with The New Yorker

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness