For every august personage who’s taken a crack Edgar Allan Poe’s evergreen poem, “The Raven,” there are thousands more who haven’t.

Humorist Jordan Monsell is doing what he can to close that gap, providing a sampling of 100 mostly male, mostly white, mostly human celebrity voices. It’s a solo recitation, but vocally a collaborative one, with a fair number of animated characters making their way into the credits, too.

He certainly knows how to cast outside the box. Traditional Poe interpreters such as Vincent Price and John Astin bring some well established creep cred to the enterprise. Monsell picks Christopher Walken and Christopher Lee already have existing takes on this classic, and Anthony Hopkins and Willem Dafoe are welcome additions.

But what to make of Jerry Seinfeld, Pee-Wee Herman, Johnny Cash… and even poetry lover Bill Murray? Manic and much missed Robin Williams may offer a clue. What good is having an arsenal of impressions if you’re not willing to roll them out in rapid succession?

While some of Monsell’s impersonations (cough, David Bowie) fall a bit short of the mark, others will have you regretting that no one had the forethought to record Don Knotts or JFK reciting the poem in its entirety.

The titles offer a bit of a misnomer. In many instances, it’s not really the performers but their best known characters being aped. While there may not be too great a vocal divide between playwright Wallace Shawn and Vizzini in The Princess Bride, The Dude is not Jeff Bridges, any more than Captain Jack Sparrow is Johnny Depp.

The project seems likely to play best with nerdy adolescent boys… which could be good news for teachers looking to get reluctant readers onboard. Show it on the classroom Smart Board, and be prepared to have mini-teach-ins on Katharine Hepburn, Walter Matthau, the late great Robert Shaw, and other big names whose day has passed. Shrek, Gollum, and Harry Potter’s house elf, Dobby, are on hand to keep the references from feeling too moldy.

The specter of Poe gets the coveted final word, a balm to the ears after the triple assault of Christian Bale’s Batman, Mad Max’s Tom Hardy, and Heath Ledger’s Joker. (It may be a matter of taste. You’ll hear no complaint from these quarters with regard to Mickey Mouse, Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion, or The Simpson’s Krusty the Klown, wonderfully unctuous.)

The breakneck audio patchwork approach doesn’t do much for reading comprehension, but could lead to a lively middle school discussion on what constitutes a successful performance. Who served the text best? Readers?

Furthermore, who’s missing? What voice would you add to the Monsell’s roll call, below?

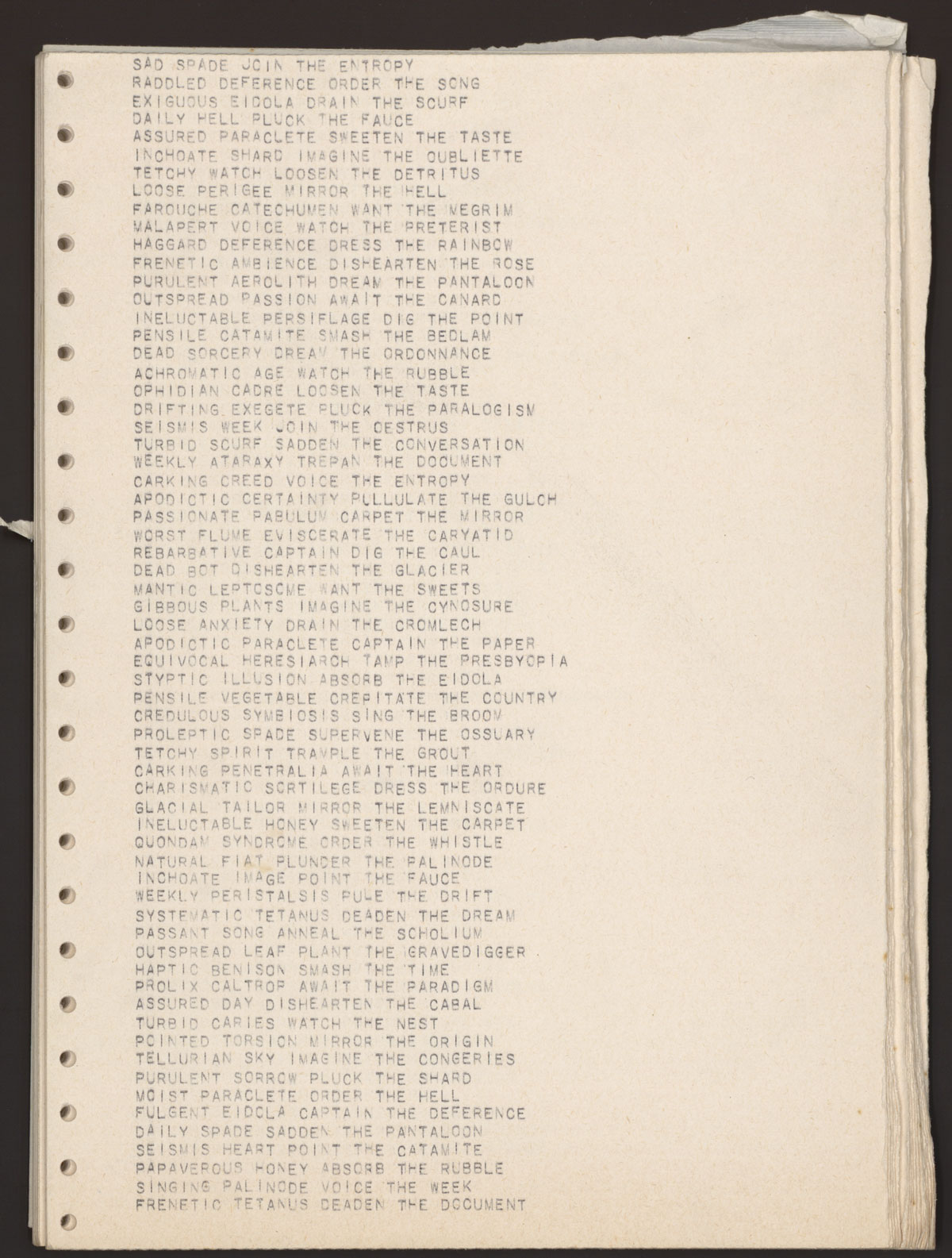

Morgan Freeman

Kermit the Frog

Johnny Cash

Ringo Starr

David Bowie

Rick Moranis

Gary Oldman

Peter Lorre

Adam Sandler

Don Knotts

William Shatner

George Takei

Michael Dorn

Daffy Duck

Ricky Gervais

Foghorn Leghorn

Liam Neeson

Nicholas Cage

John Travolta

Anthony Hopkins

Rod Serling

Cookie Monster

Jay Baruchel

Jeff Bridges

Johnny Depp

Archer

Dr. Phil

Gollum

Mandy Patinkin

Wallace Shawn

Billy Crystal

Owen Wilson

Dustin Hoffman

Krusty the Klown

Apu

Christian Bale

Michael Caine

Tom Hardy

Heath Ledger

Mickey Mouse

John Wayne

Jerry Seinfeld

Phil Hartman

Goofy

Al Pacino

Marlon Brando

Jack Lemmon

Walter Matthau

Christopher Walken

Rowlf the Dog

John Cleese

Robin Williams

Katharine Hepburn

Woody Allen

Matthew McConaughey

Cowardly Lion

Jimmy Stewart

John C. Reilly

James Mason

Sylvester Stallone

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Stewie

Daniel Day Lewis

Maggie Smith

Alan Rickman

Dobby

Jack Nicholson

Christoph Waltz

Bill Murray

Dan Aykroyd

Sean Connery

Bill Cosby

Christopher Lloyd

Droopy Dog

Kevin Spacey

Harrison Ford

Ronald Reagan

JFK

Bill Clinton

Keanu Reeves

Ian McKellen

Paul Giamatti

Sebastian

Stan Lee

Jeff Goldblum

Hugh Grant

Kenneth Branagh

Larry the Cable Guy

Pee-Wee Herman

Shrek

Donkey

Charlton Heston

Michael Keaton

Homer Simpson

Yoda

Willem Dafoe

Bruce Willis

Robert Shaw

Christopher Lee

Edgar Allan Poe

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.