Maybe it’s the cloistered headiness of Rene Descartes, or the rigorous austerity of Isaac Newton; maybe it’s all the leathern breaches, gray waistcoats, sallow faces, and powdered wigs… but we tend not to associate Enlightenment Europe with an explosion of color theory. Yet, philosophers of the late 17th and 18th centuries were obsessed with light and sight. Descartes wrote a treatise on optics, as did Newton.

Newton first described in his 1672 Opticks the “revolutionary new theory of light and colour,” the University of Cambridge Whipple Library writes, “in which he claimed that experiments with prisms proved that white light was comprised of light of seven distinct colours.” Scientists debated Newton’s theory “well into the 19th century.”

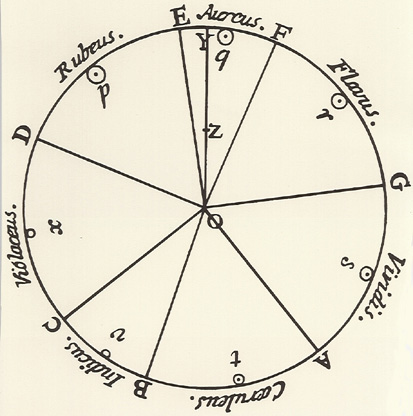

One early opponent famously illustrated his rebuttal. Poet, writer, and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published Theory of Colors (see here), with its carefully hand-drawn and colored diagrams and wheels, in 1809. From Newton’s time onward, color theorists elaborated prevailing concepts with color wheels, the first attributed to Newton in 1704 (and drawn in black and white, above).

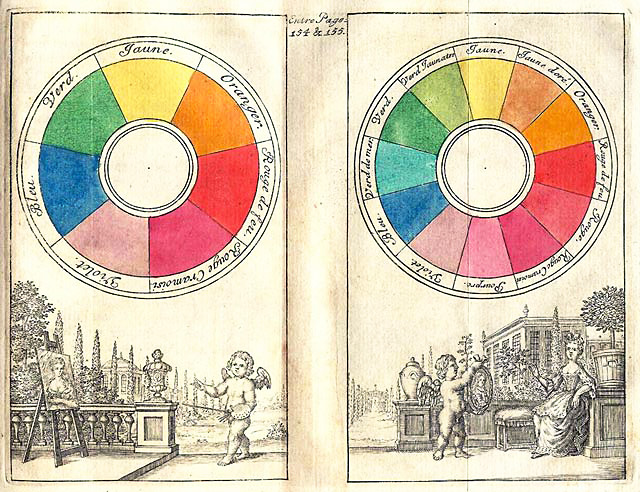

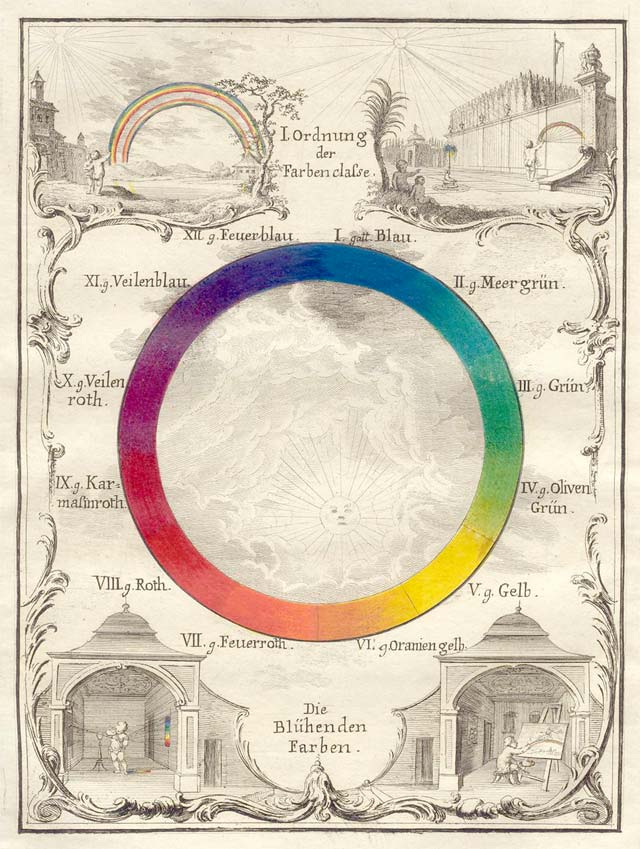

Newton’s wheel “arranged red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet into a natural progression on a rotating disk.” Four years later, painter Claude Boutet made his 7‑color and 12-color circles (top), based on Newton’s theories. Artists, chemists, mapmakers, poets, even entomologists… everyone seemed to have a pet theory of color, generally accompanied by elaborate colored charts and diagrams.

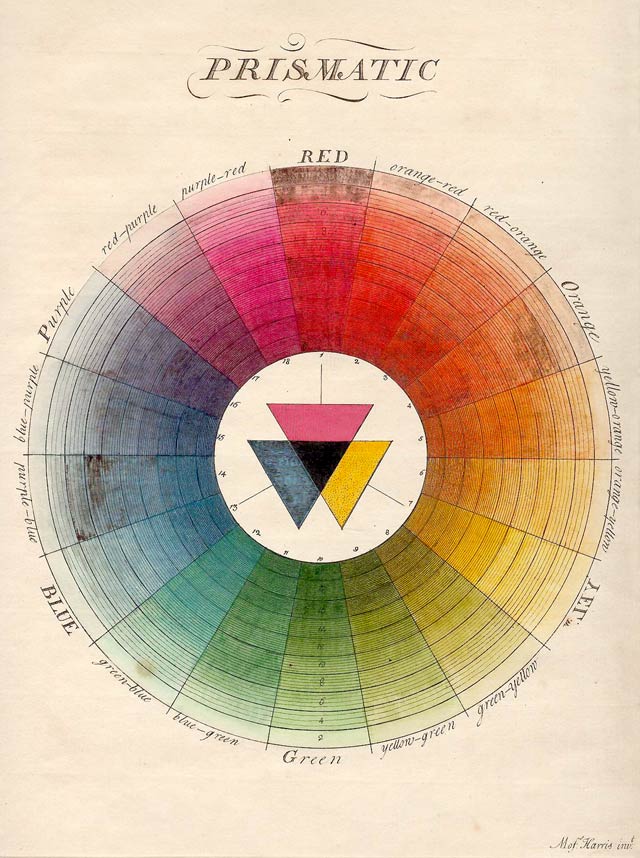

The color wheel was one among many forms—which often presented contrasting theories, like that of Jacques-Fabien Gautier, who argued that black and white were primary colors. But the wheel, and Newton’s basic ideas about it, have endured almost unchanged. The wheel further up (third one from top) by British entomologist Moses Harris from 1776 shows Newton’s 7‑color scheme simplified to the 6 primary and secondary colors we usually see, arranged in the complementary and analogous scheme, with tertiary gradations between them. Another entomologist, Ignaz Schiffermüller, drew the 12-color wheel right above.

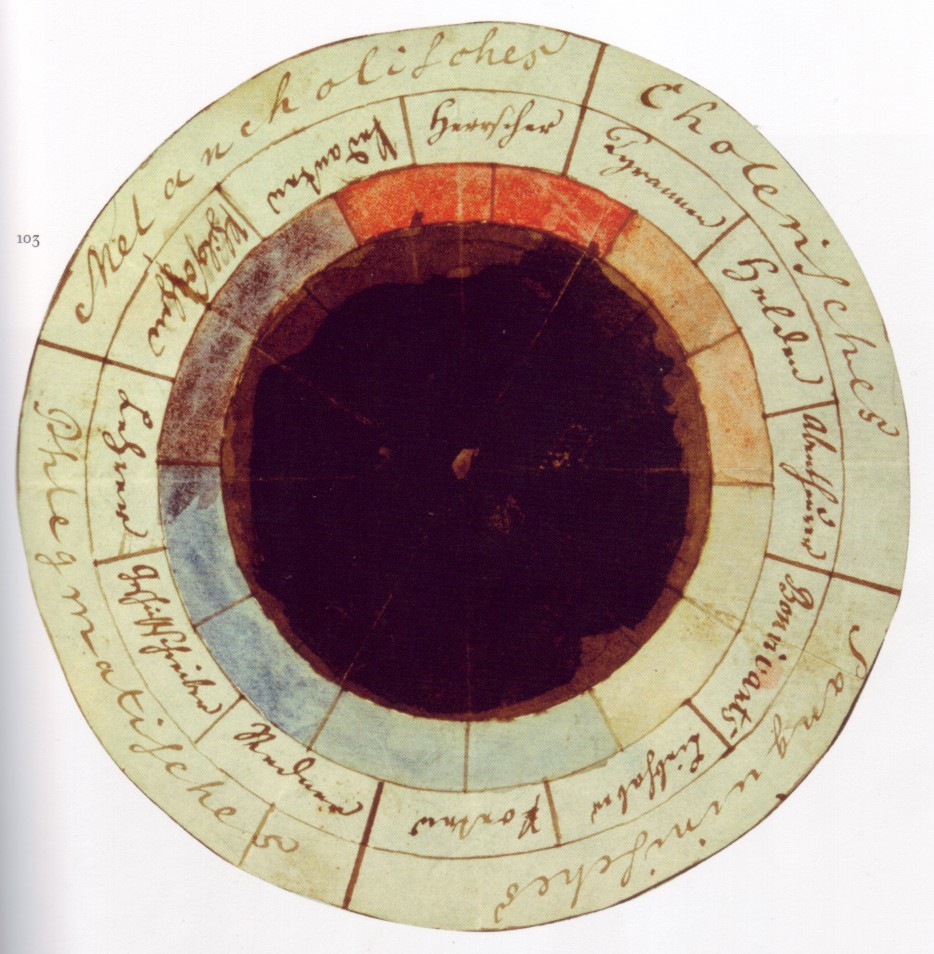

Color is always representative. Newton’s original wheel included “musical notes correlated with color.” By the end of the 18th century, color theory had become increasingly tied to psychological theories and typologies, as in the wheel above, the “rose of temperaments,” made by Goethe and Friedrich Schiller in 1789 to illustrate “human occupations and character traits,” the Public Domain Review notes, including “tyrants, heroes, adventurers, hedonists, lovers, poets, public speakers, historians, teachers, philosophers, pedants, rulers,” grouped into the four temperaments of humoral theory.

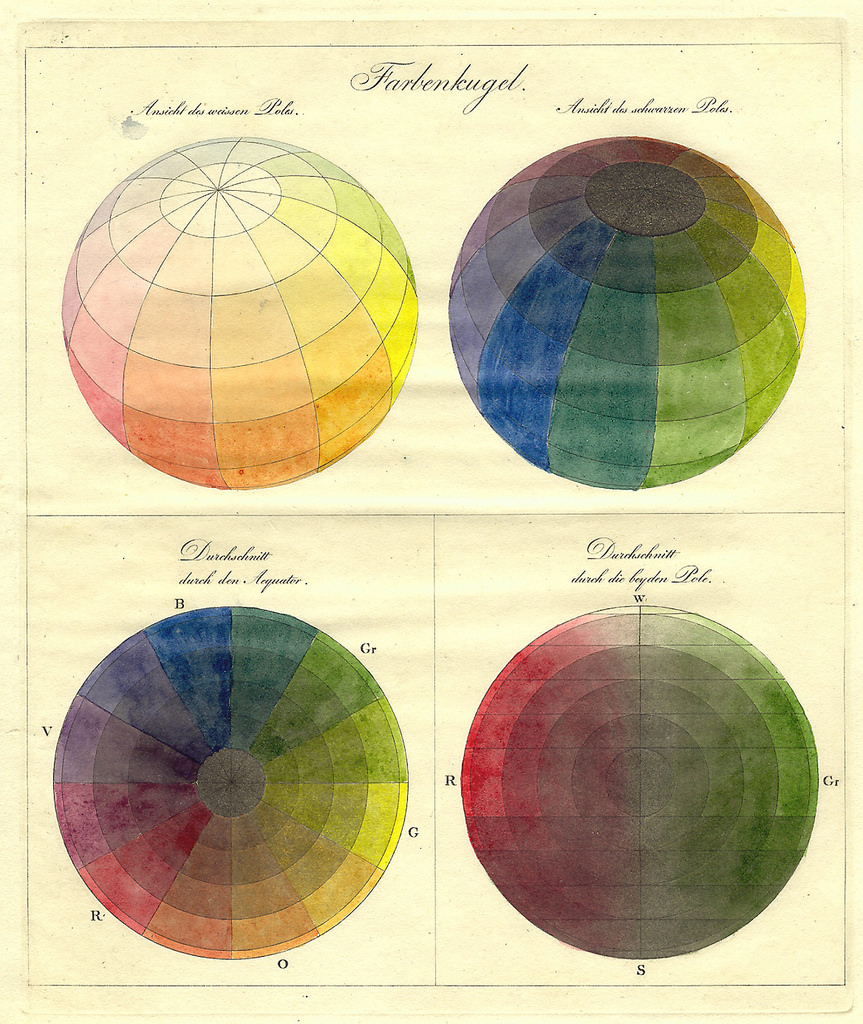

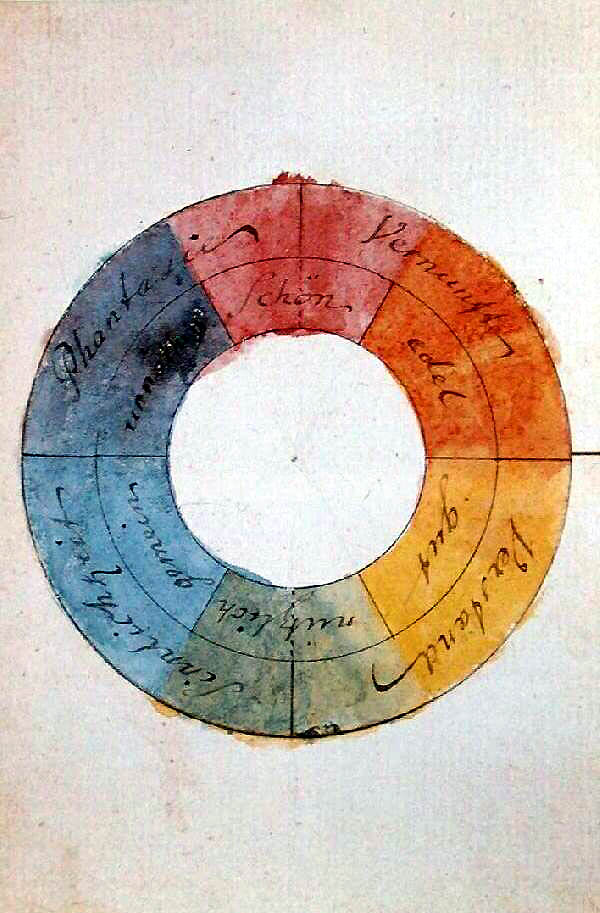

It’s a fairly short leap from these psychologies of color to those used by advertisers and commercial designers in the 20th century—or from the artists and scientists’ color theories to abstract expressionism, the Bauhaus school, and the chemists and photographers who recreated the colors of the world on film. (Goethe’s color wheel, below, from Theory of Color, illustrates his chapter on “Allegorical, symbolic, and mystical use of colour.”) See more early color wheels, like Philipp Otto Runge’s 1810 Farbenkugel, as well as other conceptual color schemes, at the Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

A Pre-Pantone Guide to Colors: Dutch Book From 1692 Documents Every Color Under the Sun

Sir Isaac Newton’s Papers & Annotated Principia Go Digital

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness