Peter Capaldi is best known in the States for being the most recent actor to play Doctor Who. But did you know that he is also an Oscar-winning filmmaker? His brilliant short film Franz Kafka’s It’s a Wonderful Life took the prize for Best Short Film in 1995.

The movie shows Kafka, on Christmas Eve, struggling to come up with the opening line for his most famous work, The Metamorphosis.

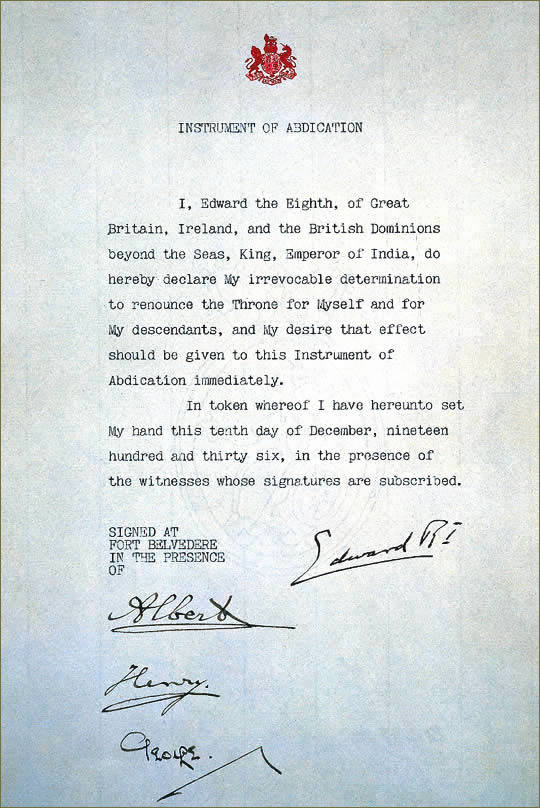

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.

Capaldi wrings a lot of laughs out of Kafka’s inability to figure out what Samsa should turn into. A giant banana? A kangaroo? Even when the answer is literally staring at him in the face, Kafka is hilariously obtuse.

Richard E. Grant stars as the tortured, tightly-wound writer who is driven into fits as his creative process is interrupted for increasingly absurd reasons. The noisy party downstairs, it turns out, is populated by a dozen beautiful maidens in white. A lost delivery woman offers Kafka a balloon animal. A local lunatic searches for his companion named Jiminy Cockroach.

You can see the film above, helpfully subtitled in German. Also find it in our collection 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More, plus our list of 33 Free Oscar Winning Films Available on the Web.

Related Content:

Find Works by Kafka in our lists of Free Audio Books and Free eBooks

Watch Franz Kafka, the Wonderful Animated Film by Piotr Dumala

The Art of Franz Kafka: Drawings from 1907–1917

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.