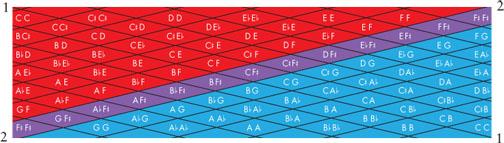

Before Pantone invented “a universal color language” or big box hardware stores arose with proprietary displays of colorfully-named paints—over a century before, in fact—a German mineralogist named Abraham Gottlob Werner invented a color system, as detailed and thorough a guide as an artist might need. But rather than only cater to the needs of painters, designers, and manufacturers, Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours also served the needs of scientists. “Charles Darwin even used the guide,” writes This is Colossal, “during his voyage to the Madeira, Canary, and Cape Verde islands on the H.M.S. Beagle.”

Werner’s is one of many such “color dictionaries” from the 19th century, “designed to give people around the world a common vocabulary,” writes Daniel Lewis at Smithsonian, “to describe the colors of everything from rocks and flowers to stars, birds, and postage stamps.” These guides appealed especially to naturalists.

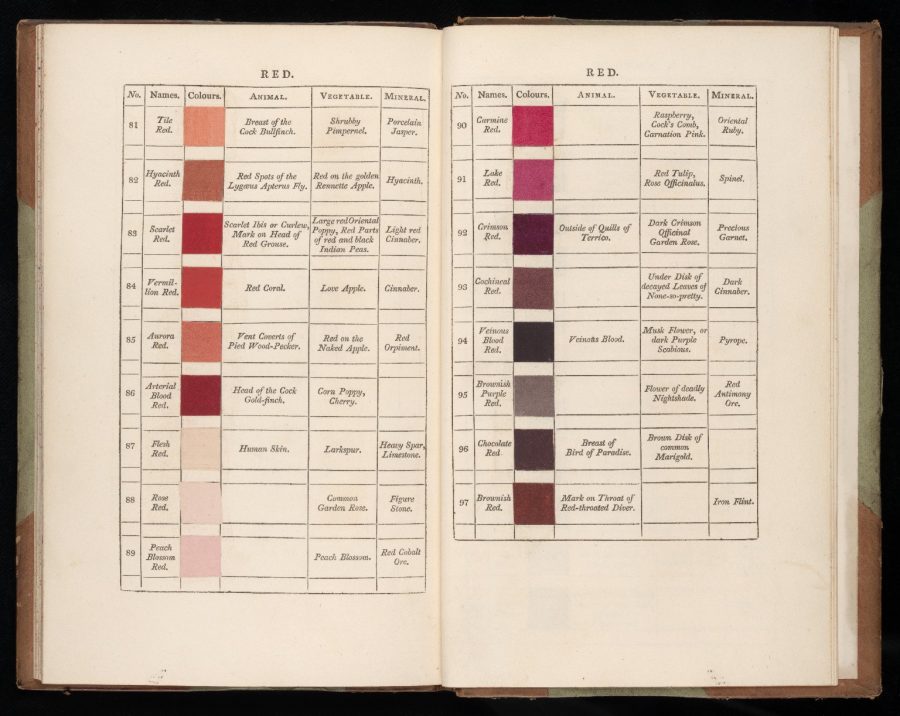

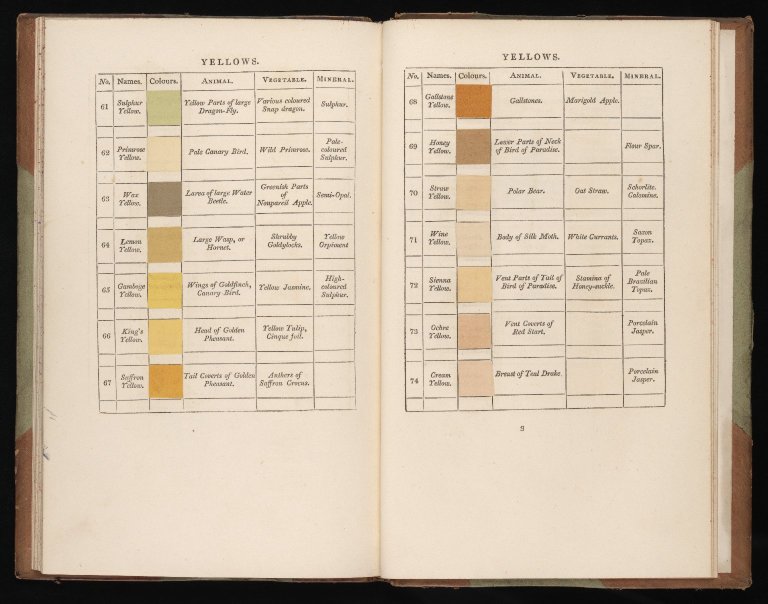

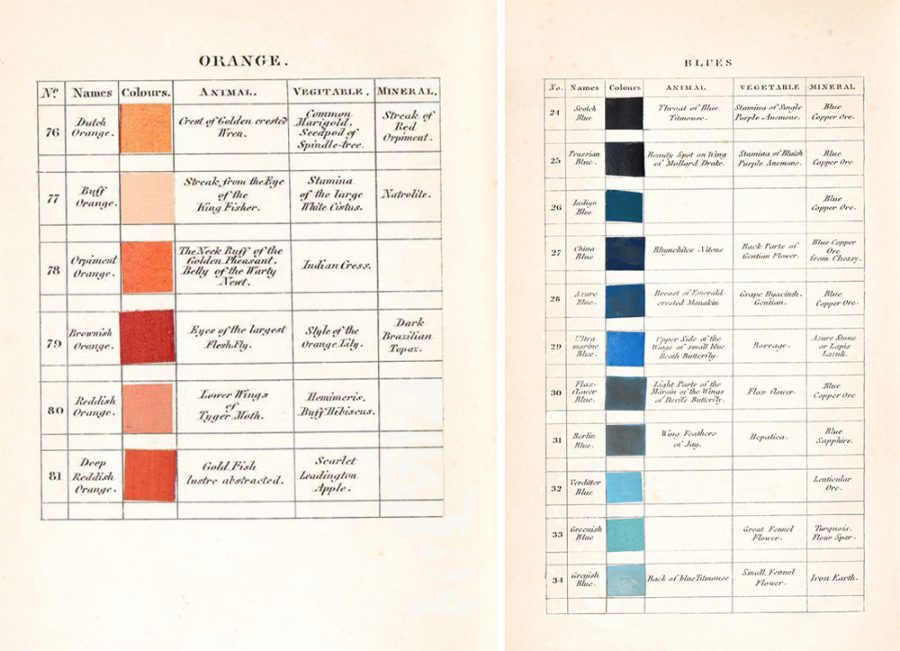

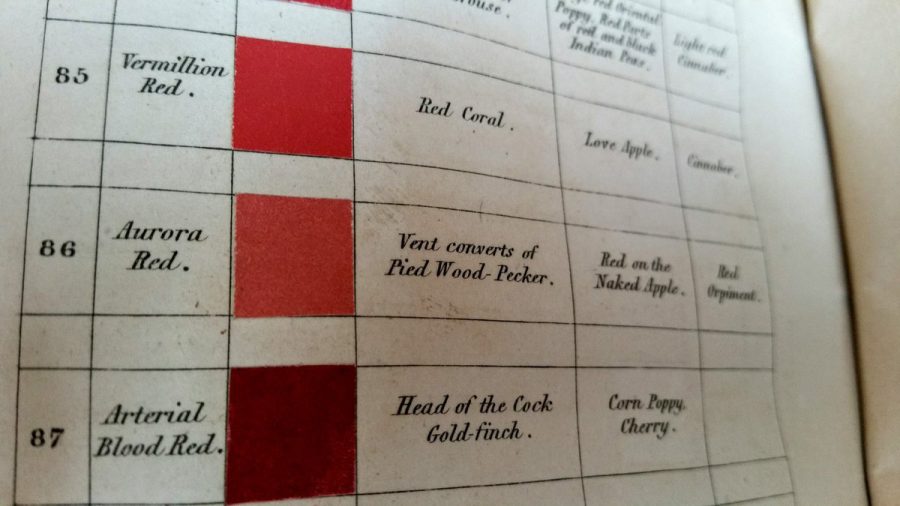

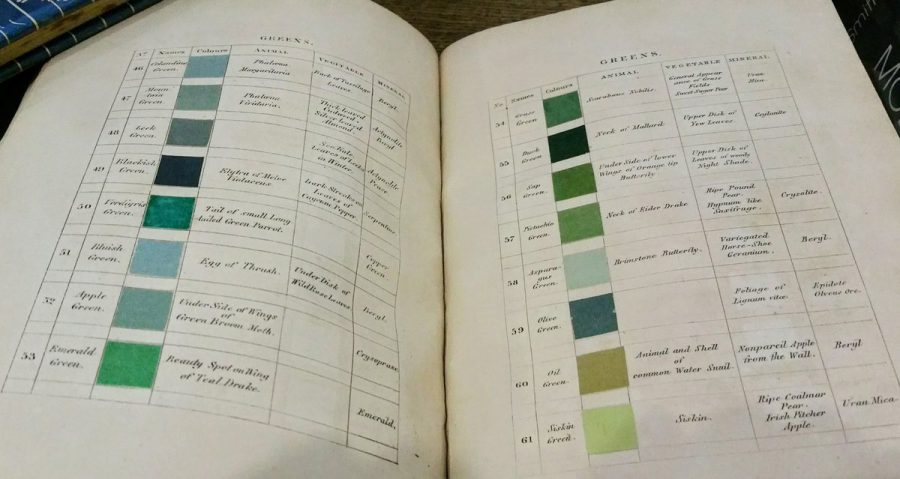

Indeed, the book began—before Scottish painter Patrick Syme updated the system in English, with swatches of example colors—as a naturalist’s guide to the colors of the world, naming them according to Werner’s poetic fancy. “Without an image for reference,” the original text “provided immense handwritten detail describing where each specific shade could be found on an animal, plant, or mineral. Many of Werner’s unique color names still exist in common usage, though they’ve detached from his scheme ages ago.

Prussian Blue, for instance, which can be located “in the beauty spot of a mallard’s wing, on the stamina of a bluish-purple anemone, or in a piece of blue copper ore.” Other examples, notes Fast Company’s Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan, include “’Skimmed Milk White,’” or no. 7… found in ‘the white of the human eye’ or in opals,” and no. 67, or “’Wax Yellow’… found in the larvae of large Water Beetles or the greenish parts of a Nonpareil Apple.” It would have been Syme’s 1814 guide that Darwin consulted, as did scientists, naturalists, and artists for two centuries afterward, either as a taxonomic color reference or as an admirable historic artifact—a painstaking description of the colors of the world, or those encountered by two 18th and 19th century European observers, in an era before photographic reproduction created its own set of standards.

The book is now being republished in an affordable pocket-size edition by Smithsonian Books, who note that the Edinburgh flower painter Syme, in his illustrations of Werner’s nomenclature, “used the actual minerals described by Werner to create the color charts.” This degree of fidelity to the source extends to Syme’s use of tables to neatly organize Werner’s precise descriptions. Next to each color’s number, name, and swatch, are columns with its location on various animals, vegetables and minerals. “Orpiment Orange,” named after a mineral, though none is listed in its column, will be found, Werner tells us, on the “neck ruff of the golden pheasant” or “belly of the warty newt.” Should you have trouble tracking these down, surely you’ve got some “Indian cress” around?

While its references may not be those your typical industrial designer or graphic artist is likely to find helpful, Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours will still find a treasured place in the collections of designers and visual artists of all kinds, as well as historians, writers, poets, and the scientific inheritors of 19th century naturalism, as a “charming artifact from the golden age of natural history and global exploration.” Flip through a scanned version of the 1821 second edition just above, including Werner’s introduction and careful lists of color properties, or read it in a larger format at the Internet Archive. The new edition is now available for purchase here.

Related Content:

The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665–1810)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness