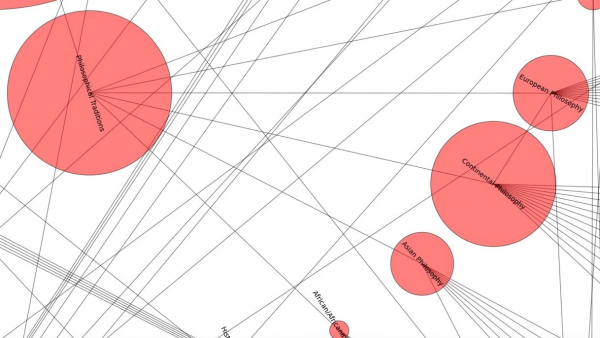

Everyone interested in philosophy must occasionally face the question of how, exactly, to define philosophy itself. You can always label as philosophy whatever philosophers do — but what, exactly, do philosophers do? Here the English comedians John Cleese of Monty Python and Jonathan Miller of Beyond the Fringe offer an interpretation of the life of modern philosophers in the form of a five-minute sketch set in “a senior common room somewhere in Oxford (or Cambridge).”

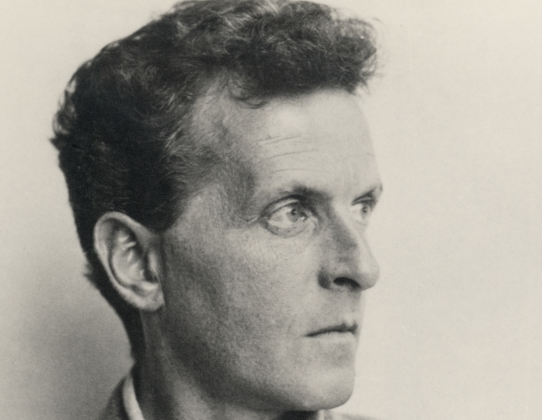

There, Cleese and Miller’s philosophers have a wide-ranging talk about Ludwig Wittgenstein, senses of the word “yes,” whether an “unfetched slab” can be said to exist, and the very role of the philosopher in this “heterogeneous, confusing, and confused jumble of political, social, and economic relations we call society.” They come to the tentative conclusion that, just as others drive buses or chop down trees, philosophers “play language games” — or perhaps “games at language” — “in order to find out what game it is that we are playing.”

As intentionally ridiculous as that explanation may sound, it wouldn’t come across as especially outlandish in many philosophy-department common rooms today. Cleese and Miller, no strangers to playing their own kinds of language games, get laughs not so much from mocking the nonsensical complexities of philosophy — and indeed, most of their lines make perfect sense on one level or another — as they do from so vividly expressing the distinctive manner of the “Oxbridge Philosopher” characters they portray. It has everything to do with manner, both verbal and physical, taken to as absurd an extreme as their lines of thinking.

Cleese and Miller’s version of the Oxbridge Philosopher sketch here comes from the 1977 Amnesty International benefit show and television special An Evening Without Sir Bernard Miles (also known as The Mermaid Frolics), but others exist. It goes at least as far back as Beyond the Fringe’s days pioneering their hugely influential brand of British satire on the stage in the 1960s; their earlier performance just above features Miller and fellow troupe member Alan Bennett. It can still make us laugh today, but we might well wonder whether anyone in the history of humanity has ever really sounded like this — in which case, we should watch footage of real-life Oxford philosophers back in those days and judge for ourselves.

Related Content:

Atheism: A Rough History of Disbelief, with Jonathan Miller

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.