Literature and film can open up to the depth and immensity of social truths we find profoundly difficult, if not impossible, to articulate. If our political vocabulary (as Oxford Dictionaries suggested in their word of the year) has become “post-truth,” it can seem like the only honest representations of reality are found in the imaginary.

Amidst the violent upheavals of the last couple decades, for example, we have seen an explosion of the dystopian, that venerable yet modern genre we use to explain our contemporary political conditions to ourselves. It has become common practice in serious debate to gesture toward the outsized cinematic scenarios of Snowpiercer, or The Hunger Games and Harry Potter series, as stand-ins for disturbing present realities.

You may have also encountered recent references to literary speculative fiction like William Gibson’s The Peripheral, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Olivia Butler’s Parable series, and Philip K. Dick’s Radio Free Albemuth, the first novel Dick wrote before VALIS about his supposed religious experience. Drafted in 1976 but only published posthumously in 1985, Dick’s prescient novel takes place in an alternate U.S. (like The Man in the High Castle), in which paranoid right-wing zealot Ferris Fremont, a Joseph McCarthy/Richard Nixon-like figure, succeeds Lyndon Johnson as president.

There is no point in dwelling on the ethics of Ferris Fremont.… The Soviets backed him, the right-wingers backed him, and finally just about everyone… Fremont had the backing of the US intelligence community, as they liked to call themselves, and exigents played an effective role in decimating political opposition. In a one-party system there is always a landslide.

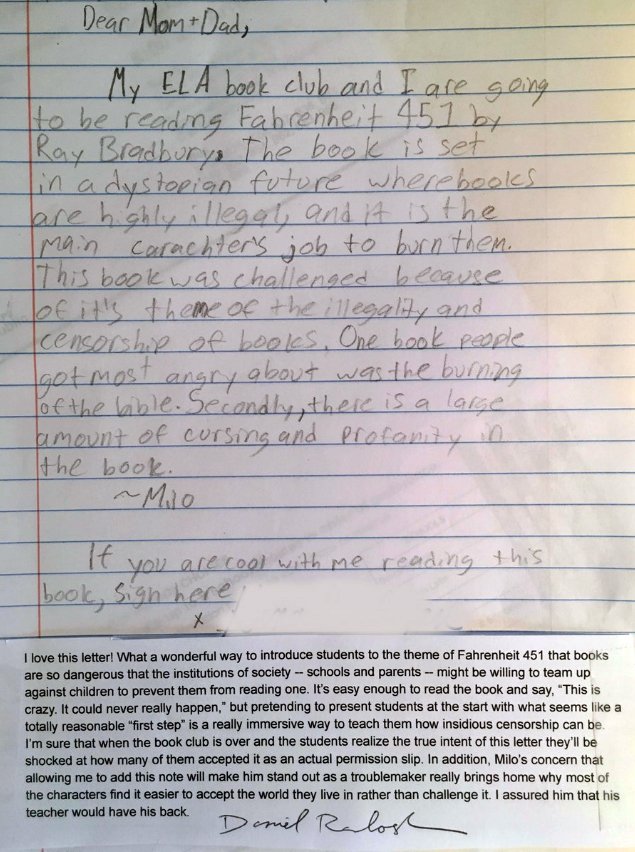

The stifling totalitarian control Fremont exercises is very much a hallmark of dystopian fiction. But does Dick’s novel—set in an alternate present rather than a frightening future, and with an alien/supernatural invasion—qualify as dystopian? What about Harry Potter, with its fairy tale intrusions of the magical into the present? The TED Ed video at the top, narrated by Alex Gendler, sets flexible boundaries for a category we’ve mostly come to associate with prophetic, futuristic science fiction, and offers a broadly comprehensive definition.

The word dystopia, a Greek coinage for “bad place,” dates to 1868, from a usage by John Stuart Mill to characterize the industrial world’s moral inversion of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia. That word, Gendler points out, is a term More invented to mean either “no place” or “good place.” Gendler dates the emergence of the dystopian to Jonathan Swift’s satire Gulliver’s Travels, a book, like Harry Potter, set in an alternate present featuring many monstrous intrusions of the fantastic into the real. Unlike the boy wizard’s saga, however, the monsters in Gulliver serve as allegories for us.

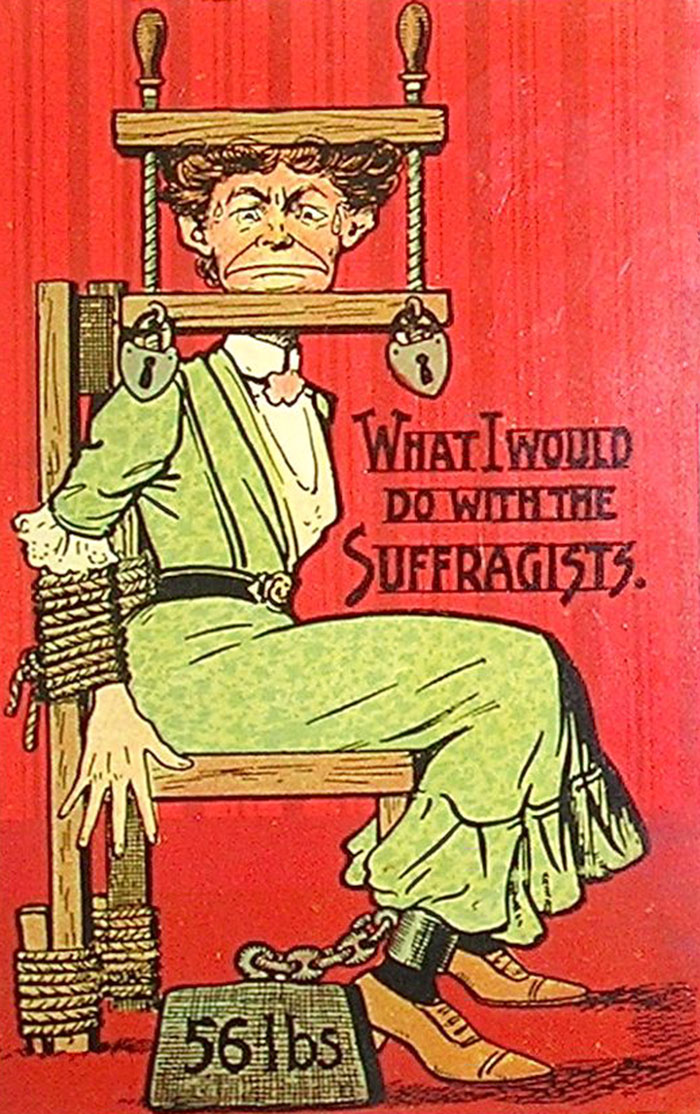

Swift, Gendler argues, “established a blueprint for dystopia.” His Lilliputians, Bobdingnagians, Laputions, and Houyhnhnms all represent “certain trends in contemporary society… taken to extremes.” In later examples, the form continued to reflect the pernicious thought and science of the age: the extreme eugenics of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, the prison-like factory conditions of Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis, the repressive hyper-rationalization in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1924 Soviet-based dystopia We, and the medical technocracy of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

Borrowing liberally from Zamyatin and competing with Huxley, George Orwell’s 1984 set a new standard of verisimilitude for dystopian fiction, starkly reminding thousands of post-war readers that “the best-known dystopias were not imaginary at all,” Gendler says. The historical nightmares of World War II and the following Cold War dictatorships birthed horrors for which we can never find appropriate language. And so we turn to novels like 1984 and Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, both of which aptly show us worlds where language has ceased to function in any ordinary communicative sense.

Perhaps one of the most-referenced of dystopian novels in U.S. political discourse, Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 It Can’t Happen Here, gave little but its title to the popular lexicon. “Lewis,” writes Alexander Nazaryan in The New Yorker, “was never much of an artist, but what he lacked in style he made up for with social observation.” The novel “envisioned how easily,” Gendler says, “democracy gives way to fascism.” The crisis point comes when the people want “safety and conservatism again,” as Roosevelt observed that same year—a year in which “the promise of the New Deal,” Nazaryan remarks, “remained unfulfilled for many.”

The irony of Lewis’ scenario is that those left behind by Roosevelt’s policies are those who suffer most under the fictional presidency of authoritarian Senator Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip. Meanwhile, the more comfortable console themselves with hollow denials: “it can’t happen here.” Extreme economic inequality and social stratification have been an essential feature of classical utopian fiction since its first appearance in Plato’s Republic. In the modern literary dystopia, the science, technology, and political mechanization that philosophers once celebrated become implacable weapons of war against the citizenry.

For all the malleable boundaries of the genre—which strays into science fiction, fantasy, surrealism, and satire—dystopian fictions all have one unifying theme: “At their heart,” says Gendler, “dystopias are cautionary tales, not about some particular government or technology, but the very idea that humanity can be molded into an ideal shape.”

Related Content:

Huxley to Orwell: My Hellish Vision of the Future is Better Than Yours (1949)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness