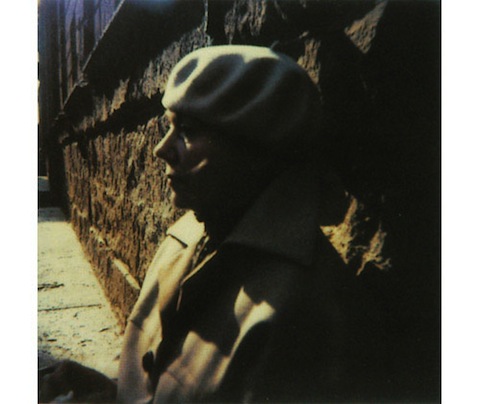

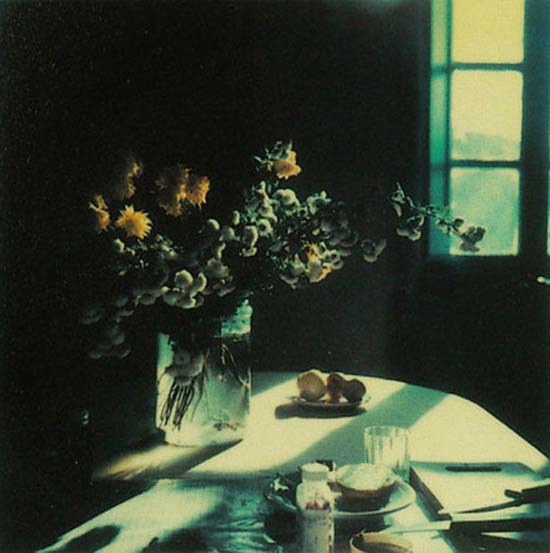

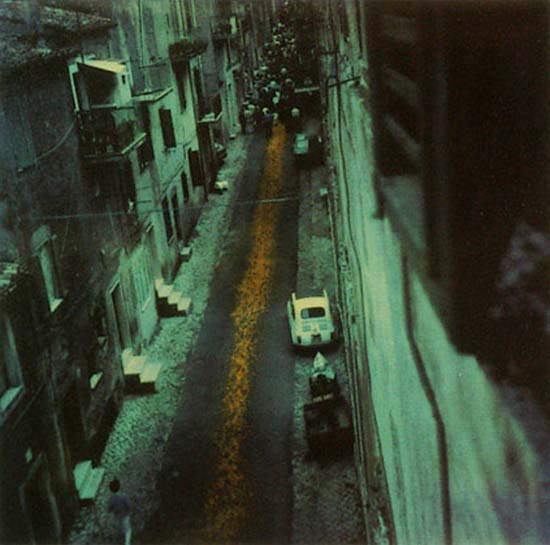

The Google Cultural Institute has drawn our attention before, with its virtual exhibitions on the rise of the Eiffel Tower, the fall of the Iron Curtain, and many other notable chapters of human history. Today, take a look at a Google Cultural Institute gallery that has a foot in literature as well as in history, Dubliners: the Photographs of J.J. Clarke from the National Library of Ireland. Subtitled “a glimpse of James Joyce’s Dublin,” the online show presents pictures taken by this fellow Clarke at the turn of the 20th century, when he came to the Irish capital to study medicine. His “photojournalistic approach to his subjects allowed him to capture vivid scenes from the daily lives of Dublin’s men, women and children.”

This made Clarke a contemporary of Joyce, and so his “images also show us how the city looked” to the writer “whose best known works — the short story collection Dubliners, and the novels A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses — are all set around that time, when Joyce too was a young student fascinated by the world around him.”

Both the photographer and the novelist, in their separate forms, set about capturing the city, the era, and the culture around them, and the pictures of Clarke’s featured at the Google Cultural Institute could easily illustrate any of Joyce’s books.

I’ve long enjoyed repeating the observation that, had the real Dublin crumbled, we could rebuild it from the details given in Ulysses — or at least we could rebuild the Dublin of 1904. But I now accept that having on hand Clarke’s photographs, about which you can learn much more at the National Library of Ireland’s site, they would greatly speed the reconstruction process as well. All of the Joycean texts mentioned above can be found in our collection of Free Audio Books and Free eBooks.

Related Content:

Vladimir Nabokov Creates a Hand-Drawn Map of James Joyce’s Ulysses

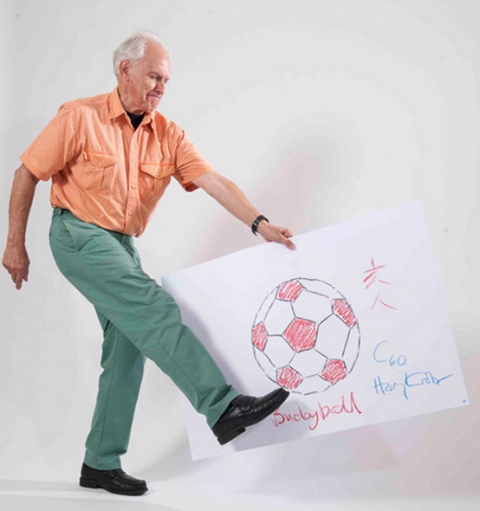

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

James Joyce Reads ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’ from Finnegans Wake

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.