Click the image to view larger version

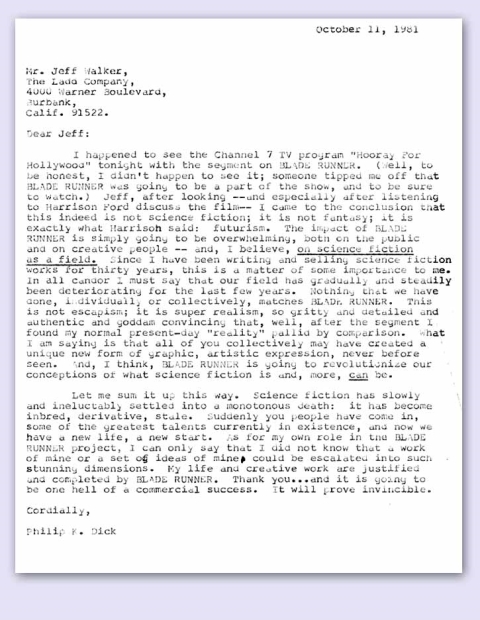

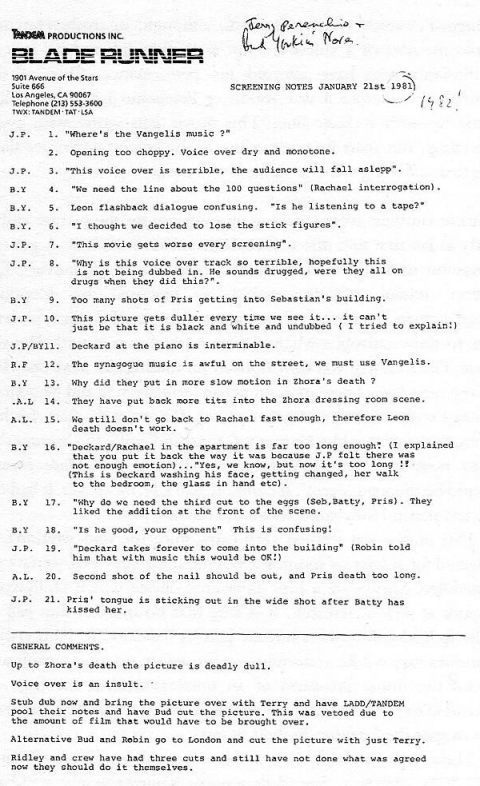

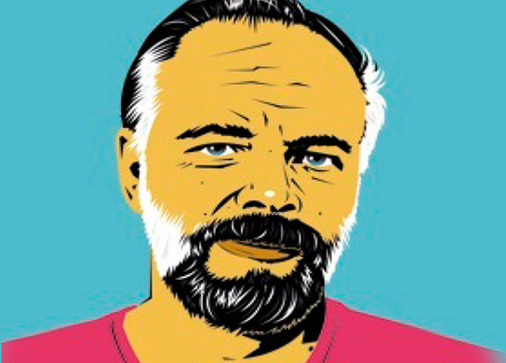

Last week we featured studio-executive notes on Blade Runner. “This movie gets worse every screening,” they said. “Deadly dull,” they said. “More tits,” they said. These remarks now offer something in the way of irony and entertainment, but they only give even the most avid Blade Runner enthusiast so much to think about. For a more interesting reaction, and certainly a more articulate one, we should turn to Philip K. Dick, the prolific writer of psychologically inventive science fiction whose Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? provided Blade Runner’s source material. Dick, alas, would not live to see the film open in theaters, much less ascend to the top of the canon of sci-fi cinema decades later, but he did get a good look, before moving on to other realms, at the script and some of the footage. With just those, he managed to outguess everyone — audiences, critics, and especially studio executives — about the film’s fate.

“This indeed is not science fiction,” Dick wrote in a letter available on his official site. “It is not fantasy; it is exactly what [star] Harrison [Ford] said: futurism. The impact of Blade Runner is simply going to be overwhelming, both on the public and on creative people — and, I believe, on science fiction as a field. [ … ] Nothing we have done, individually or collectively, matches Blade Runner. This is not escapism; it is super realism, so gritty and detailed and authentic and goddam convincing that, well, after the segment I found my normal present-day ‘reality’ pallid by comparison.” 32 years on, many of us frequent Blade Runner-watchers feel just the same way, and Dick wrote that after catching nothing more than a segment about the picture on the news. “It was my own interior world,” he later told interview John Boonstra. “They caught it perfectly.” And, at this point, all of our interior worlds look a little more Blade Runner-esque.

H/T to Marianne for the lead on the PKD letter.

Related Content:

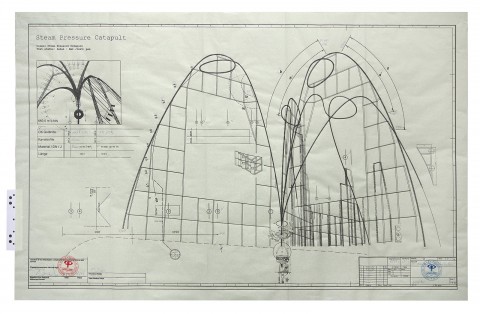

The Blade Runner Sketchbook: The Original Art of Syd Mead and Ridley Scott Online

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.